Breathless

1960

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Godard plunges his electrifying gaze into the metropolitan chaos, into the alienation and anarchy of petty crime, with a sardonic and irreverent eye. This is not a mere chronicle, but an incisive examination of post-war existentialism, an era in which certainties crumbled and the individual found themselves navigating a world devoid of cardinal points, driven by an almost nihilistic impulse. This is the cinema of an auteur who is not afraid to break conventions, transforming the gritty street realism into a stage for a philosophical drama disguised as a polar.

The result is a work of dazzling brilliance, where irony, nonsense, and a love for the surreal create amusing dialogues, in which camera mastery and semantic jumps reveal its primal beauty. That beauty is not polished or glossy like in classic Hollywood cinema, but raw, vibrant, almost unrefined, like a freshly extracted diamond. It is the beauty of rupture, of stylistic disobedience that would soon become the distinctive hallmark of the Nouvelle Vague. The celebrated jump cuts, at the time seen as technical errors, are not here casual oversights, but deliberately unconventional choices that break spatiotemporal continuity to accelerate the narrative rhythm and, above all, to shake the viewer out of their passivity, making them aware of the filmic construction. It is a gut punch to the cinematic rhetoric of the time, a declaration that cinema can and must be something more than a simple linear narrative. Godard, with this electrifying debut, draws not only from the tradition of American film noir – of which he was a passionate critic – but reinterprets it through an exquisitely European lens, infused with literary influences from Albert Camus to Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

