Harakiri

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

During its golden age, samurai cinema was a two-faced Janus, with two faces looking at the history and myth of feudal Japan from complementary but distinct perspectives. On one side was the face of Akira Kurosawa; on the other, the perhaps more angular and politically radical face of Masaki Kobayashi. While Kurosawa, despite all his humanism and social criticism, retained a vein of romanticism and a belief in the possibility of heroic action, Kobayashi, with his absolute masterpiece Harakiri (1962), took the same iconography of the Japanese warrior and used it to perform a ruthless vivisection of power, a relentless indictment of the hypocrisy of an entire value system.

This is not a samurai film; it is a film against the code of Bushidō, a Greek tragedy dressed up as jidaigeki whose sharp blade is not the katana but logic. The parallel with Kurosawa is therefore inevitable, but by antithesis.

Both are the greatest exponents of a new wave of Japanese cinema in the 1960s, poised between historical revisionism and iconographic celebration, but with different intentions. Kurosawa, in works such as The Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, explores the morality of the individual within the code, finding nobility even in defeat and marginalization. Kobayashi, on the other hand, demonstrates how the code itself, when it becomes a dogma emptied of all compassion, is transformed into an instrument of institutional sadism. His cinema is one of almost absolute political lucidity and pessimism, where honor is only a mask for the cruelty of power.

