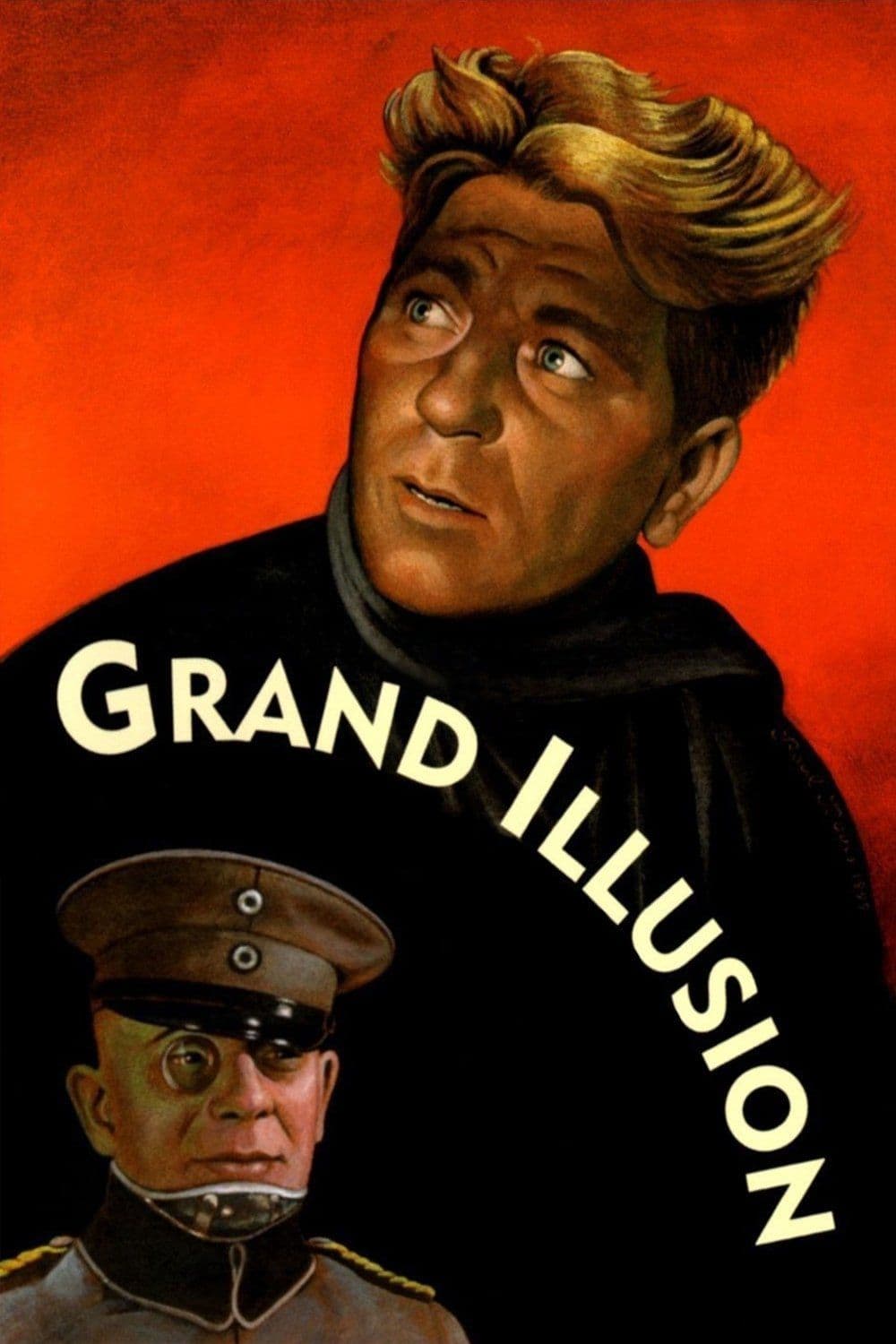

Grand Illusion

1937

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

An work that makes the anti-war message the cornerstone of its artistic vision. Jean Renoir directs with a sensibility that transcends any attempt to categorize his film, crafting a work that still impresses today with its modernity, with its semiotic power. At the heart of the French poetic realism movement, Renoir distinguishes himself with a radical humanism and an almost prophetic ability to read the times to come. Filmed in 1937, a few years before the outbreak of the Second World War, in a Europe already traversed by the sinister winds of nationalism and authoritarianism, the film is a deafening cry against the folly of war and a moving hymn to the brotherhood of man. Renoir, with a clear-sighted and disenchanted gaze, analyzes the social and psychological dynamics of conflict, highlighting the absurdity of national divisions and ideological barriers which ultimately prove futile and precarious in the face of the common human condition.

