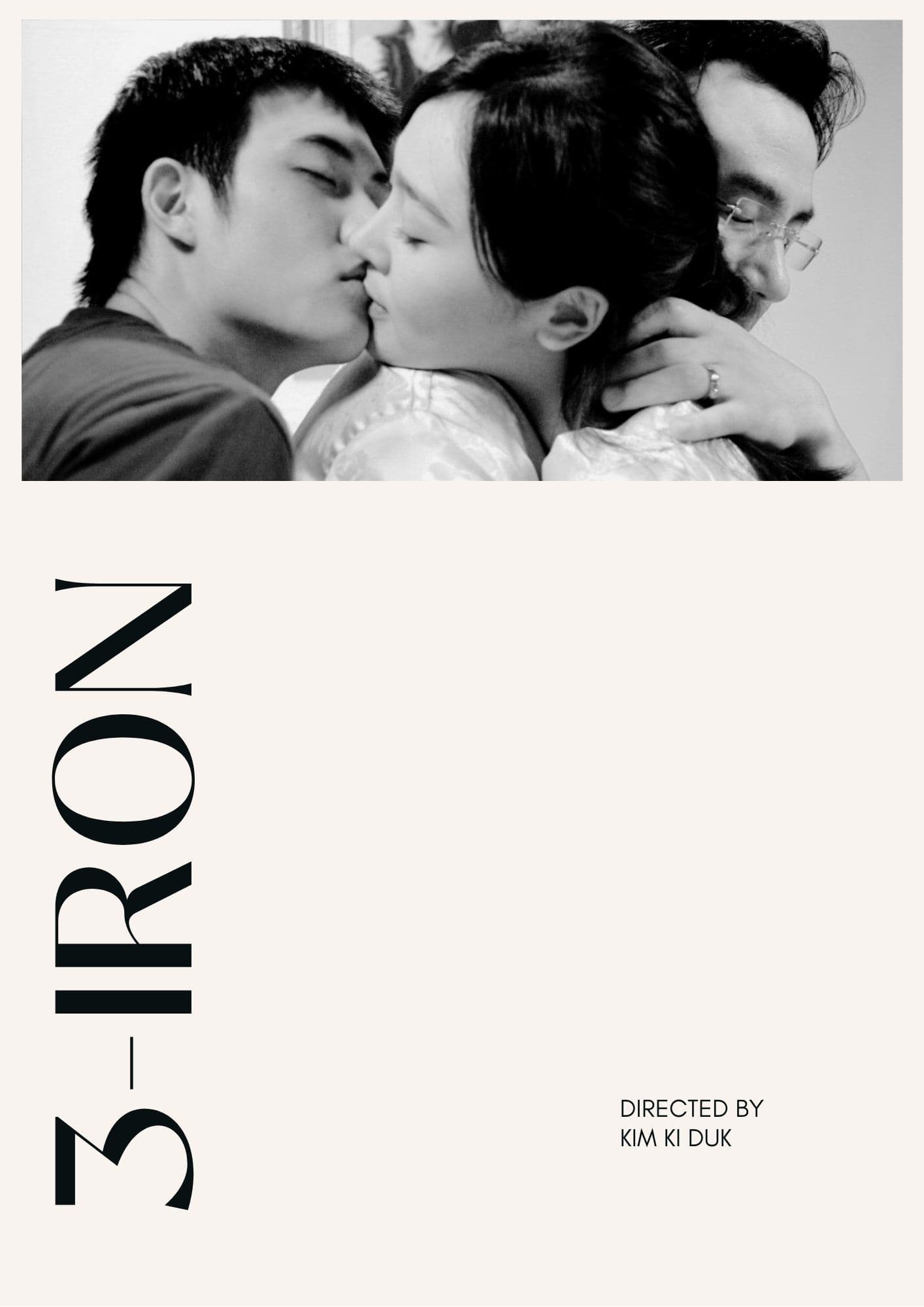

3-Iron

2004

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Kim Ki-Duk is an eclectic artist whose directorial activity is only a small part of his craftsmanship in the field of Art. He is not a filmmaker trained in traditional academies, but an authentic self-made man who shaped his vision through a self-taught path, first as a painter and then as a visual storyteller. This unconventional approach allowed him to develop a thoroughly personal cinematic grammar, detached from conventions and imbued with a powerful evocative force.

