Days of Heaven

1978

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Terence Malick, a great master of cinematic aesthetics, writes and directs a work that delves into the characters' feelings, exposing them to the viewer like precious treasures finally brought to light. It is not a mere psychological exploration, but rather a true lyrical epic that elevates human intimacy to universal drama, forcefully embedding itself in the vein of Malick's filmography, which has always been devoted to the search for transcendent truth in the everyday, in the imperceptible pulse of nature, and in the silent echo of souls. His cinema, built more on suggestion than explanation, on interior monologues that dance between the poetic and the philosophical, finds one of its supreme expressions in this film.

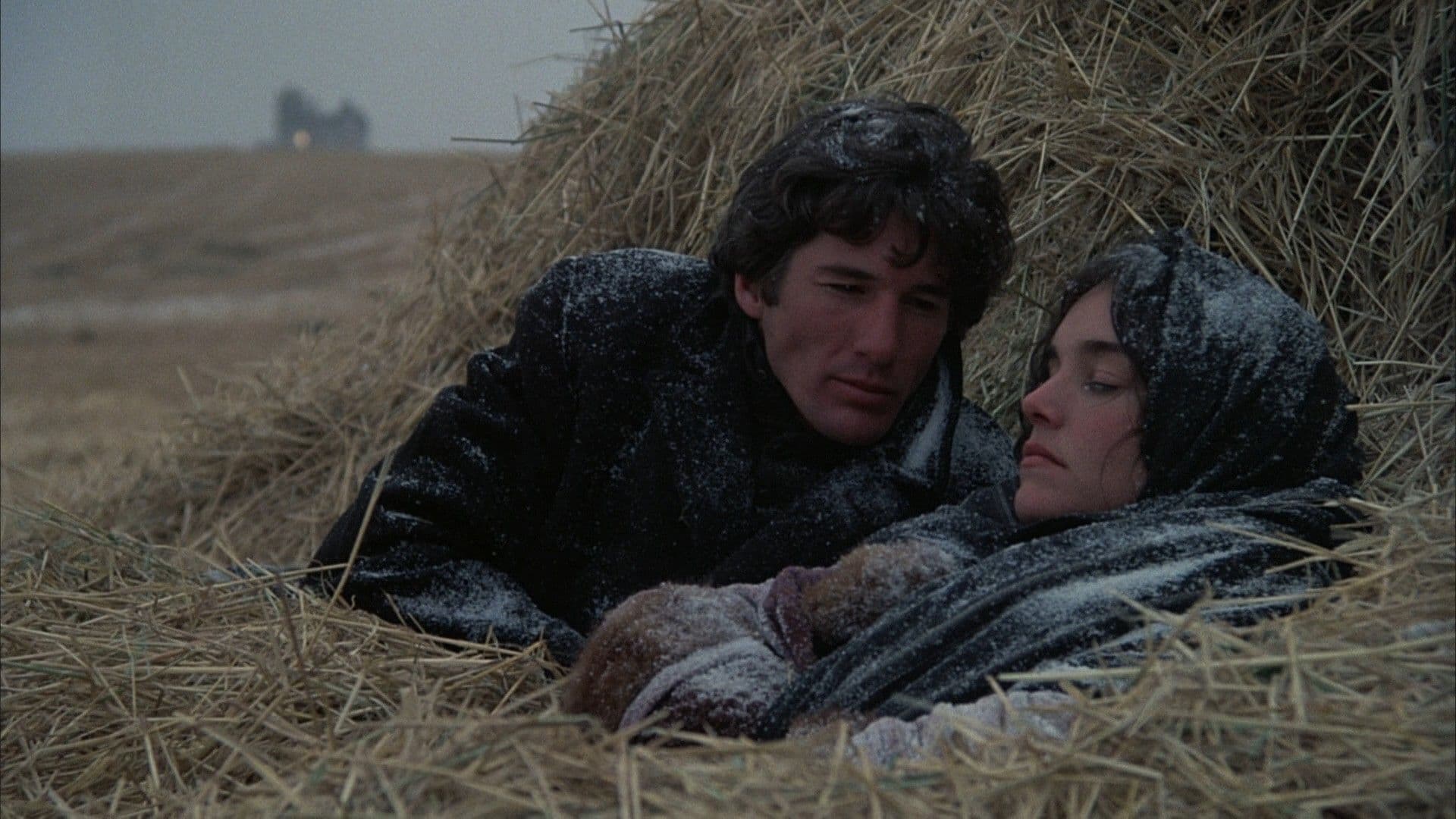

The story is that of Bill (Richard Gere) and Abby (Brooke Adams), a pair of lovers who pretend to be brother and sister, a stratagem dictated by desperation and the need for survival in a ruthless world. From ruthless Chicago, where they cannot survive, an emblem of modernity that devours the humble, they move south, towards Texas, a vast and primordial land that promises, illusorily, a new genesis. They are accompanied by Linda, Bill's younger sister, the story's narrator, whose voice-over, at once naive and sagacious, innocent and premonitory, serves as a Greek chorus, filtering the tragedy through the detached yet acute lens of childhood. It is through her eyes that the story takes on the hues of a raw fable, of a rustic myth that unfolds in all its inevitability.

They arrive at a farm, an oasis of prosperity in a desert of poverty, and begin working as laborers, immersing themselves in a rural rhythm of life that is both harsh and idyllic. Until Chuck, the terminally ill farm owner, falls in love with Abby: Bill, having learned of the illness and driven by the blind ambition to escape destitution, urges Abby to marry him for money. A decision that seals a pact with the devil, laying the groundwork for a moral abyss. Once married, Bill realizes that Abby is falling in love with Chuck, a sentimental complication that triggers the true detonator of the plot, revealing the fragility of their intentions and the unstoppable power of the heart. Thus begins a storm of emotions, a vortex of jealousy, desire, and betrayal that will consume all the protagonists, leading them towards an ending as inevitable as it is heartbreaking.

