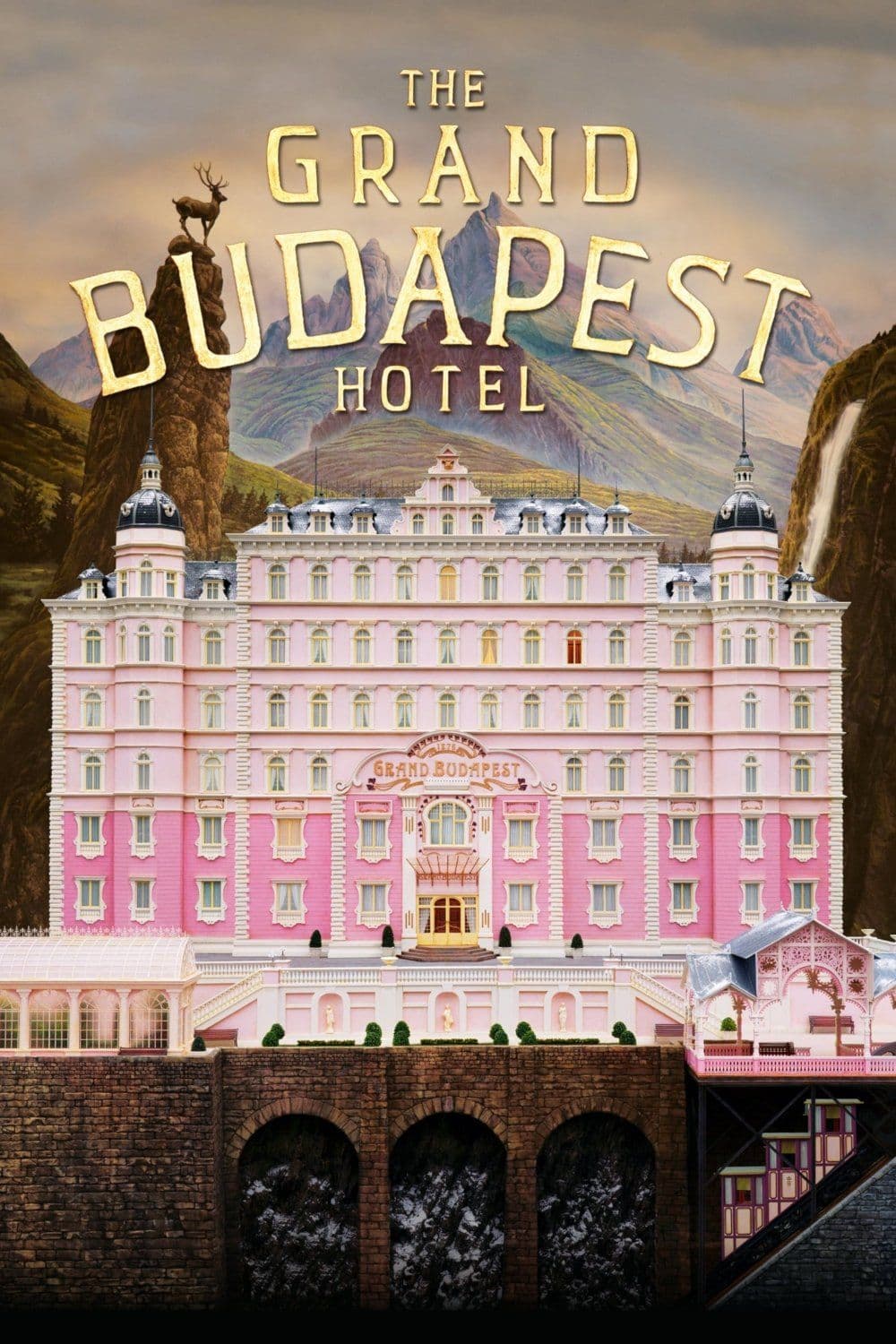

The Grand Budapest Hotel

2014

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Gianni Rodari, in a particularly insightful passage of his essay “Grammatica della Fantasia,” describes the genesis of a fairy tale in its primary creative impulse thus: “The child’s imagination, stimulated to invent words, will apply its tools to all aspects of experience that challenge its creative intervention.

Fairy tales serve mathematics just as mathematics serves fairy tales.

They serve poetry, music, utopia, political commitment: in short, they serve the whole human being, and not just the dreamer.”