A visionary storyteller who began his training in the figurative arts and only recently turned to the Seventh Art. His transition from easel to camera is evident in every frame, where visual composition takes on an almost pictorial centrality, far outweighing the importance of verbal dialogue. He debuted in cinema in 1996 with a biting and original first work like Crocodile, a manifesto of raw vitality and existential marginality, which already foreshadowed his predilection for characters on the fringes of society. Before this film, he authored the wonderful Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003), a Buddhist elegy that, with its meditative progression of seasons and its cyclical narrative of monastic life, had already demonstrated his ability to weave profound and spiritual narratives with a parsimony of words that anticipated the almost total absence of dialogue in 3-Iron.

His works are pure iconographic lyricism, an immaculate flow of ethereal forms and emotions, almost imperceptible in their lingering. Kim Ki-Duk manages to sublimate the most brutal reality into a form of visual poetry that approaches silent cinema, entrusting the task of conveying the most hidden feelings to body language, gazes, ambient sounds, and colors. An aesthetic of the essential, where the unsaid resonates louder than any line of dialogue, inviting the viewer to an empathetic and contemplative participation. Silence is not absence, but a vibrant presence, a connective tissue that binds characters and envelops spaces, allowing the unconscious to emerge and the most intimate feelings to communicate beyond logic and words. It is a bold choice, reminiscent in part of the austerity of a Robert Bresson in his search for purified authenticity, albeit with a deeply Asian aesthetic and spiritual imprint.