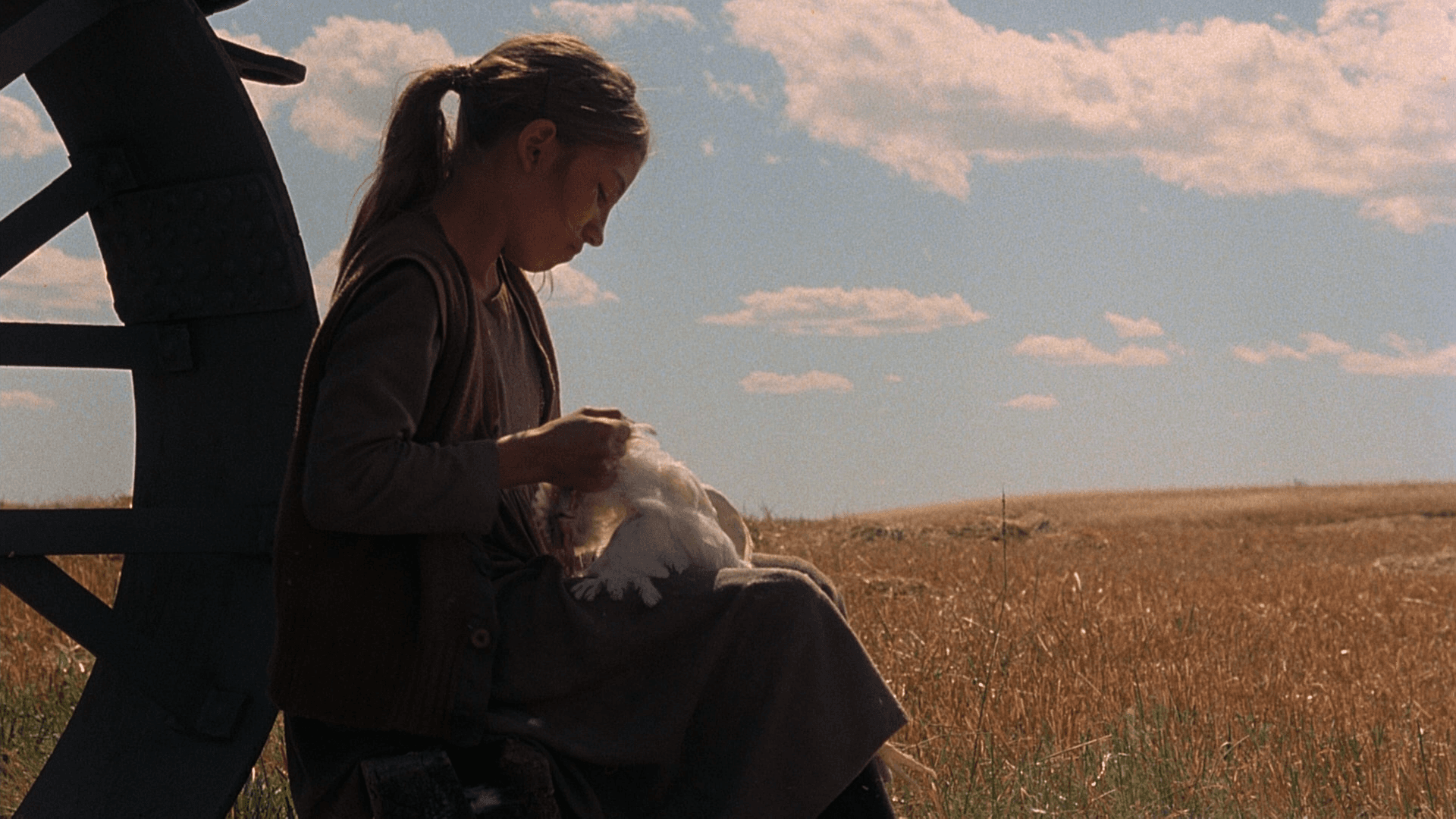

This is a plot with Shakespearean overtones, where primal passions clash with social conventions and fate weaves its relentless web. Malick moves his characters towards tragedy with narrative fury, orchestrating a drama of epic proportions in a rural microcosm. Such fury is corroborated, indeed enhanced, by Nestor Almendros' superb cinematography, a masterpiece of aesthetics and technique that earned him a well-deserved Oscar. The choice to shoot almost exclusively during the so-called 'magic hour' – the brief period at dawn and dusk when light is golden and diffused – is not merely a pursuit of pictorial beauty, but a true visual philosophy. This ethereal, almost unrealistic light imbues the scenes with a dreamy and melancholic aura, elevating each frame to an Impressionistic, sometimes Expressionistic, painting, where nature is not a mere backdrop but an active protagonist, a mirror of the characters' souls and a premonition of events. The texture of the images, the saturated yet natural colors, the sensation of a vital breath permeating every shot, are the result of meticulous attention to detail and a profound understanding between director and cinematographer, capable of capturing the very essence of light. One perceives a quest for visual authenticity that moves away from traditional lenses and filters, opting for an almost documentary-like rendering of natural light, yet the result is one of sublime and adamantine stylization.

The rural landscape of South Texas becomes a polished narrative instrument, an almost living entity that interacts with the characters, reflecting their moods and foreshadowing their destiny. The endless wheat fields, isolated houses, and boundless sky are elements that contribute to creating a sense of isolation, of existential solitude, but also of primordial grandeur. Frames that resemble paintings, yes, but not only that – true moving canvases where the perfect light, which bathes stylistically adamantine images, is not a mere embellishment but a vehicle of meaning. The scene of the locust invasion, biblical in its scope, and the fire that devastates the fields, a symbol of purification and destruction, are not special effects, but moments of pure visual epiphany that cement the indissoluble link between man and nature, between human desire and the uncontrollable forces of the cosmos.

A work of extraordinary psychological depth, therefore, but one that eschews didactic psychology, preferring allusion, the unsaid, the whisper. It is a ruthless observatory for dissecting the stirrings of the soul, but it does so with the delicacy of a poet and the acumen of a philosopher. Malick invites us to contemplate the misery and grandeur of man, his capacity to love and to destroy, his perennial search for a place in the world. "Days of Heaven" is not just a film; it is a sensory and intellectual experience, a hymn to the ephemeral beauty of the world and the fragility of the human condition, a masterpiece that continues to shine like a beacon in the history of cinema.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...