For Love and Gold

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Monicelli writes and directs a comic work, using the double-edged sword of crude parody and developing an almost surreal character, poised between Cervantes and Rabelais. But his mastery goes far beyond mere jest: here the operation is a wise and bitter deconstruction of the epic-chivalric genre, a demolition of the founding myths that post-war Italy, still clinging to grandiloquent narratives, struggled to overcome. Brancaleone's Army is not just a band of misfits, but the quintessence of an eternal Italy, facing the abyss of misery yet capable of finding in its own buffoonery an inextirpable form of resilience. Brancaleone himself is not Cervantes' noble yet mad Don Quixote, but rather an amalgam of his skewed idealism and the clumsy corporeality, greed, and grotesque vitality of a Rabelaisian Gargantua, set in a Middle Ages not of chivalric romance but of sordid chronicle, of mud, hunger, and superstition.

A group of vagabond idlers, a motley crew of human miseries and walking cardinal sins, comes into possession of a parchment that attests to the ownership of the Apulian citadel of Aurocastro. It is not gold that drives them, but an almost biblical hope, albeit corrupted and illusory, of a "Promised Land" which will reveal itself, like every promise in Monicelli's world, to be yet another mocking mirage. The ramshackle platoon elects the knight Brancaleone as leader of that enterprise and sets off towards their supposed fortune, on a journey that is the archetype of the picaresque voyage: an episodic odyssey through an inhospitable land populated by bizarre figures, where survival is the true epic and failure the only certainty.