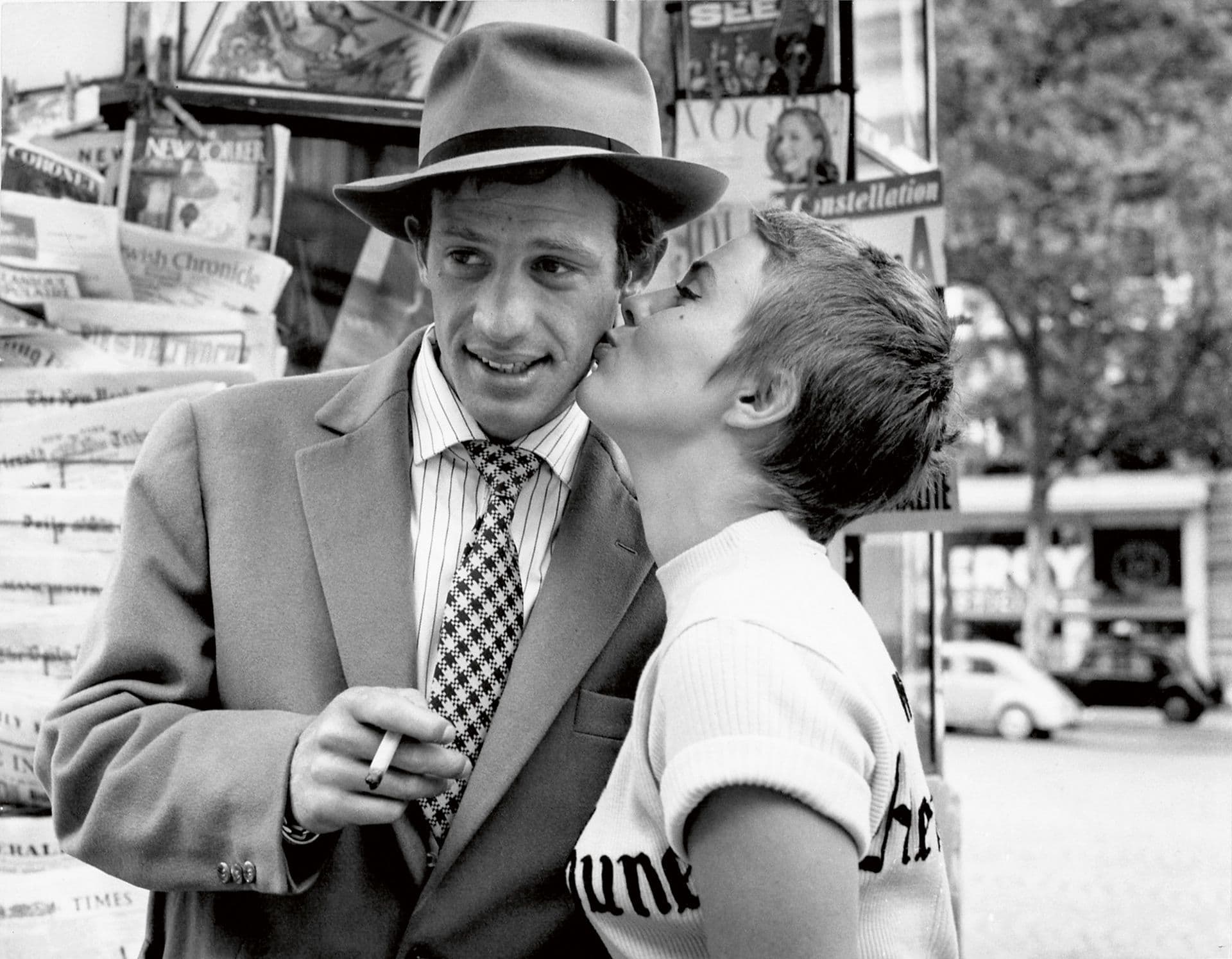

Jean Paul Belmondo is a petty car thief who kills a policeman after being stopped for a traffic violation. Michel Poiccard, his character, is not the romantic hero or the monolithic villain: he is a disillusioned anti-hero, a modern and amoral flâneur, whose identity is partly a performance, a swaggering and unsuccessful imitation of Humphrey Bogart, his cinematic idol. It is no coincidence that we see him light a cigarette by rubbing his thumb over his lips, a gesture stolen from the film noir icon. This explicit quotation is not a simple homage, but a meta-cinematographic comment on the very nature of the character and of cinema: we are all actors in a play, and reality is often an imitation of art.

An escape begins in an anarchic and teeming Paris, where the protagonist will rediscover a total and alienating feeling towards an old flame, played by the beautiful Jean Seberg. Patricia Franchini, the American student, embodies modernity and a female independence that challenges the conventions of the era. Her measured English, her pixie haircut, her moral ambiguity make her as captivating as she is enigmatic. Their relationship is not the passionate and all-consuming one of melodramatic cinema, but a tango of seduction and repulsion, of dependence and a desire for freedom, a verbal and physical duel in which every word, every gesture, is charged with a subtle power play.

