Faust

1926

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Murnau reinterprets Goethe with a profound and deferential gaze, yet simultaneously aware of the immense spaces to be explored with the new expressive medium at his disposal: the cinematograph. The result is this evocative tableau, bolstered by a strong striking visual power and a grand scenic sensibility. Murnau essentially performed a defamiliarizing operation, filtering Goethe's dreamscape and imprinting it onto film, transforming the dramatic canvas into a universe of pure vision. This was not merely an adaptation, but a true translation of philosophical concepts and inner states of mind into cinematic grammar, making tangible the existential unease that permeated Weimar Republic Germany. The result captivated and bewildered European audiences, consecrating the German director as a prophet of the new expressionism, a movement of which Faust became not only a visual cornerstone but also its most sumptuous metaphysical expression.

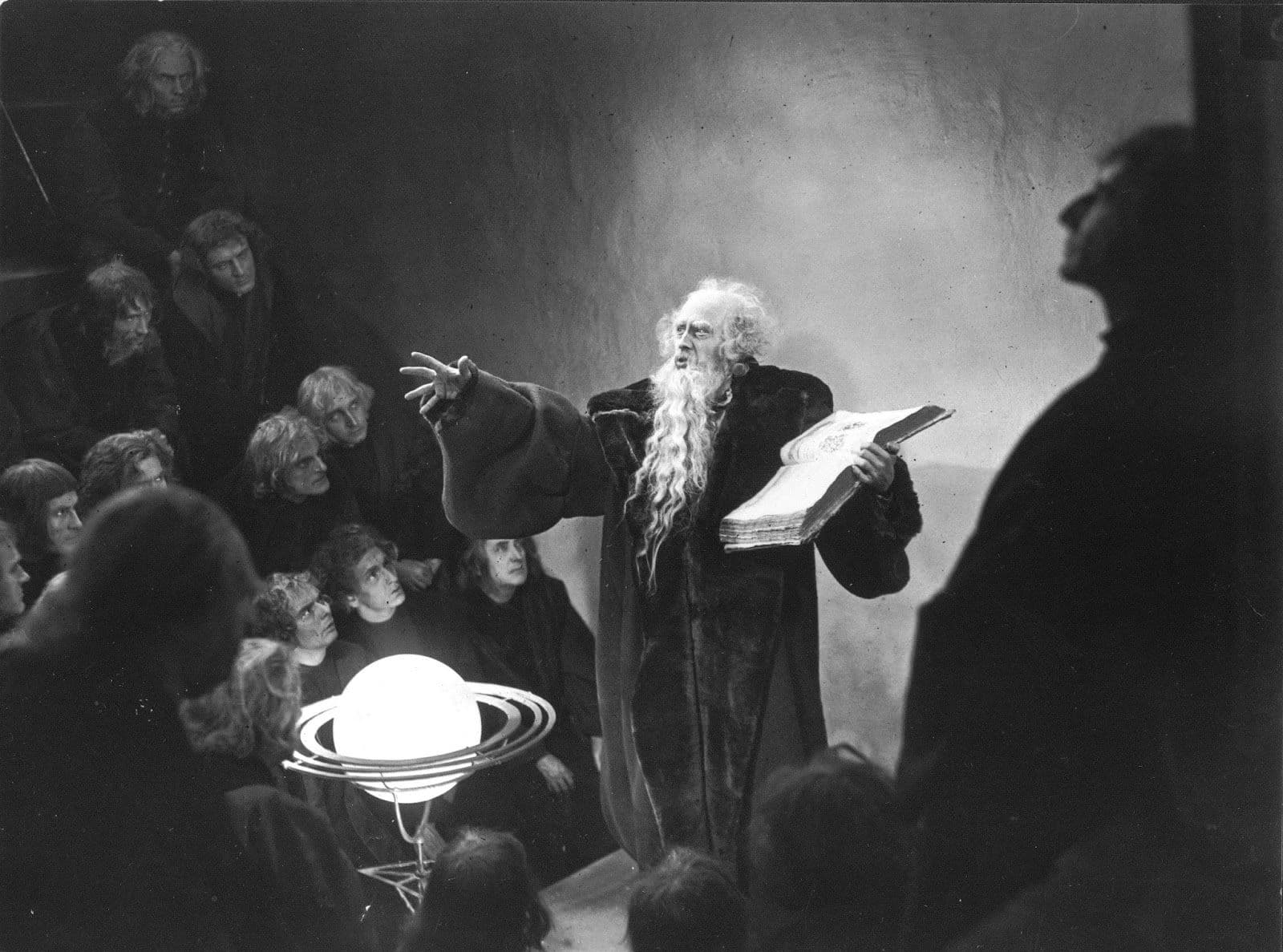

The work represents a turning point in the history of cinema. Made in 1926, this adaptation of Goethe's celebrated drama is not a simple screen transposition, but a true re-elaboration of the original work through cinematic language, pushing beyond the formal experimentations of the seminal The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to embrace an unprecedented allegorical grandeur. Murnau masterfully exploits the potential of silent cinema to create a jagged and surreal atmosphere, where shadows lengthen like omens, faces deform to reveal psychological abysses, and reality blends with fantasy in a hypnotic visual ballet. The German director does not merely illustrate the story of Faust but reinvents it, creating a visually powerful and emotionally engaging work that profoundly marked European cinema, whose echo would resonate even in 1930s Hollywood horror productions, especially those from Universal, which borrowed its masterful use of chiaroscuro and monumental set design.

The plot faithfully follows Goethe's drama, yet its transposition reveals additional layers of meaning. The pact between Faust and Mephistopheles, eternal youth, ephemeral beauty, and eternal damnation are all themes explored deeply and evocatively, transforming into archetypes of the eternal struggle between spirit and matter. Through a series of dreamlike and hallucinatory sequences, which are the cinematic counterpart of Goethe's interior monologue and most lyrical descriptions, Murnau immerses us in Faust's inner world, a man tormented by a thirst for knowledge and a desire for power. The figure of Mephistopheles, portrayed by a masterful Emil Jannings (we recall him as the splendid protagonist in The Last Laugh, where his physicality could express the inexpressible), is at once fascinating and unsettling, an ambiguous devil who seduces and corrupts not only with the promise of pleasures but with subtle intellectual insinuation, making him a tempter far more complex than a mere personification of evil. His is a performance that balances the grotesque with a solemn gravitas, an embodiment of Evil that seduces by its very grandeur and intelligence. The tragic yet redemptive ending, through the purifying power of love, leaves a profound impression on the viewer, raising questions about the nature of good and evil, mortality and immortality, and the human soul's capacity to transcend its own corruption.