La Grande Illusion is a film that has indelibly marked the history of cinema, not only for its thematic importance but also for its impeccable formal beauty. Christian Matras' cinematography, with its masterful chiaroscuro and rarefied atmospheres, does not merely illuminate the scene but actively contributes to creating a palpable atmosphere of melancholy and disillusionment, almost a premonition of the twilight of an entire civilization. Each shot is imbued with an austere realism that blends with a subtle lyricism, lending the film an almost pictorial dimension. The actors' performances, among which stand out Jean Gabin's subtle nobility, Pierre Fresnay's melancholic elegance, and Erich von Stroheim's tragic gravitas, are intense and memorable, true archetypes of a complex and stratified humanity.

During the First World War, two French officers, Captain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) and Lieutenant Maréchal (Jean Gabin), are shot down and taken prisoner by the Germans. The encounter between the refined aristocrat Boeldieu and the pragmatic, more proletarian Maréchal is in itself a microcosm of the social tensions of the era, a fracture that imprisonment and shared suffering attempt to mend. They are transferred to different prisoner-of-war camps, a visual metaphor for existential claustrophobia and loss of freedom, where they meet other prisoners of various nationalities and social standings. Among them is Lieutenant Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio), a wealthy Jew, a figure Renoir introduces with delicacy but profound meaning, even more so in light of the events that would soon blight Europe, with whom they forge a deep friendship. The narrative proceeds with an almost documentary-like fluidity, yet every interaction, every glance, reveals layers of meaning. In the prison camp commanded by Captain von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), a German aristocrat wounded in the war, a relationship of mutual respect and esteem develops between the two officers, despite being on opposing sides. This bond between Boeldieu and von Rauffenstein is the beating heart of the film, a swan song for a cosmopolitan and idealistic European aristocracy, whose conventions of honor and chivalry are about to be swept away by the brutality of modern warfare. Their mutual respect, transcending the trenches, suggests a class solidarity that crosses national borders, a revolutionary viewpoint for the time. De Boeldieu and Maréchal organize an escape plan, but de Boeldieu, in an act of supreme nobility and sacrifice, sacrifices himself to allow Maréchal and Rosenthal to escape. His death is not merely a heroic act, but the painful extinction of an era, the end of a certain type of elite destined to disappear, leaving the field open to more earthly and concrete figures like Maréchal. The two fugitives, after a perilous journey across Germany, find refuge with a German widow (Dita Parlo), with whom Maréchal forms a brief but intense relationship. This idyllic and tragically ephemeral interlude, in which human tenderness blossoms despite the hatred of war, is a powerful counterpoint to the harsh reality of the camps, a glimmer of hope and normality. Finally, they manage to reach the Swiss border and make it to safety, a journey towards freedom which is also a journey towards new awareness.

Memorable is the scene where the prisoners are forced to humiliate themselves by dressing as women for the mockery of the German officers. This sequence, ostensibly a moment of farce, is in reality a masterpiece of psychological and political subtlety. During the performance, however, they begin to sing the Marseillaise. The scene is characterized by intense irony, but also by profound dignity. The German officers, who believe they are humiliating the prisoners, end up being defeated by their own weapon: the patriotic song, not out of blind nationalism, but for a rediscovered identity and resistance. The prisoners, singing the Marseillaise at the top of their voices, transform the act of humiliation into an act of collective resistance and defiance, an affirmation of their irrepressible humanity. The song, initially off-key and uncertain, grows progressively stronger and more choral, a symbol of rediscovered unity and patriotism, a wave of sound rising above the camp walls. Renoir, with a humanist and anti-militarist gaze that transcends all partisanship, shows us how war is a "great illusion," a deception that destroys lives, obliterates social classes, and creates only suffering. A work of stunning iconic beauty and great emotional impact that has influenced numerous cinematic works such as David Lean's The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), where similar themes are explored, such as the relationship between officers of different nationalities, the sense of honor and duty, and the constructive and destructive madness of war. But the influence of La Grande Illusion extends far beyond, touching the collective imagination of countless films about imprisonment and brotherhood in adverse contexts, from Stalag 17 to the psychological depth of Paths of Glory, despite their diversity of tones. The film was met with great enthusiasm by international critics and audiences, winning the award for Best Film at the Venice Film Festival in 1937, a bold recognition in an Italy already under the grip of the fascist regime, which indeed banned it shortly thereafter, as did Goebbels' Nazi Germany, precisely because of its universal message of peace and humanity that undermined the foundations of bellicose ideology. An authentic masterpiece that continues to dazzle us today and reminds us, with disarming force, of the enduring importance of overcoming ideological and cultural barriers to build a world based on respect and mutual understanding.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...