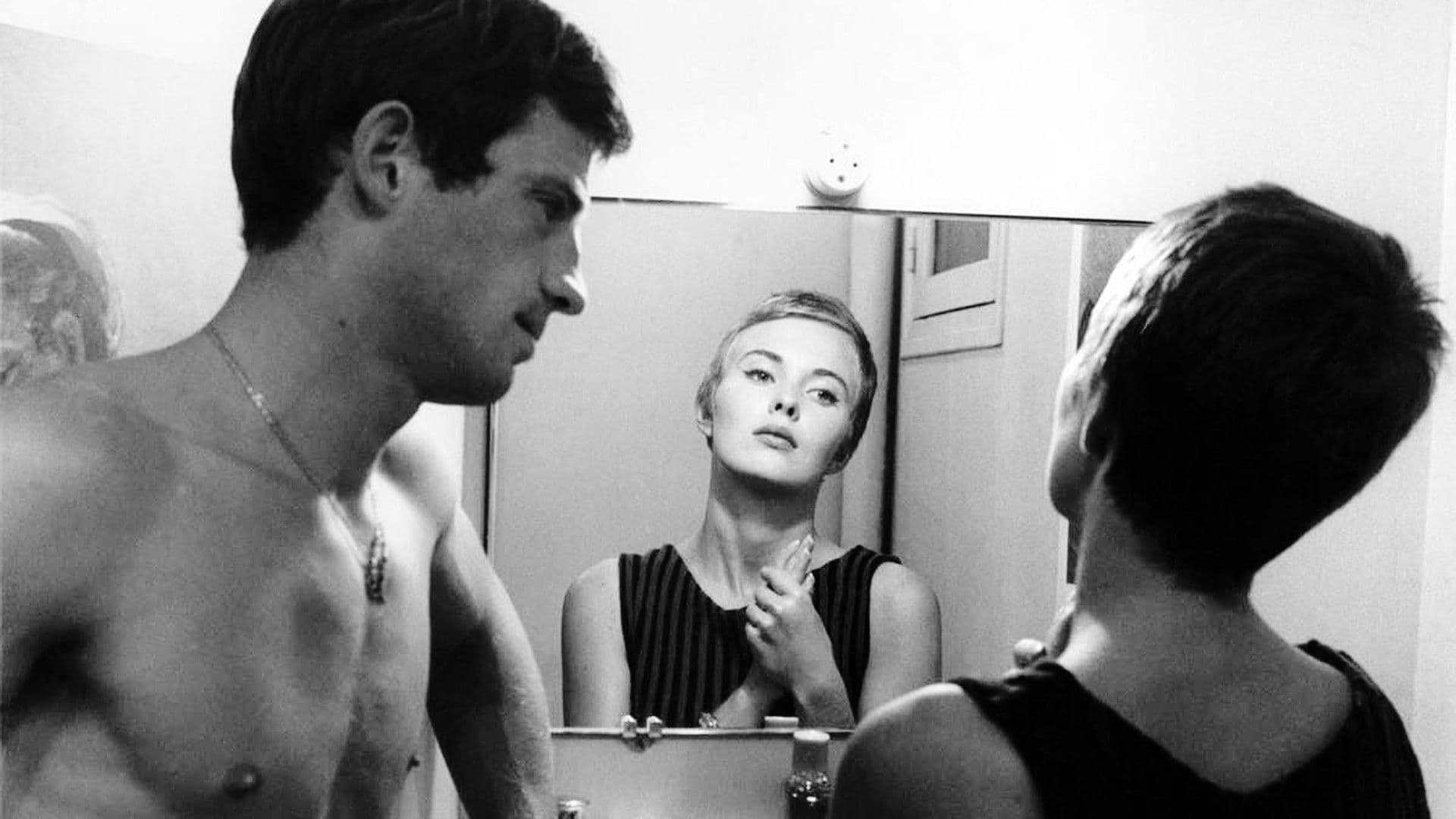

An ironic love will emerge from this, amidst funny quarrels and eternal promises, amidst grotesque chases and elaborate love scenes. Godard exploits the spontaneity of his actors and the limited resources of the production – the film was shot with a reduced crew, often without synchronized sound and with improvised dialogues on set – to create an atmosphere of raw authenticity. The "elaborate love scenes," rather than passionate, appear as studied choreographies, almost a narrative obligation to which the characters conform with a certain inertia, highlighting their incapacity for authentic connection in a world of appearances and fleeting pleasures. The famous long and dialogic hotel room sequence is a microcosm of their relationship: a seesaw between intimacy and distance, between a genuine desire and a cold rationality that will ultimately prevail. This scene, in particular, has become an icon of Godardian cinema, demonstrating how the absence of action can be more powerful than a thousand chases.

Following this strange couple, the film reaches its tragic epilogue. An epilogue that is not a dramatic twist, but the logical conclusion of a destiny already written, an ineluctability that permeates the entire narrative. Michel's end is not so much a punishment for his crimes as the inevitable dissipation of a transient existence, a final gasp before silence.

