Fanny and Alexander

1982

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The spiritual legacy of a great man of cinema: a majestic, lyrical, and revolutionary work. It is the dazzling epilogue to a titanic career, not just a film, but an entire cosmogony encapsulated in frames, a sumptuous farewell to the big screen that Bergman, though later returning to direct for television, imagined as his definitive artistic testament. A work that, while announcing a goodbye, resonates with the vitality of a rebirth, a profound journey into the labyrinth of memory and fantasy.

Distributed in two versions, one of 190 minutes, the other of 312, more aligned with Bergman's vision, who wished to present to the public a family saga à la Mann. This ambition, to build an imposing and detailed narrative cathedral, is fully realized in the extended version, originally conceived as a television mini-series for SVT. It is precisely in this monumental form that Bergman's tableau unfolds its almost novelistic richness, offering the audience not just a story, but an entire universe of characters, relationships, and micro-dramas that unfold with the sumptuous slowness and psychological penetration typical of great nineteenth-century novels. The comparison with Thomas Mann is not accidental: like the Buddenbrooks, the Ekdahls are a bourgeois family, but their bourgeoisie is infused with a bohemian exuberance, an innate theatricality that splendidly contrasts with the sobriety and Lutheran rigidity of the era.

The story is precisely that of a family, the Ekdahls, in a Swedish city (Uppsala) at the beginning of the 20th century, specifically from 1903 to 1905. Bergman, with the meticulousness of a miniaturist and the vision of a fresco painter, reconstructs an era of transition, a turn of the century that pulsates with a life still rooted in tradition but already facing incipient modernism. The Ekdahl dwelling, with its warm lights and rooms teeming with life, resonates with laughter, music, and amateur theatricals, embodying a childlike Eden destined to be shaken by the violence of reality.

