Pather Panchali

1955

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A veritable locus of beauty hinged upon a sharp social critique, a long cry of pain that subtly rises from the film and becomes a powerful means of communication with the West, revealing an unexpected sensibility and depth.

Thus one could summarise Satyajit Ray's first, dazzling film, the progenitor of the celebrated Apu Trilogy, a work that, with its disarming authenticity and stark lyricism, opened Western eyes wide not only to the immense cinematic potential of a nation freshly freed from the colonial yoke, but also to the richness of a millennial culture capable of expressing itself through a universal language. India, destined shortly to become the world's leading producer in the film industry, found in Ray its most sublime and rigorous bard, a director capable of distilling the essence of the human condition without ever indulging in didacticism or mannered exoticism. His debut, moreover, was an almost epic undertaking, funded intermittently by the Government of West Bengal, a production odyssey that reflected, on a smaller scale, the very resilience of the Indian people.

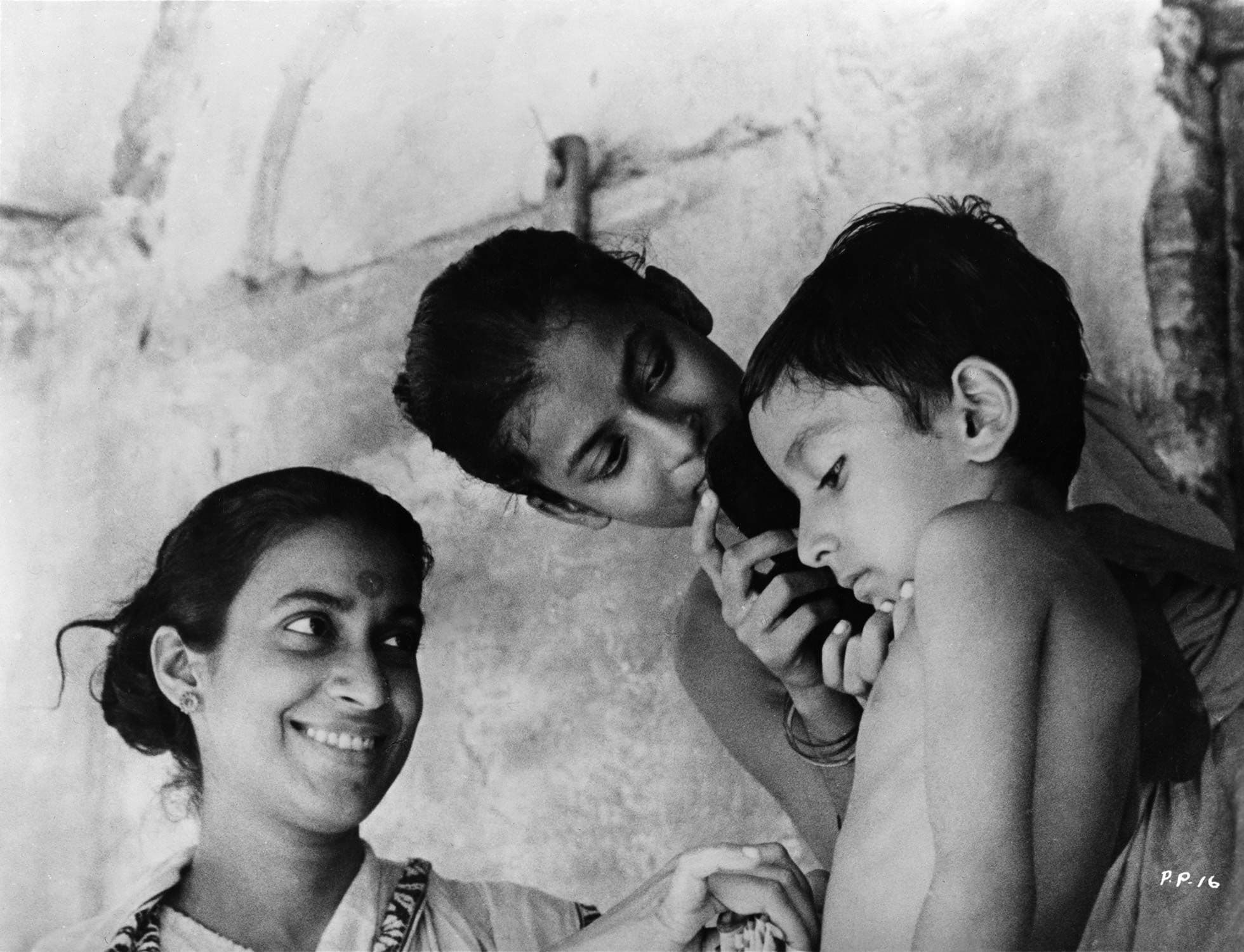

The story is, in its simplicity, paradigmatic: that of a peasant family in rural Bengal facing tremendous poverty and the merciless snares of fate through the filter of the gaze of its youngest member, young Apu. His perspective, unspoiled and curious, acts as a prism through which we perceive the microcosm of rural life, the ephemeral joys and cyclical tragedies, all without misery ever being exhibited as mere spectacle, but rather as an intrinsic component of daily life. It is in this subtle dialectic between childlike innocence and the implacable harshness of reality that the film's most acute social critique lies, one that does not point fingers but shows, with an almost anthropological delicacy, the resilience and fragility of lives on the margins.

The struggle against ineluctable events and misfortune vividly recalls Verga's I Malavoglia, bringing to mind that Verismo which, despite its different cultural iterations, shares with Ray's sensibility a deep adherence to life, the denunciation of the iron law of destiny and the stasis of a predetermined social condition. But where Verga relied on the epic narrative of the collapse of a patriarchal universe, Ray sculpts an impressionistic fresco, made of details and silences, which also evokes the atmospheres of Italian Neorealism, with which "Il Lamento sul Sentiero" shares not only the use of non-professional actors and a predilection for outdoor filming, but also a profound empathy for the dispossessed and a faith in humanity, even amidst the drama.