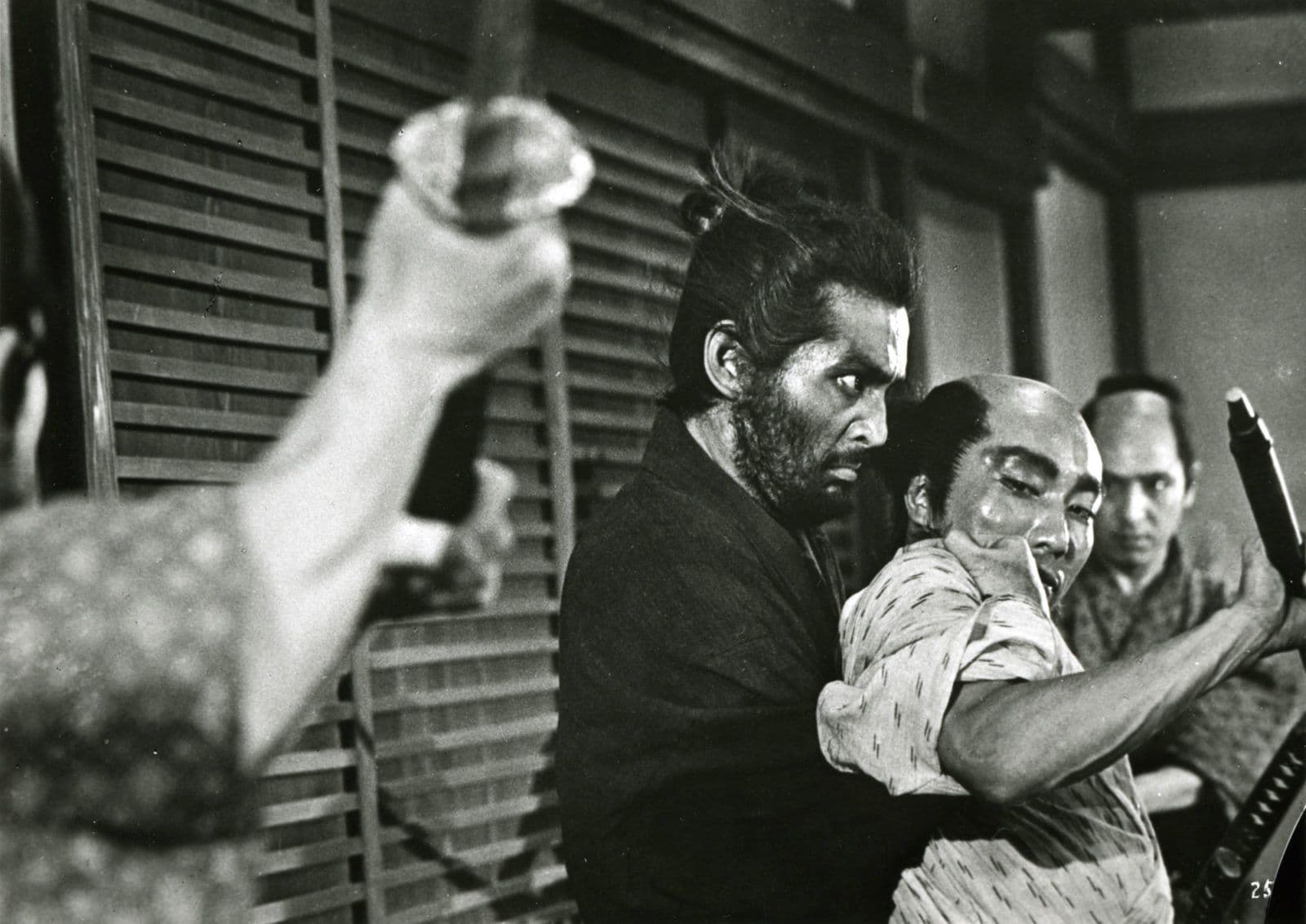

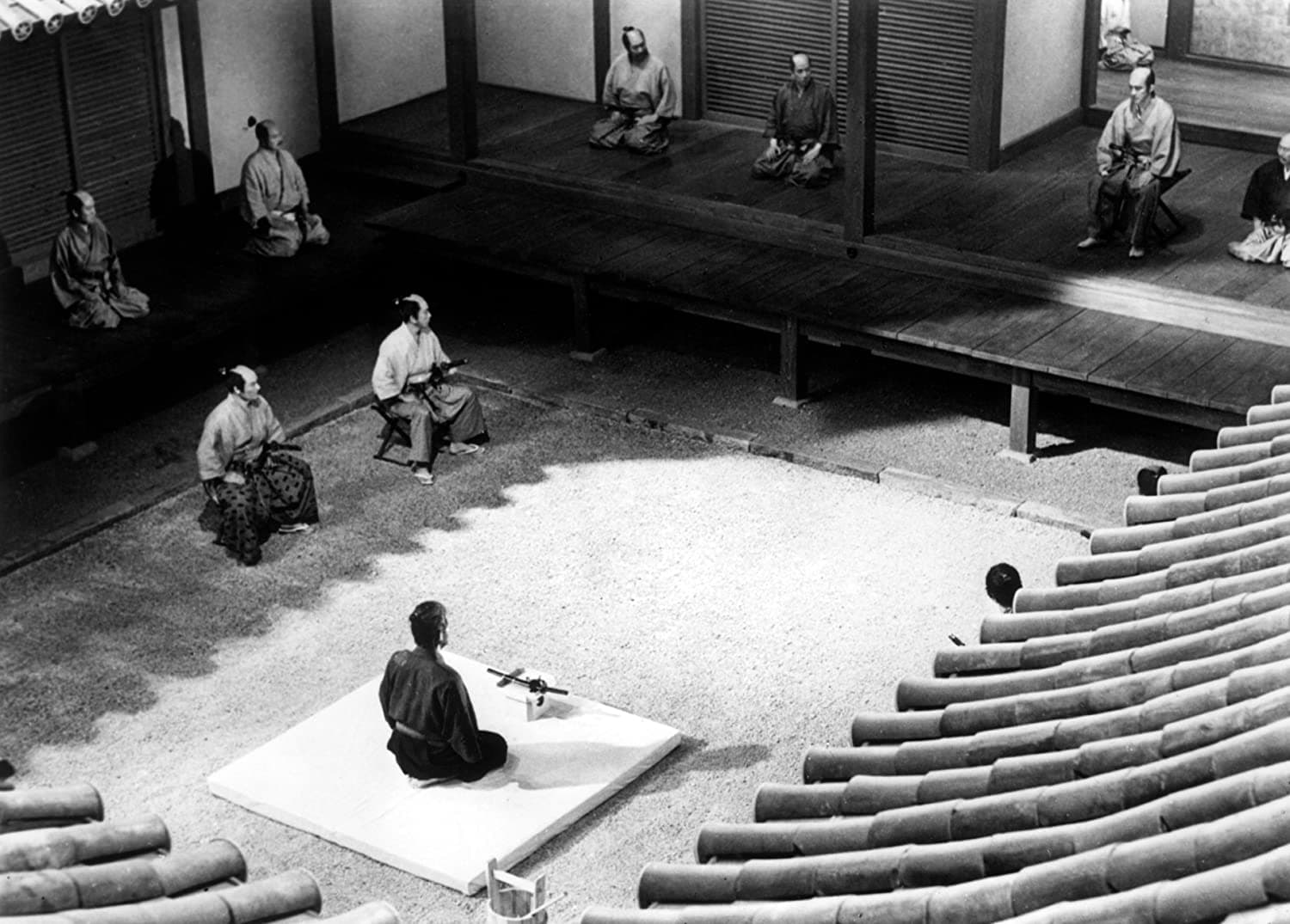

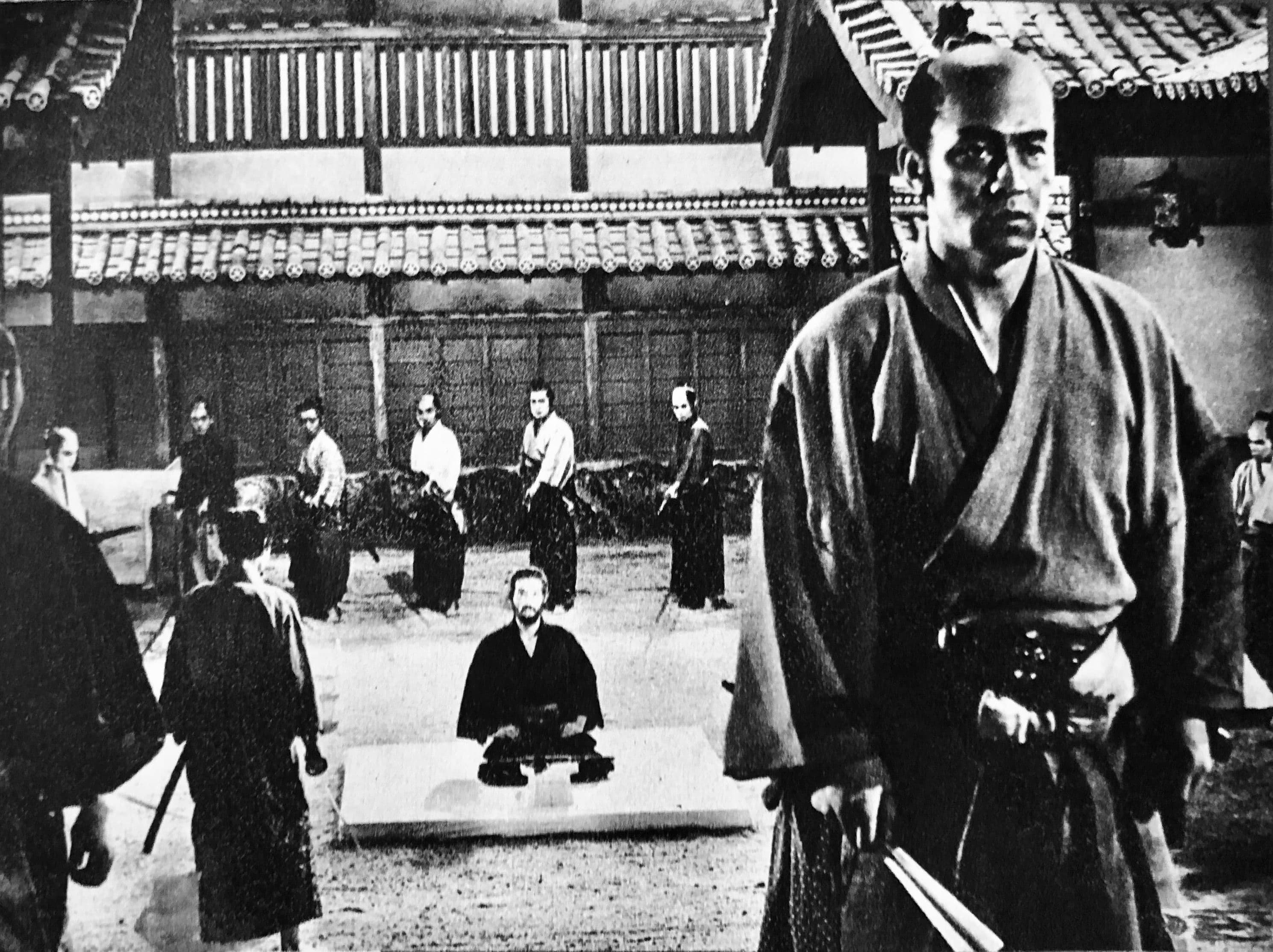

The narrative structure of the film is a diabolically perfect clockwork mechanism. When a ronin, the elderly and dignified Hanshirō Tsugumo (a monumental Tatsuya Nakadai), arrives at the palace of the Iyi clan to request an honorable place to perform seppuku, he is greeted with contempt and suspicion. To dissuade him, the clan's steward recounts, with ill-concealed satisfaction, the “pathetic” story of another ronin, the young Motome Chijiiwa, who had made the same request shortly before. Through a long flashback, we witness Motome's brutal and humiliating suicide, forced to disembowel himself with a bamboo blade because he had sold his real swords to feed his family. This story, in the steward's intentions, is meant to be a warning, but instead becomes the prologue to Tsugumo's revenge. Through a series of subsequent flashbacks, he reveals how their pasts are intertwined—Motome was his brother-in-law—and, in doing so, he not only challenges the integrity of the clan, but dismantles it piece by piece, exposing its empty and cowardly cruelty. The film thus becomes a powerful dialectic between official history, written by the powerful to preserve appearances, and personal truth, shouted out by the pain of the oppressed.

