Harold and Maude

1971

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Hal Ashby is the director of this bizarre, irreverent, ironic film to its core. An atypical filmmaker, Ashby was an emblematic figure of the "New Hollywood" that dared to challenge conventions, forging a profoundly human cinema often tinged with a subtle melancholy. His direction in "Harold and Maude" is an exercise in lightness and depth, capable of dancing between the grotesque and the moving without ever lapsing into sentimentality or didacticism. He orchestrates a ballet between life and death, conformity and freedom, with a sensibility that we find in later works like the disarming "Being There" or the incisive "Shampoo," consolidating his reputation as an author capable of reading the American soul with an acute and never judgmental gaze.

The love story between two unlikely characters becomes the backdrop for their minimalist and surreal adventures. But this is not a simple love story; it is rather a hymn to life that manifests through the most unusual of mentorships. Ashby uses the age disparity not as a sensationalistic ploy, but as a magnifying glass to explore the nature of affection, mutual understanding, and liberation from social cages. Their "adventures" are vignettes of daily rebellion, escapes from banality, where the minimalism of the actions – a walk in the cemetery, a tree theft – is charged with an immeasurable existential meaning, almost reflecting the poetics of the absurd that permeated certain post-war European theatre.

The actions unfold with a terrifying naturalness and a sense of the grotesque that shines through like a watermark. "Terrifying" because the film does not shy away from the macabre; it embraces it, dissects it with an almost childlike candor, transforming the taboo of death and suicide into an art form, or at least, into a bizarre self-expression for Harold. The grotesque here is not a mere comedic license, but a true hermeneutical tool, a filter through which to decode bourgeois hypocrisy and social conventions. The sequence of Harold's "fake deaths," increasingly elaborate and theatrical, is a satirical indictment of the typical American family, too absorbed in its own narcissism to notice the cry for help, or perhaps, the son's mere need for attention.