A mystical parable in which one questions the subtle boundary dividing man from the Supernatural, a force that is not only external and acts upon man, but is also a mirror of the human soul. Faust's fears, desires, and obsessions manifest through the visions and hallucinations that torment him, making the film a descent into the abysses of the psyche, where the fantastic becomes the externalization of the repressed and the desired. Noteworthy in this regard are the technical devices Murnau employs to serve this idea: the characters' faces deform, stretching or flattening, to underscore their emotions and inner torments, an aesthetic borrowed from the pictorial and theatrical avant-garde movements of the time. Landscapes are often filmed with low light, becoming eerie and surreal, a triumph of chiaroscuro that not only creates an atmosphere of mystery and anguish but elevates the landscape to a state of mind, a dramatic element in itself.

Enormous economic resources for what was considered the first true major European production. With a budget of a hefty 2 million marks, it was one of the most expensive films ever made up to that point, an investment by UFA (Universum-Film AG) that aimed to compete with growing Hollywood hegemony, demonstrating the German film industry's capacity to produce works of epic scope and artistic ambition. This substantial sum of money allowed Murnau to create a visually lavish and ambitious film, featuring cutting-edge special effects for the time – such as impressive miniatures, double exposures for spectral appearances, or Mephistopheles' iconic gigantic shadow looming over the city – and grandiose set designs, capable of evoking both cosmic scale and the most intimate human drama.

One of the film's most emblematic scenes is that in which Faust, after signing the pact with Mephistopheles, finds himself in a world of pleasures and sensations. The scene is rich in symbolism, a true danse macabre between luxury and corruption: the dancing women represent the temptations of the flesh, wine symbolizes intoxication and folly, while the music (at the time performed live, often with symphony orchestras) creates an atmosphere of exaltation and decadence. At the same time, the scene is permeated by a profound sense of melancholy and precariousness, underscoring the ephemeral nature of earthly pleasures, a reference to the Vanitas allegories found in Nordic painting. It is in these moments that Murnau demonstrates his mastery in merging the sensual with the spiritual, the grandiose with the tragic. Ultimately, it is a work that powerfully blended lyricism and iconography, borrowing from centuries of art and mythology to forge a wholly new cinematic language, masterfully utilizing the means at its disposal. Faust is not just a silent film masterpiece; it is an authentic school of stylistics, an invaluable treasure for the Cinema of the future, whose influence can be traced in generations of directors, from Orson Welles to Ridley Scott, who have drawn upon its ability to create immersive visual worlds and narratives that transcend mere storytelling to become explorations of the human soul.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...