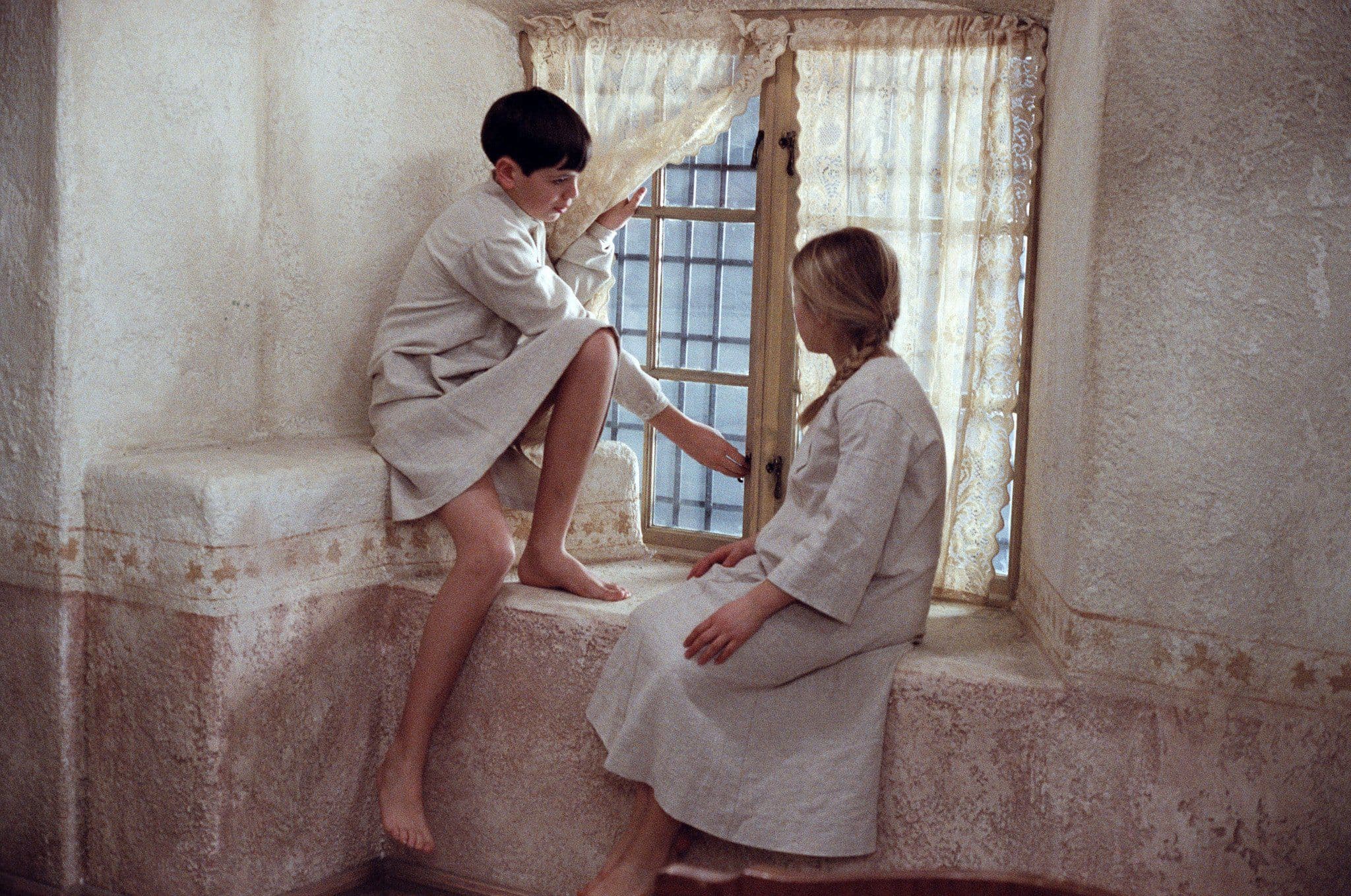

Fanny and Alexander are the exuberant children of Emilie, a woman who will soon lose her husband Oscar, director of the local theatre, and remarry the city's Lutheran bishop, Edvard Vergérus. Their transition from the warm, imaginative world of the Ekdahls to the austere, repressive one of the bishop is the film's beating and tragic heart. The world of the Ekdahls is a hymn to life, to creativity, to the joy of the senses; a place where theatre is not only a profession but an existential philosophy, where the boundaries between reality and fiction, play and life, are fluid and permeable.

The children will immediately come into conflict with the man who will reduce them to miserable wretches. Bishop Vergérus is not merely an antagonist: he is the quintessence of moralistic and punitive authority, a figure Bergman, son of a Protestant pastor, knew all too well in its most oppressive nuances. His regime is one of cold discipline, deafening silences, of a dogmatic religiosity that suffocates every spark of imagination and autonomy. Alexander, in particular, with his fervent imagination and his irrepressible tendency to confuse truth and falsehood (or perhaps, to create his own truth), becomes Vergérus's favorite target, triggering a psychological battle for the survival of the spirit. The film thus transforms into a parable on the resilience of imagination and the power of narration as a tool for self-defense and liberation against all forms of oppression.

Surrounding this is Bergman's great mastery in reconstructing his beloved turn-of-the-century Sweden. This is not a simple historical reconstruction, but an evocation imbued with nostalgia and affection, filtered through the prism of childhood memory. Cinematographer Sven Nykvist and production designer Anna Asp weave a visual tapestry of extraordinary beauty, where every detail, from the sumptuous costumes to the warm lights that flood the family scenes, speaks of a lost and desired world. The Ekdahl home, a triumph of precious fabrics, carved furniture, and art objects, contrasts sharply with the geometric austerity and cold grayness of the bishop's house, almost a purgatory on earth. This visual dichotomy is key to understanding the spiritual and psychological battle the protagonists face.

And then: striking family contrasts, fairytale visions, religion, and magic as elements that dance and merge within the story. These themes are not merely juxtaposed, but intricately woven into a complex and fascinating narrative and visual fabric. The contrast between the chaotic, affectionate, and pagan Ekdahl clan and the rigid, Calvinist, and almost sadistic bishop's household is the dramatic core. In the midst of this struggle between Dionysian and Apollonian, between pulsating life and aseptic repression, Alexander's fairytale visions intervene, which are not simple escapes from reality, but powerful weapons of resistance. Alexander's lies, his dreamlike projections, the ghosts that populate his mind become a vital counter-narrative, a form of alternative truth that challenges the tyranny of imposed reality.

Religion, a recurring theme in Bergman's work and often a source of torment, manifests itself here in its most austere and punitive form through the bishop, but also finds a liberating and arcane counterpart in the figure of Isak Jacobi, the elderly Jewish merchant. His home, a labyrinth of exotic curiosities and magical objects, becomes a sanctuary of mystery and salvation, a place where magic – understood as a mystical force and esoteric knowledge – offers an escape from the nightmare. Isak, with his ancient wisdom and his ability to manipulate the "real," represents a less dogmatic spirituality, closer to the transcendent, where the supernatural is a natural extension of the human psyche and the universe. The scene with the strange Ismael, enigmatic and androgynous prisoner in Jacobi's house, elevates the film to heights of unease and mystery, suggesting the presence of forces that go far beyond human comprehension and imposed rationality.

A true iconographic testament from one of the greatest directors of all time. "Fanny and Alexander" is not only a compendium of Bergman's cherished themes – violated childhood, the relationship with God, the crisis of faith, the liberating power of art, family dynamics, and the complexity of the human psyche – but also a stylistic synthesis of his entire filmography. From the rawest naturalism to the most unrestrained lyricism, from psychological drama to the supernatural element, Bergman masterfully orchestrates a work that is simultaneously an intimate family drama and a grand existential epic. It is a melancholy yet triumphant farewell, a definitive work that seals Bergman's place not only as a master of cinema but as a profound explorer of the human soul and its infinite capacity to dream, resist, and create, even in the face of the deepest darkness. The film remains a beacon in the history of cinema, a gem that continues to shine with its own, eternal, and unique light.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...