Children of Men

2006

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Alfonso Cuarón, together with Alejandro Iñárritu and the brilliant Guillermo del Toro – the holy trinity of talents that has redefined Mexican cinematic identity – is part of the nouvelle vague that has managed to infuse new life into auteur cinema, winning over proselytes among cinephiles worldwide and elevating visual storytelling to new heights. This renaissance, deeply rooted in a humanism that does not fear confronting the darkness of existence, manifests in Cuarón with a technical mastery and thematic depth that make him unique.

His work for the creation of this film was of the highest level, a tour de force that consecrated his vision, so much so that the film garnered numerous awards worldwide: from the prestigious British Academy Film Award for Best Cinematography, to BAFTAs for Best Editing, and the Osella Award in Venice for Best Cinematography, an unequivocal sign of its visual and narrative impact.

Children of Men is a story set in a not-too-distant dystopian future (2027 in the film, not 2022, a detail that makes its premonition even more chilling when considering current migratory and social crises), based on a 1992 novel by writer P.D. James. The choice of such a near future is not accidental: it amplifies the sense of urgency and makes the dystopia not a distant fantasy, but a bleak projection of our most recondite anxieties. The film stands out for its dark and oppressive atmospheres, landscapes of a post-atomic gray where the lack of light is a constant, but not only. It is a dystopia that lurks in the ordinary, in urban decay and the daily despair that pervades every single frame.