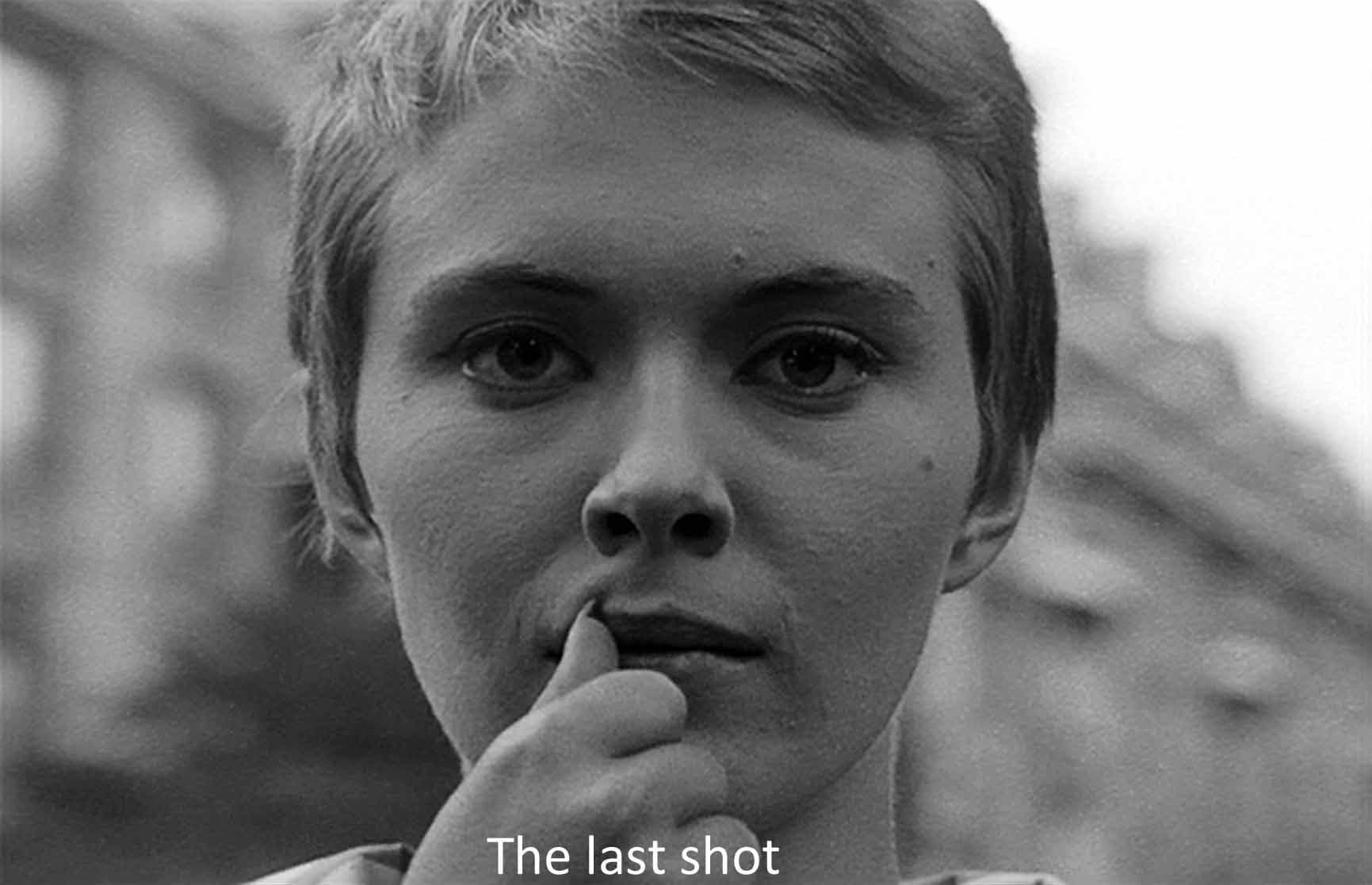

The final scene is memorable in its stylistic precision: Belmondo, fatally wounded, vainly pursues a car until he collapses to the ground in the middle of an intersection. Jean Seberg arrives and watches him die almost with detachment, then with tenderness, wondering what his last words were, touches her lips with a circular thumb movement, looking intensely into the lens. Her gaze directed at the viewer is the final breaking of the fourth wall, a meta-cinematographic gesture that demolishes the cinematic illusion and makes us complicit, or perhaps impotent witnesses, to a drama that is simultaneously fiction and a reflection of reality. That touch on the lip, an ambiguous and iconic gesture, is an enigma that has generated endless interpretations: is it the memory of the kiss, a nervous tic, a reproduction of the "dégueulasse" (disgusting) gesture that Michel had directed at her? Whatever its origin, it is the last flicker of a complex and contradictory emotion, a farewell to an ephemeral love and a lost innocence.

A paradigmatic film for understanding what the Nouvelle Vague was, who gave it artistic lifeblood, and to what extent. "À bout de souffle," whose original title evokes a sense of breathlessness and despair, is not just a milestone of French cinema; it is a manifesto, a cultural earthquake that redefined cinematic language for generations to come. Without this film, the auteurial approach, narrative freedom, and the subversive use of form would have been unthinkable for many of the directors who followed him, from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino, not to mention an entire wave of independent cinema that found its spiritual godfather in Godard. A work that, more than sixty years after its release, retains its disruptive power and its capacity to make us reflect on cinema, on life, and on the elusive nature of identity.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...