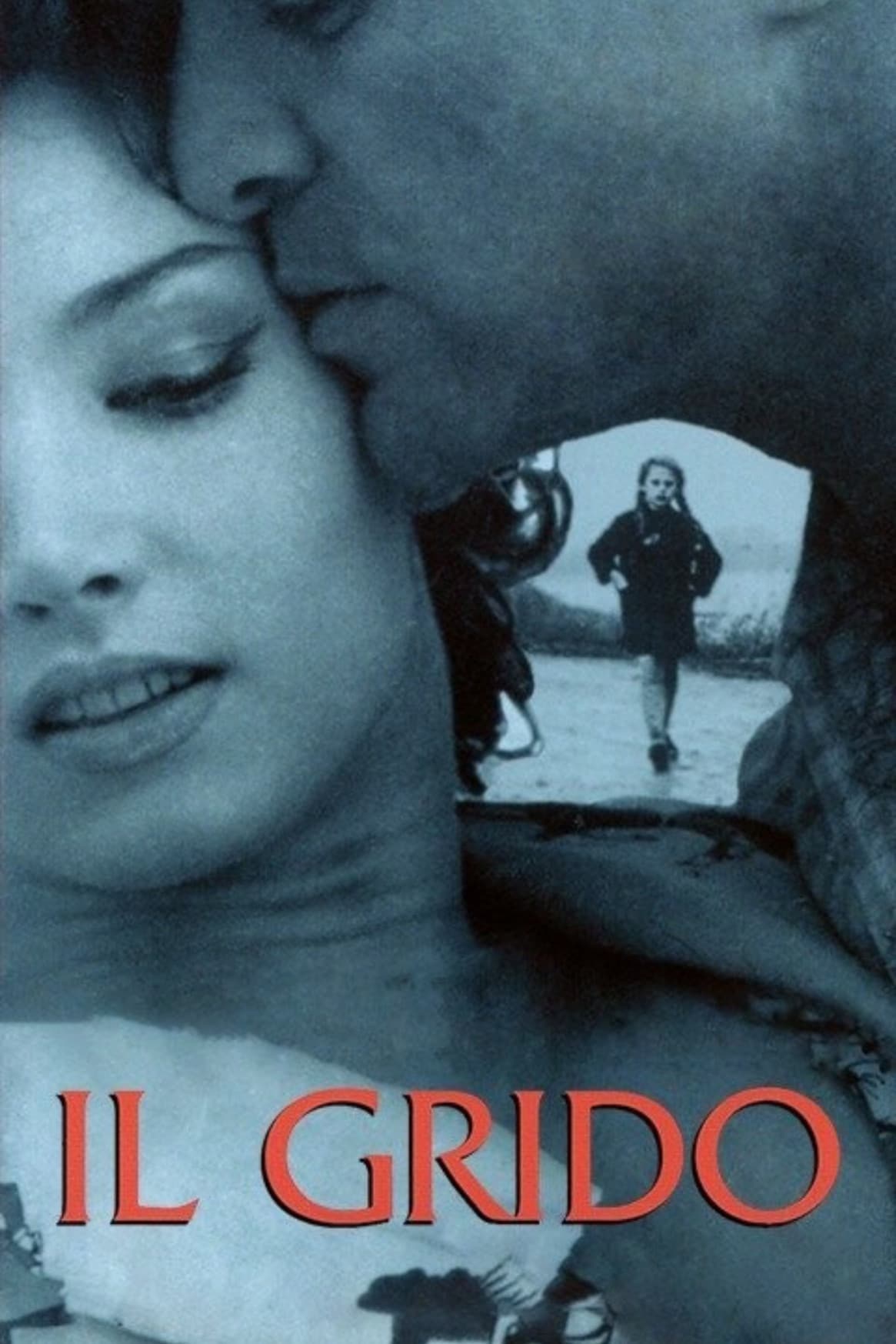

Il Grido

1957

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A painful message of incommunicability, this could be the ultimate synthesis of this fascinating work by Michelangelo Antonioni, a film that, though often overshadowed by the fame of his subsequent "trilogy of alienation" (L'Avventura, La Notte, L'Eclisse), represents an indispensable matrix for them, almost a premonition. "Il Grido" (The Cry) is the crucible in which the Ferrara-born director refines his gaze upon existential void, on the difficulty of connecting in a world that seems to have lost its moral and emotional compass, a theme that would become the unmistakable stylistic hallmark of his cinema.

The director entrusts a journey with the mystifying experience of the protagonist's emotional marginalization, and through his eyes, reworks a hostile provincial landscape, unknowable through the litmus test of a failed love. It is not a mere backdrop, but a silent interlocutor, a co-protagonist in flesh and blood, or rather, in earth and fog. The Po Valley, with its infinite horizons and desolate settlements, becomes a map of Aldo's soul, an external projection of his inner disorientation.

