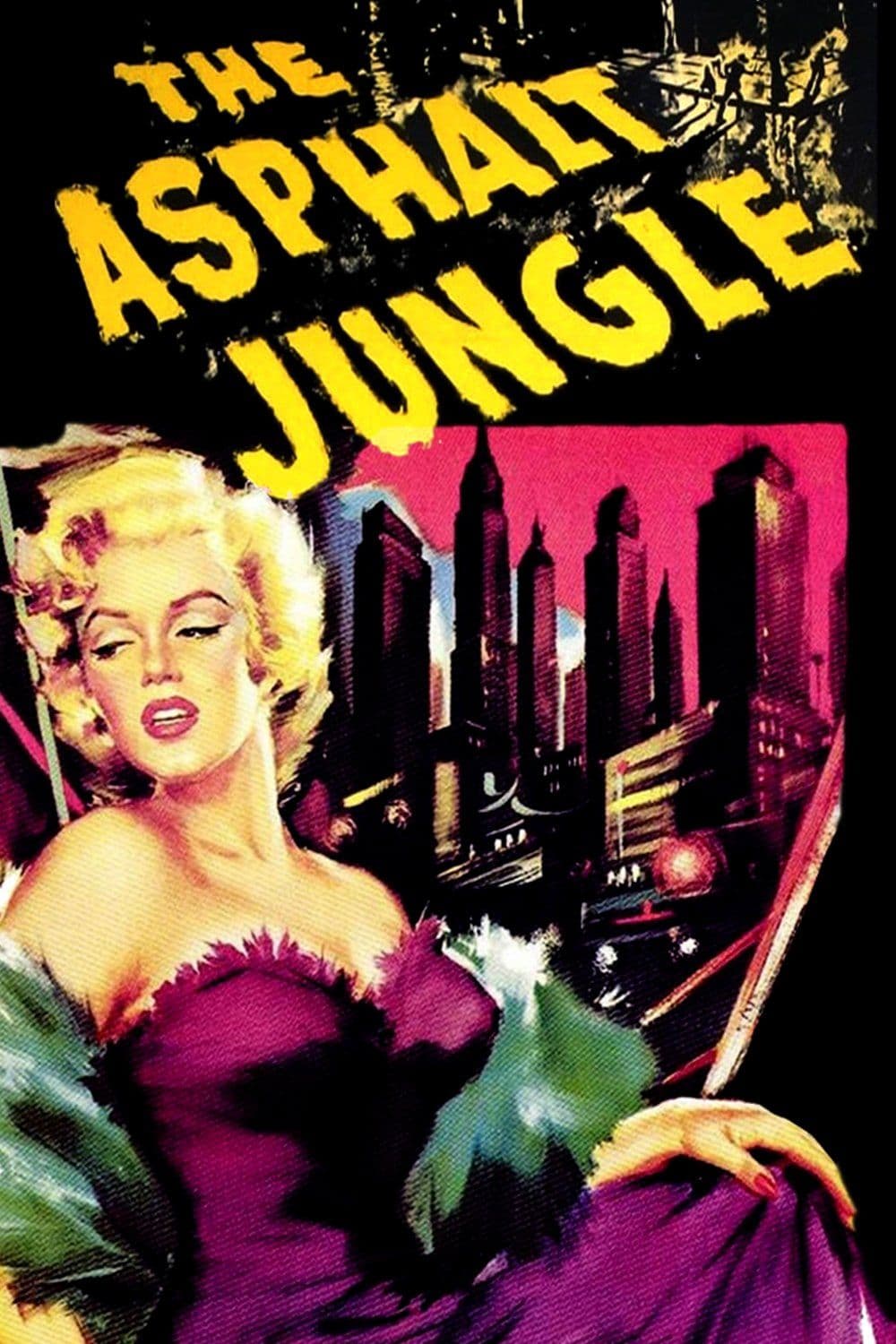

The Asphalt Jungle

1950

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Huston delivers one of the most beautiful noir-tinged gangster movies ever, doing so with a lightness and at the same time a depth of insight that have made it a cornerstone of the genre. It is not merely a crime chronicle, but rather an autopsy of human despair, narrated with an almost clinical lucidity that transcends all rhetoric or moralistic judgment.