When the family, exhausted and struck by bereavement, decides to move to Benares to seek better fortune, the poignant farewell to nature, to childhood places and memories becomes an occasion for enchanting lyricism that never verges on pathos. Ray here elevates the gesture of departure to a pure art form, where the camera lingers on significant details – a frog jumping in a pond, a train cleaving the landscape, the rustle of wind through the reeds – transforming detachment into an almost transcendental experience. The train, in particular, is not merely a means of transport, but a powerful symbol of progress and escape, of an uncertain hope moving away from the stasis of a rural world condemned to suffering. This sequence is the quintessence of Ray's cinema: evocative without being didactic, profound without being pretentious.

Crucially contributing to this vision is the wonderful cinematography of Subrata Mitra, who, with his tastefully and originally filtered black and white, creates a timeless atmosphere. Mitra does not merely illuminate scenes; he sculpts light and shadow, transforming poverty into a canvas of meaningful contrasts. His shots, often static and wide, capture the vastness of the landscape and the smallness of man within it, lending dignity even to faces marked by toil. The use of innovative techniques for the era, such as natural light illumination to recreate raw reality, helped define an aesthetic that would become a beacon for generations of filmmakers, influencing art-house cinema far beyond Indian borders.

And finally, special mention must be made of the finely conceived and composed soundtrack by the legendary Ravi Shankar, in his first cinematic work. Using native instruments such as the sitar, bansuri, and tabla, Shankar weaves a sound tapestry that does not merely accompany, but defines and elevates the poignant narrative, framing it within a melancholic and contemplative mood. His melodies, steeped in traditional raags, merge with the images in a perfect synesthesia, communicating joy, loss, hope, and resignation without the need for words. It is music that breathes with the characters, a heartbeat that pulses in sync with the most recondite emotions, transforming the film into a visual and sonic symphony.

"Il Lamento sul Sentiero" is, ultimately, a moving, powerful, unsettling work in its truth and, even today, of staggering relevance. It was a cry of redemption for an emerging cinematography and a hymn to human dignity, a masterpiece that redefined the canons of world cinema, demonstrating that artistic greatness can emerge even from the most extreme simplicity and the deepest empathy.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...