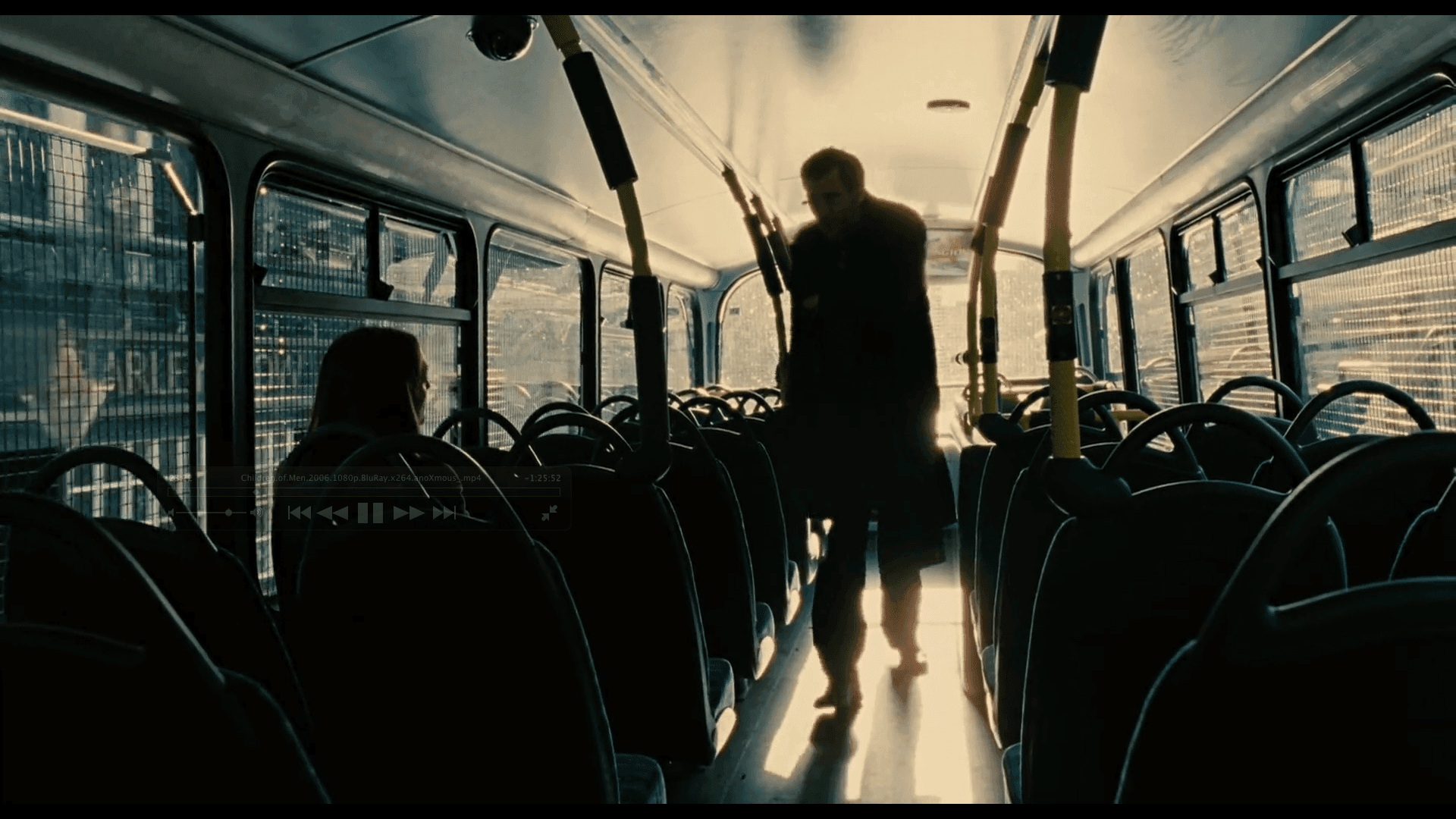

The cinematography by Emmanuel Lubezki, one of Cuarón's most trusted collaborators and an undisputed master in the use of natural light and long takes, is indeed one of the film's most striking elements. It is not simply beautiful cinematography; it is entirely complementary to the narration, a true mute character that amplifies the agonizing sense of oppression experienced by the protagonists. Lubezki, with his unmistakable palette of muted colors and a predilection for natural or scarce light sources, creates a world where hope itself seems a denied luxury, a visual echo of the sterility afflicting humanity. One might think of the influence of Flemish masters or Caravaggio in their ability to shape reality through the contrast between light and shadow, but here applied to a raw and unfiltered modernity. The world of Children of Men is a chiaroscuro painting, where every glimmer of light takes on the weight of a miracle, almost an act of rebellion against the prevailing darkness.

The story is one of an announced disappearance: humanity is destined to die due to infertility that has affected every woman on the planet. All women have, in fact, long since become sterile due to a mysterious plague that has rapidly spread across the globe and caused the total disappearance of children. Humanity is thus destined to eclipse itself, and the governments of various countries have taken drastic measures against the collective psychosis of extinction, implementing martial law and strict controls, militarizing society and transforming every border into an impregnable fortress for the "fugees," the desperate seeking refuge in an isolated but equally agonizing Great Britain. This vision of a Europe torn by migratory crises and brutal repression, with refugee camps reminiscent of the worst Orwellian nightmares, is not merely a framing element; it is the beating heart of a social critique that resonates with deafening topicality, far beyond its production date.

But a new hope appears on the horizon: a woman has become pregnant, and it will be up to a human rights activist, Theo Faron (portrayed with disarming and bitter humanity by Clive Owen), to transport her safely to a new freedom, out from under the oppressive yoke of the Government. Their journey will be a perilous voyage through a nation where violence and subjugation are the two elements governing the social fabric, a modern odyssey that evokes echoes of picaresque novels and religious allegories, where salvation is not guaranteed but is a desperate undertaking, permeated by an intrinsic faith in the redemptive power of life.

Memorable is the scene in which the activists are transporting the woman to a safe place and are suddenly attacked by a band of savage men who emerge from the surrounding woods. Here Cuarón and Lubezki reach the pinnacle of their technical and narrative mastery. A marvelous long take begins, documenting the violent attack, a macabre ballet of camera and choreography that extends for over four minutes, immersing the viewer directly in the chaos and brutality of the assault. The camera follows the action with an almost subjective emphasis, moving inside the car and framing now the interior, now the exterior, but always remaining inside the passenger compartment as if it were one of the occupants, a helpless and terrified witness. This stylistic choice eliminates any sense of detachment, forcing the audience to confront the raw, relentless reality of the violence. When one of the women traveling in the car is shot in the neck, the sequence becomes chilling in its crude realism; the shot nervously transitions over the distraught faces of the group members to that of the dying woman's diaphanous face, in an almost unbearable agony.

This is not a mere technical display; it is a declaration of intent. Cuarón uses the long take not to astound, but to saturate the viewer with a totalizing sensory and emotional experience, to convey the terror and vulnerability of the characters in real-time, without the artifice of editing to break the tension. It is a technique that the director has perfected, from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban to Gravity and Roma, but which here achieves an almost unprecedented visceral quality, making every breath, every shot, every scream a blow to the viewer's heart. The car ambush scene is just a taste of the greatness that characterizes the entire film, culminating in the celebrated battle sequence in the refugee camp, a long take of over six minutes that is a true masterpiece of coordination and immersion in wartime chaos, an experience that goes beyond mere entertainment to become a profound inquiry into human resilience and despair. Children of Men is not just a dystopian science fiction film; it is a work of art that speaks of our present, a disturbing warning and, paradoxically, an anthem to fragile, indomitable hope.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...