Undoubtedly, the best thing about the film is the profound yet schematic portrayal of every character involved in the narrative. This dichotomy – depth and schematism – is Huston's true genius. We are not presented with "round" characters in the most traditional literary sense, with complete narrative arcs and complex psychological backstories, but rather with crystalline human essences, almost living archetypes whose motivations are immediate, palpable in their raw honesty and desperation.

The human element is Michelangelically rendered in its intrinsic specificity: vices, emotions, thoughts, tensions, words, gestures. Like figures sculpted from a block of marble that reveal the naked soul, Huston strips his protagonists bare, bringing their most vulnerable essence to light. They are not simply "criminals"; they are men blinded by unattainable dreams – the farmer yearning for his land, the intellectual pursuing his golden retreat – trapped in a spiral of wrong choices and fatality. The characters are not mere cold symbolic silhouettes in a stylized world; Huston breaks the intellectual barrier of expressionism, allowing them to shine in all their glorious humanity without infusing either rhetoric or pathos. Whereas German expressionism often distorted reality to reflect a subjective and anguished state of mind, Huston opts for a raw realism that, while maintaining the claustrophobic atmosphere of noir, allows faces and gestures to express tragedy without the need for stylistic amplification. Harold Rosson’s camera, with its black-and-white cinematography sculpting light and shadow, is complicit in this operation: it does not falsify reality, but rather exalts it in its dramatic austerity, making the concrete jungle not merely a backdrop, but a silent predator awaiting its inhabitants.

The story takes shape around the plan for a jewelery heist. It is the classic "heist movie" ante litteram, a model that would influence countless subsequent works, from Jules Dassin's Rififi (even though this film preceded it) to Ocean's Eleven, all the way to the complex plots of Quentin Tarantino. The narrative focuses not so much on the "what" but on the "how" and the human "why" of the crime. The mastermind behind the heist is a lawyer on the verge of ruin, Alonzo Emmerich, a man from "respectable" society whose moral frailties prove more dangerous than those of his criminal accomplices. The perpetrators are a heterogeneous gang of diverse humanity, a sample of urban underworld archetypes: the hardened gambler, the intellectual safecracker, the soft-hearted "gorilla". They will carry out the heist but leave faint traces that the police will pounce upon, not so much due to egregious errors as to the infallible law of chance and human fragility. A trivial cough, an error in judgment, the unforeseen breaking through the veil of criminal perfection and revealing the precariousness of every human plan.

It will be the beginning of a slow game of attrition in which every member of the gang inexorably falls into the net. It is the descent into the hell of paranoia and mutual distrust, where ambition clashes with brutal reality and solidarity is merely a facade that crumbles at the slightest breath of wind. The film explores the theme of ineluctable destiny, typical of the darkest noir: once the path of crime is taken, there is no return, only a progressive erosion of the individual. Escape, when attempted, is an illusory mirage, resolving itself in a bitter and poetic irony, like Dix Handley's final journey. Even the brief but iconic appearance of a very young Marilyn Monroe, in the role of Angela Phinlay, Emmerich's mistress, adds a touch of vulnerability and corrupted innocence to this fresco of moral misery, anchoring the film not only to its genre but also to a precise historical and cultural moment in Hollywood.

A reference for many filmmakers who have viscerally loved this film, from Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese, who assimilated its lesson on character construction and the inevitability of the criminal narrative. Huston gave free rein to his great genius, creating a bastion upon which to erect the fortress of the Seventh Art, a model for how a genre story can elevate itself to social commentary and psychological study, a work that, while moving within the stylistic elements of noir, transcends them to offer a universal and ruthless vision of the human condition. It is difficult not to consider this film a timeless masterpiece, a work of almost documentary realism, yet imbued with a poetic melancholy that continues to resonate powerfully with every viewing.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...