Wes Anderson, a great artisan of the fairy tale, seems to literally embrace this tenet of Rodari's, constructing his wonderful iconographic castle of The Grand Budapest Hotel with every tool at his disposal. His is not mere narration, but a true architecture of the imaginary, a laboratory where fantasy manifests itself through the meticulousness of detail, chromatic symphonies, and geometric precision that distinguish it. Every frame is a living diorama, an animated miniature that pulsates with life and an unmistakable aesthetic.

His art in shaping this surreal yet so tremendously apt story for certain fierce episodes of the past seems conscious of the universal message it carries. The film, in fact, while enveloping the viewer in a whirlwind of pastel elegance and refined humor, does not shy away from the task of evoking the looming shadow of European history, that glittering Mitteleuropa destined to be swallowed by the barbarity of totalitarianisms. A distant, yet vibrant, echo of the melancholy of the lost world magnificently described by Stefan Zweig, an author often cited by Anderson himself as a source of inspiration for the atmosphere and the figure of his protagonist.

In 1932, The Grand Budapest Hotel is the flagship of hospitality in the Republic of Zubrowka, a fictional country that serves as a dystopian and stylized mirror of bygone Austria-Hungary. In the grand Hall, celebrities, dignitaries, and Central European nobility succeed one another, a kaleidoscope of characters inhabiting an era nearing its end. Gustave H. is the concierge who serves as a Deus Ex Machina: he issues orders, manages relationships with staff, and public relations with the distinguished guests. He is a gentleman of refined and somewhat grotesque tastes (he enjoys relations with elderly women), he adores poetry and good taste, a guardian of etiquette and an almost anachronistic elegance in a world about to implode. His figure is that of a last bastion of civilization and decorum on the verge of being swept away.

One of his elderly lovers, the very wealthy Madame D., dies in mysterious circumstances and bequeaths to him a precious painting by Johannes Van Hoytl the Younger: "Boy with Apple." Gustave goes to retrieve the painting with Zero Moustafa, the new lobby boy, an orphaned refugee whom he takes under his wing. Their relationship, initially that of master-apprentice, transforms into the emotional heart of the film: a father-son bond that defies conventions and adversities.

Around this painting, which serves as a classic Hitchcockian macguffin, a surreal chess match will soon unfold between relatives disappointed by the will of the departed noblewoman and Gustave. Madame D.'s family, particularly her son Dmitri with his hitman J.G. Jopling (a Willem Dafoe of almost cartoonish ruthlessness), violently and perfidiously opposes the deceased's will. Meanwhile, Gustave is arrested, believed to be implicated in the death of the woman who, in reality, had left not only the painting to Gustave but her entire estate.

A whirlwind of dazzling adventures follows in quick succession, involving: a military invasion by an occupying force strongly reminiscent of the Nazis, with their grim uniforms and brutal intentions that violently clash with the film's aesthetic lightness; a ruthless assassin in the pay of one of the noblewoman's terrible sons; a girl with a birthmark shaped like Mexico on her cheek, the tender and brave Agatha, who will become Zero's love interest; pastries of such supernatural goodness that they can even soften ruthless assassins in prison, the famous Mendl’s, a symbol of an art that persists and fascinates even in chaos; and the list could go on for a long time, including an unforgettable prison escape with a gang of crazy inmates and an epic descent down a ski slope.

Anderson skillfully balances the different formats and aspect ratios (1.37:1 for scenes set in 1932, 2.35:1 for the 1960s, and 1.85:1 for the contemporary narrative frame), not merely as a stylistic exercise, but as an expression of memory that deforms and stratifies, adding layers to the tale of a time gone by. The obsessive use of symmetry, frontal shots, and precise, almost choreographic camera movements, lends the film a unique atmosphere, halfway between a puppet theater and the illustration of a pop-up book, an aesthetic that celebrates form as much as content. The extraordinary ensemble nature of the cast, where every actor, from protagonist Ralph Fiennes to the smallest cameo, merges with the director's vision, contributes to creating a cohesive and irresistible universe.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is a triumph of creativity, fantasy, of wonder whispered in the form of a fable. It is a song of love and regret for a lost era, filtered through the distorted yet profoundly true lens of narration. Wes Anderson becomes an irresistible storyteller in the twilight who seduces us with his iconographic allure, with his sinuous symmetries, with his obliquely astonishing creatures. A cascade of fables overwhelms the viewer, who remains bewildered and smiling, following the fantastic flow, because, to quote Gianni Rodari, every person needs fables to live, not just dreamers, especially when these fables, in their apparent lightness, can speak to us of the transience of things and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of history.

Main Actors

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...