The story revolves around the journey of a man, Aldo, played by Steve Cochran, whose rugged physicality and perpetually furrowed expression perfectly embody the archetype of the man in crisis, and his young daughter, Rosina, through the Po Valley region. This itinerary, crossing an Italy still marked by the scars of the post-war period, but already moving towards a dehumanizing modernism, is less a flight and more an erratic wandering, devoid of destination or true direction, save that dictated by the impulse of the moment. Rosina is the only apparent anchor, a fragile link to a lost normality, but she too is destined to be scattered in the whirlwind of paternal alienation.

The man has left home after arguing with his partner Irma, who has left him for another, and seeks through movement a kind of catharsis, an attempt at redemption. But his is a futile quest, doomed from the start. Aldo, a refinery worker, is a relic of a vanishing patriarchal world, incapable of processing the grief of loss and accepting rejection. His "cry" is suffocated not only by incommunicability with others, but by his own inability to formulate a meaning or purpose, an echo of the existentialist themes that permeated European culture of the time, making the film a bridge between the neorealism of physical ruins and the modernism of spiritual ones.

But the people and places he encounters only serve to further distance him from reality, from emotions, and ultimately, from himself. Every encounter – with the women of his past, with marginal figures met on the road – offers no solace, but acts as an implacable mirror, reflecting his solitude. From Andreina, the kind-hearted prostitute, to Virginia, the gas station attendant, to Elvia, his former sister-in-law, each woman represents a missed opportunity, a fragment of a future he cannot or will not grasp. These are female figures who, even in their vulnerability, seem to possess a resilience and awareness absent in Aldo, who remains mired in his past, unable to move beyond.

A grand film about the unspoken word, about the past that gnaws at life, about human relationships reduced to zero, about the estrangement caused by a life of oppressive correlations. It is a bitter ode to the deafening silence that settles between individuals, to the inability to express the deepest feelings or to accept those of others. The past is not a memory from which to learn, but an inexorable ballast that drags Aldo into an abyss of despair. Human relationships, ephemeral and superficial, reset as soon as they begin, leaving a void that the presence of others cannot fill. The estrangement is not only psychological, but almost ontological, an existential condition in which the individual feels alien to himself and the surrounding world, an echo of the "malaise of living" Montale spoke of.

Antonioni, in this work, distills his minimalist and rigorous aesthetic. The camera moves with an almost hypnotic slowness, dwelling on faces, gestures, and especially, on those environmental details that acquire an almost metaphorical eloquence: a swamp that swallows the road, a solitary telephone pole, a bridge that leads nowhere. The visual composition is of almost pictorial precision, with shots that often favor long and wide shots, immersing the fragile protagonist in vast and indifferent landscapes. The soundscape is equally crucial: the rustle of the wind, the noise of machinery, the whistle of the train, merge into a symphony of alienation, often overpowering the rare and ineffective words spoken by the characters, thus amplifying the sense of solitude and incommunicability. It is the staging of a silent agony, where even the "cry" of the title is an implosion, a scream that finds no voice.

"Il Grido" (The Cry) represents a crucial moment in Italian cinema, marking a clear departure from the conventions of more orthodox neorealism, while retaining its preference for non-actors and authentic locations. Where neorealism sought hope, however faint, in social solidarity, Antonioni delves into the wounds of the individual soul, showing the emotional devastations of economic prosperity that does not translate into happiness or understanding. The film, presented at Cannes where it won the FIPRESCI Prize, was initially misunderstood by some critics, who found it too pessimistic or cryptic. Yet, precisely in this daring exploration of interiority and the abandonment of narrative certainties, lies its prophetic greatness, anticipating the anxieties of a society that would soon discover its own solitude at the heart of prosperity.

A work in which the surrounding environment is filmed with studied sharpness, a cleanliness that seems analogous to an inexhaustible pain, to an experience that mixes with the trees, rows, and fields of the Po Valley and dissolves into nothingness, an aphonic cry that emerges from the belly of the earth, extinguishing all hope. The final sequence, in which Aldo ascends the tower only to fall, is the apex of this fusion between man and his environment. It is not a heroic act, nor a liberating gesture, but the inevitable culmination of a path of self-dissolution. His body merging with the earth, his voice unheard, his existence nullified in the indifferent landscape, are the crudest and most definitive affirmation of Antonioni's message: incommunicability is not merely an obstacle, but an inescapable condition, a destiny in which every attempt to connect resonates as a deafening silence.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...