The figure of the ronin, the masterless samurai, is a fascinating element, and this film definitively demystifies it. While in Kurosawa's cinema and its countless Western imitators, the ronin is often an archetype of freedom, a knight errant who sells his sword to the highest bidder, here he becomes a symbol of economic precariousness and systemic failure. The peace of the Edo period, which forms the backdrop to the story, has made warriors a socially useless class, men trained only to fight in a world that no longer needs them. Tsugumo and Motome are not fallen heroes, they are desperate unemployed men, victims of a system that venerates them in the abstract but leaves them to starve in reality. Their request for seppuku is not an act of pride, but an extreme, tragic form of blackmail to obtain some money, a plea disguised as an honorable gesture.

Although Kobayashi's style is unique in its almost geometric rigor, elements of contact with other great masters of Japanese cinema can be found. Although far from his aesthetic, the film shares with Kenji Mizoguchi a profound and painful critique of oppressive social structures. Just as Mizoguchi recounted the tragic fate of women crushed by the rules of feudal society (think of The Life of Oharu), Kobayashi applies the same critical lens to the samurai class, showing how the code of honor becomes a deadly prison. Even more oblique, but perceptible, is the link with Yasujirō Ozu. It seems paradoxical, but Kobayashi's formal precision, his symmetrical, almost architectural compositions, and his tightly controlled staging are reminiscent of Ozu's visual discipline. Kobayashi, however, takes that formal rigor and empties it of all warmth, filling it with a cold tension and a looming threat. He uses Ozu's geometry to construct not a house, but a trap.

The ending is one of the most cynical and powerful conclusions in the history of cinema. After Tsugumo's bloody explosion of violence, the clan's official chronicle records his death and that of the other samurai as due to “illness.” The clan's symbolic armor, which had been desecrated, is returned to its place. The facade is saved, honor is restored, the truth is buried. With this final gesture, Kobayashi tells us not only that honor without humanity is barbarism, but that history itself is often just the version of events told by the executioners.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...