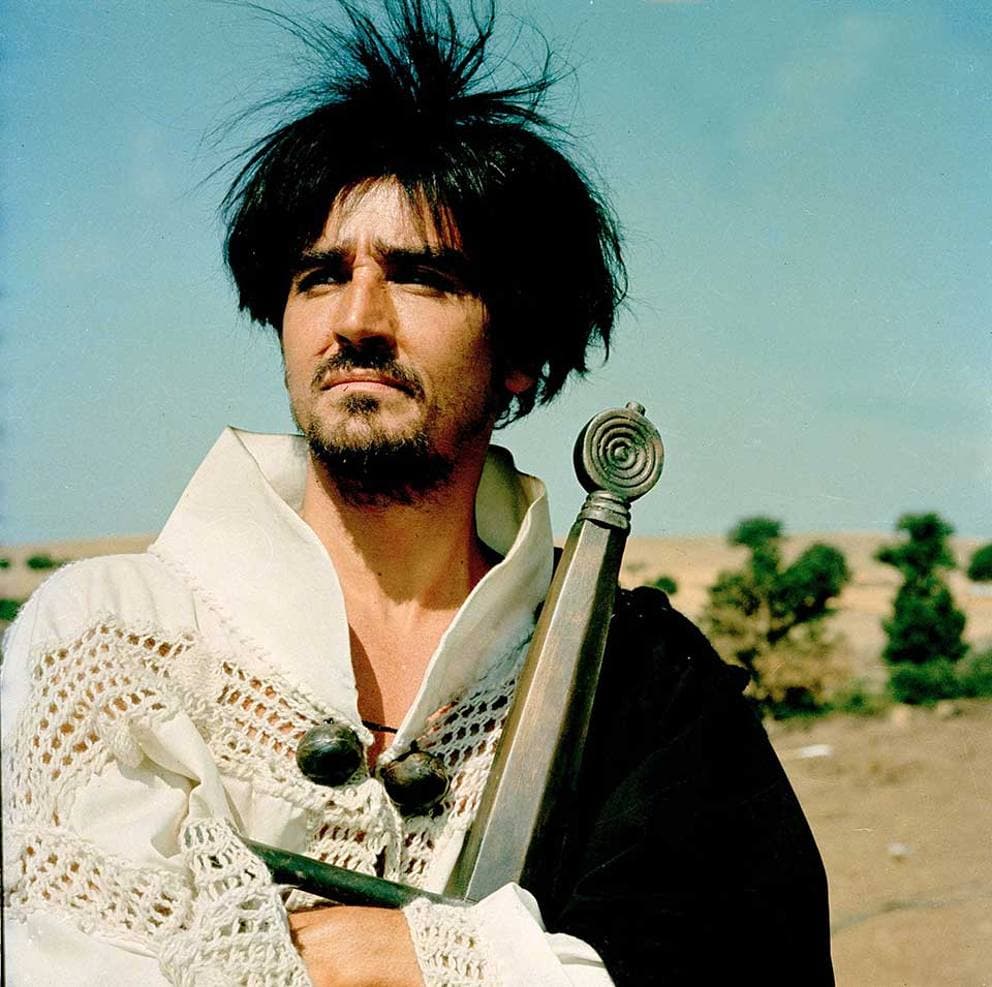

Needless to say, the journey will be strewn with unforeseen events and adventures of all kinds that will highlight the chivalrous buffoonery of the valiant Brancaleone. His "prowess" is a monument to vainglory, a purely theatrical display of courage, destined to clash every time with the rawest and most comical of realities. He is the anti-hero par excellence, the Monicellian figure of the unfortunate who deludes himself with grandeur, destined to stumble every time, but with a ramshackle dignity and an irresistible rhetoric. An epic failure, glorious in its total ineptitude, which becomes the film's true stylistic signature.

Two scenes we wish to recall for their inimitable comic force and their sociolinguistic acuity. The first is Brancaleone's bombastic speech to his troop before setting off on the enterprise, where he promises his valiant men treasures and fair maidens: "Silence! I am your leader! And therefore you owe me obedience and dedication. Our path shall be strewn with sweat, tears, and blood. Are you ready for so much? Respond in one voice. Are you ready to die fighting? We shall march for days, weeks, and months, but in the end we shall have castles, riches, and fair maidens with large bosoms." This is not a simple monologue: it is a verbal symphony, an immersion into "Brancaleonesque," the language invented by Monicelli and Age & Scarpelli, a brilliant blend of medieval vulgar tongue, macaronic Latin, distorted archaic expressions, and irresistibly popular comedic lines. Gassman shapes it with his deep and resonant voice, transforming every phrase into a phonetic work of art, a precarious balance between the sublime and the ridiculous, which elevates braggadocio to an art form.

The second scene to remember is the duel with the roguish Teofilatto dei Leonzi (played by a Volontè evidently at ease even in comedic roles), where in the fury of the contest (and amidst the many truces imposed by a dispute more bureaucratic than warlike) the two clear-cut and lay waste to the landscape. The presence of Gian Maria Volontè, an iconic actor of committed and dramatic cinema, in such a caricatural role is a touch of Monicellian genius, underscoring his versatility and his ability to immerse himself in extreme characters. The duel itself is an allegory of obtuse and vain destructiveness, a dance of incompetence that leaves behind only devastation, a landscape no longer bucolic but scarred by the swords of the two "valiant ones" in an image of surreal, almost cartoonish, violence. Every interruption, every negotiation, every truce to drink or rest makes the absurdity of the conflict even more palpable, in a biting portrait of the Italian art of getting by and, paradoxically, even procrastinating violence.

But other memorable passages cannot be overlooked: the encounter with the monk Zenone (Folco Lulli), a prophet of doom and bringer of plagues, an emblem of a popular religiosity imbued with fatalism and superstition; or the figure of the nun Teodora (Maria Grazia Buccella), an object of desire and salvation, who adds an element of clumsy and sacrilegious eroticism. These characters, like the entire platoon of wretched individuals who follow Brancaleone – Pigna, Mangoldo, Taccone, the dwarf Gherardo – are archetypes of commedia all'italiana, figures who, even in their grotesque exaggeration, reflect a bitter and truthful cross-section of humanity perpetually poised between hunger and hope, ignorance and an irrepressible drive towards a never-achieved redemption.

A work of extraordinary comic power, enhanced by the mimetic and colossal performance of Vittorio Gassman, who bestows upon the character an aura of mystical braggadocio but also a profound, almost poignant, humanity. Brancaleone is a compendium of tics and poses, but he is also a man desperately seeking meaning, dignity, even if only in the most brazen of lies. His physical clumsiness, his vocal pomposity, his gaze perpetually oscillating between dreaminess and disillusionment, are the tools with which Gassman sculpts an iconic character, rightfully embedded in the Italian collective imagination.

"L'Armata Brancaleone" is not just an amusing comedy; it is an anthropological essay on the nature of the average Italian, an allegory of their tendency to idealize defeat, to transform failure into legend. The film, almost sixty years after its release, retains its satirical force and surprising modernity intact, testifying to Monicelli's ability to read the deep soul of a country through the acidic and disenchanted lens of laughter. It is a timeless masterpiece, a bitter and brilliant elegy to glorious, unstoppable human buffoonery.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...