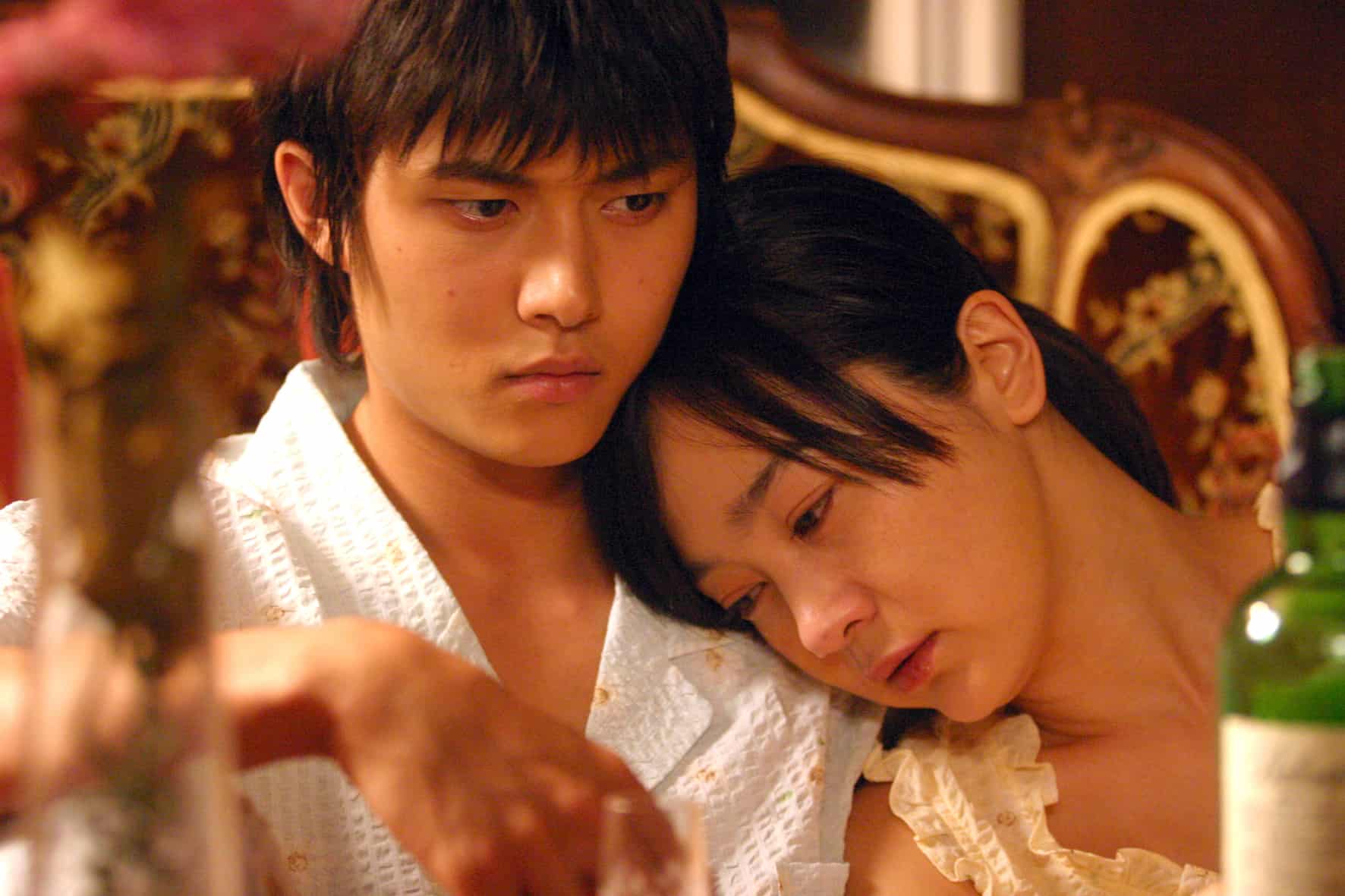

This beautiful 3-Iron - The Empty House is no exception, in which Tae Suk, portrayed with ethereal delicacy by Jae Hee, lives by slipping into temporarily empty houses and making them his own. His intrusions are not acts of vandalism or theft, but rather rituals of occupation and care. Each house becomes a stage for an intimate performance: he repairs broken objects, cleans with almost obsessive meticulousness, plays golf in empty gardens, practicing his imaginary swing against a tree or a statue. He cares for the memories of those who inhabited those houses and guards them almost like an ancient Lares, a household deity, an invisible guardian who restores harmony where absence has left a void. Tae Suk's existence is liminal, a solitary soul who finds meaning in the restoration of what has been abandoned, a spiritual nomad who feeds on the lives of others without ever possessing them. The empty house becomes a temporary refuge for him, a blank canvas onto which he projects his need for belonging and his innate kindness.

In one of his ventures, the young man encounters Sun-hwa (Lee Seung-yeon), a girl who has suffered domestic violence, reduced to a pitiable state, a prisoner in her own home and an abusive marriage. The young man, instead of fleeing or reporting her, takes her with him, drawing her into his game of invisibility and escape, in a pact of silence and complicity that is deeper than any verbal declaration. Inevitably, a diaphanous, unearthly love is born between them, nurtured not by words or grand gestures, but by a profound resonance of their marginalized souls. Their relationship is a ballet of meaningful gestures and intense gazes, a non-verbal language that communicates a sense of mutual recognition and salvation. Tae Suk and Sun-hwa become a refuge for each other, a mirror, an echo of their sufferings and their silent hopes. Their union is a hymn to the human capacity to find connection and affection even in the most desperate conditions, transforming fragility into an almost mystical form of resilience. The boundary between reality and hallucination becomes increasingly blurred, culminating in an ending that challenges sensory perception and suggests a dimension of existence where bodies are no longer bound by physics, but inhabit a plane invisible to the eyes of the ordinary world.

A work that is sinuous poetry of images and sensations, a long, heartfelt tribute to what we have and what we would like to have, a lyrical gaze at the infinite lightness of living. 3-Iron is a meditation on the house not as a physical structure, but as a space of the soul, a keeper of memories and a theater of our most intimate existences. It is an invitation to look beyond the surface, to perceive the "third iron" of the original title ("3-Iron" refers to the golf club, but the Korean title "Bin-jip" means "empty house") which the director himself suggested could symbolize invisibility, the ability to move between dimensions, or the capacity to see and feel what most people ignore. Lightness is not superficiality, but the ability to transcend pain and loneliness through the beauty of the invisible and the strength of a love that needs no words to exist. A film that seeps into the soul, leaving a persistent echo of melancholy and hope, confirming Kim Ki-Duk as one of the undisputed masters of contemporary cinema, capable of elevating the ordinary to the extraordinary with the grace of a painter and the depth of a philosopher.

Main Actors

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...