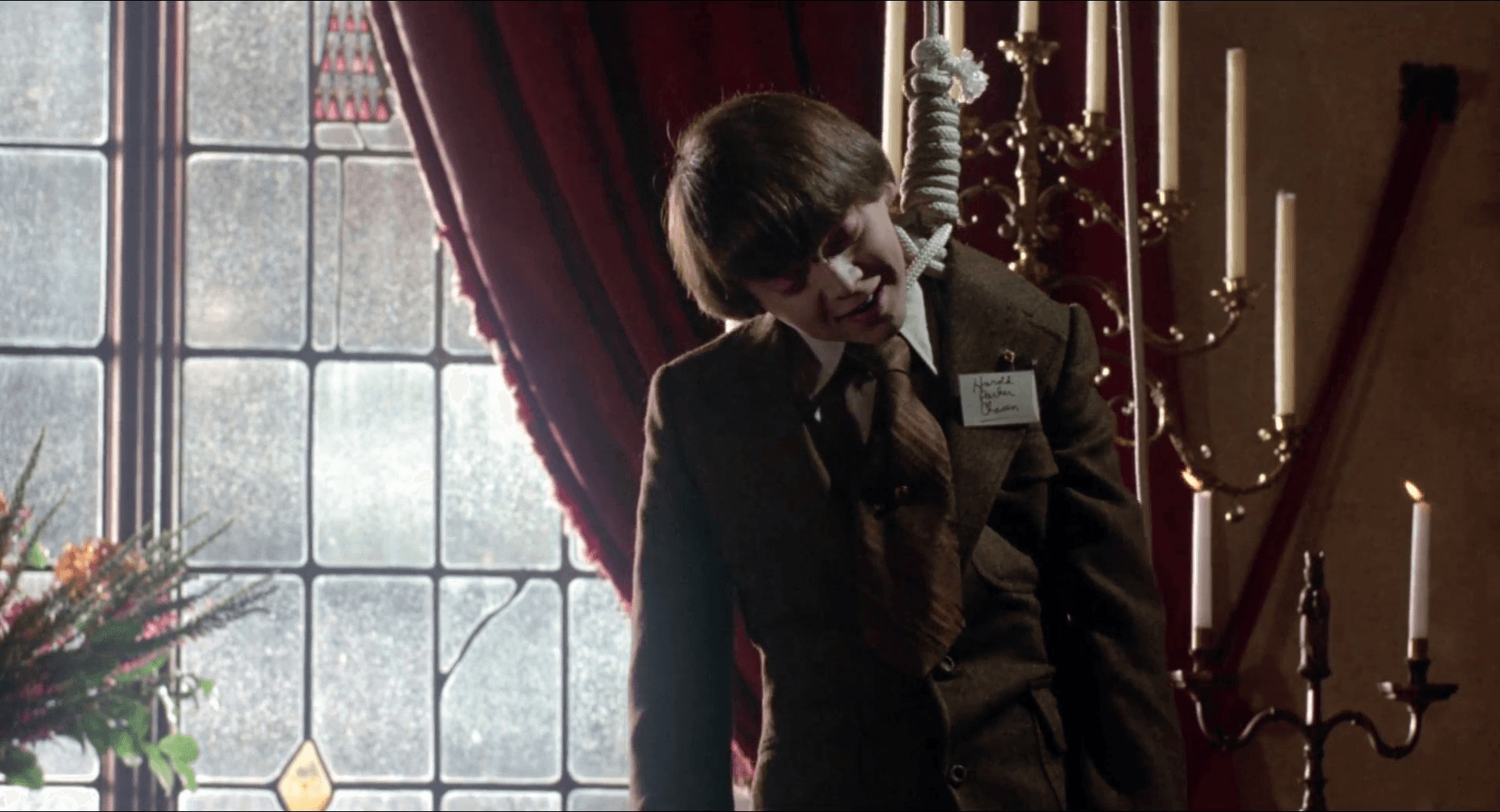

Harold is an eighteen-year-old depressed and weary of life; his only pastime is attending strangers' funerals. Maude is a spry seventy-nine-year-old in love with life, nonconformist and reckless on her motorcycle. Harold, portrayed by a Bud Cort of almost ethereal fragility, is the embodiment of a disillusioned youth, emptied of meaning in a world that seems to have lost all direction after the ideals of '68. His fixation on death is not nihilism, but a desperate search for authenticity in an existence he perceives as an endless performance. Maude, on the other hand, is an explosion of life, an anarchic and luminous force of nature, a kind of self-taught philosopher who has managed to make existence an art form. Ruth Gordon portrays her with contagious vitality, bringing to the screen the very essence of her career, made up of characters with strong personalities and an unshakeable charm. Her past, only hinted at through the concentration camp tattoo, adds an unsuspected depth to her carpe diem, transforming her joy of living into a form of resilience, an act of supreme rebellion against the suffering she endured.

When the two meet, it will be great love, and as soon as Harold announces to his family that he intends to marry Maude, an inevitable pandemonium will break out. This "love" transcends categories; it is not so much romantic as vital, an alchemy that leads Harold to rediscover the colors of the world. The family pandemonium, with Harold's mother's desperate maneuvers to "normalize" him through encounters with obtuse psychiatrists and improbable blind dates, is a biting satire on the conventional mindset, on the fear of the different, on the obsession with appearances. The family institution, as well as the Church and the Army (other "institutions" satirized in the film), are presented as suffocating entities, incapable of understanding or accepting what deviates from their strict norms.

Maude then makes it her concern to infuse all her love for life into Harold before she leaves him. Her lesson is not only about living, but also about dying. Maude's final choice, made with full awareness and serenity, is not an act of surrender, but the ultimate affirmation of her freedom and control over her own existence. It is the culmination of a life fully lived, to the last breath, and a lesson for Harold on the cyclical nature of existence, on the necessity of accepting pain and loss as an integral part of the beauty of living. The ending, with Harold dancing atop a cliff with the banjo given to him by Maude, is a moment of pure liberation, the echo of a profound transformation, of a soul finally freed from its chains.

Ruth Gordon and Bud Cort, both with extensive theatrical experience, are the performers in this comedy with grotesque and delightfully surreal tones, lending the story a highly appreciable touch of disenchantment. Their chemistry is palpable, a duet that elevates itself above the screenplay, imbuing the characters with an authenticity that makes even the absurd credible. Ruth Gordon's performance, in particular, is a masterpiece of vitality and wisdom, which earned her a Golden Globe nomination and cemented her fame as a pop and anti-conventional icon. The soundtrack, woven with the melancholic and subversive melodies of Cat Stevens, is not a mere accompaniment, but a true narrative voice that blends perfectly with the film's spirit, accentuating its bittersweet nature and its message of hope and rebellion. Songs like "Trouble," "Where Do The Children Play?" and especially "If You Want To Sing Out, Sing Out" become an integral part of the film's identity, hymns to individual freedom and the search for one's own voice.

A film that remains in the heart like a small discovery to be kept secret, but which, over the years, has managed to emerge from its initial semi-obscurity to establish itself as a true cult classic. Initially met with indifference or perplexity by critics and audiences, "Harold and Maude" became a cult phenomenon, screened continuously for years in art house cinemas and rediscovered by generations of viewers fascinated by its timeless originality. It is a modern fable, a manifesto of independence, and a constant reminder that life, with all its absurdities and its inevitable conclusions, is a precious gift to be celebrated and not feared, to be lived with the intensity and lightness of a dance on the edge of a precipice.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...