The Servant

1963

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Losey, with the complicity of the great playwright Harold Pinter, creates a perfect narrative mechanism; not a mere dramatic cog, but a precision clock that measures the downfall, inexorably ticking towards a psychological implosion. Their artistic partnership, forged also by a shared outsider sensibility (Losey, a British exile due to McCarthyism, found an intellectual and spiritual ally in Pinter), manifests in an almost alchemical synergy. The Pinteresque, with its pauses laden with unspoken meaning, its seemingly anodyne dialogues that conceal abysses of latent threat, and the power dynamics underlying every interaction, finds its most acute and disturbing cinematic transposition in Losey's visual language.

One of those stories that transforms right under the spectator's nose, who can only succumb to its perverse allure while sinking into a kind of narrative trap set by the author. It is not merely a tale that evolves, but a metamorphosis in progress, an inexorable descent into the spiral of dependency and submission, where social and psychological hierarchies are systematically subverted with a sickly grace. The audience is not a mere observer, but rather an involuntary accomplice, trapped in an almost seductive morbidity, unable to tear their gaze away from the progressive crumbling of identities, as if it were a sociological experiment conducted in real time on the most vulnerable human soul.

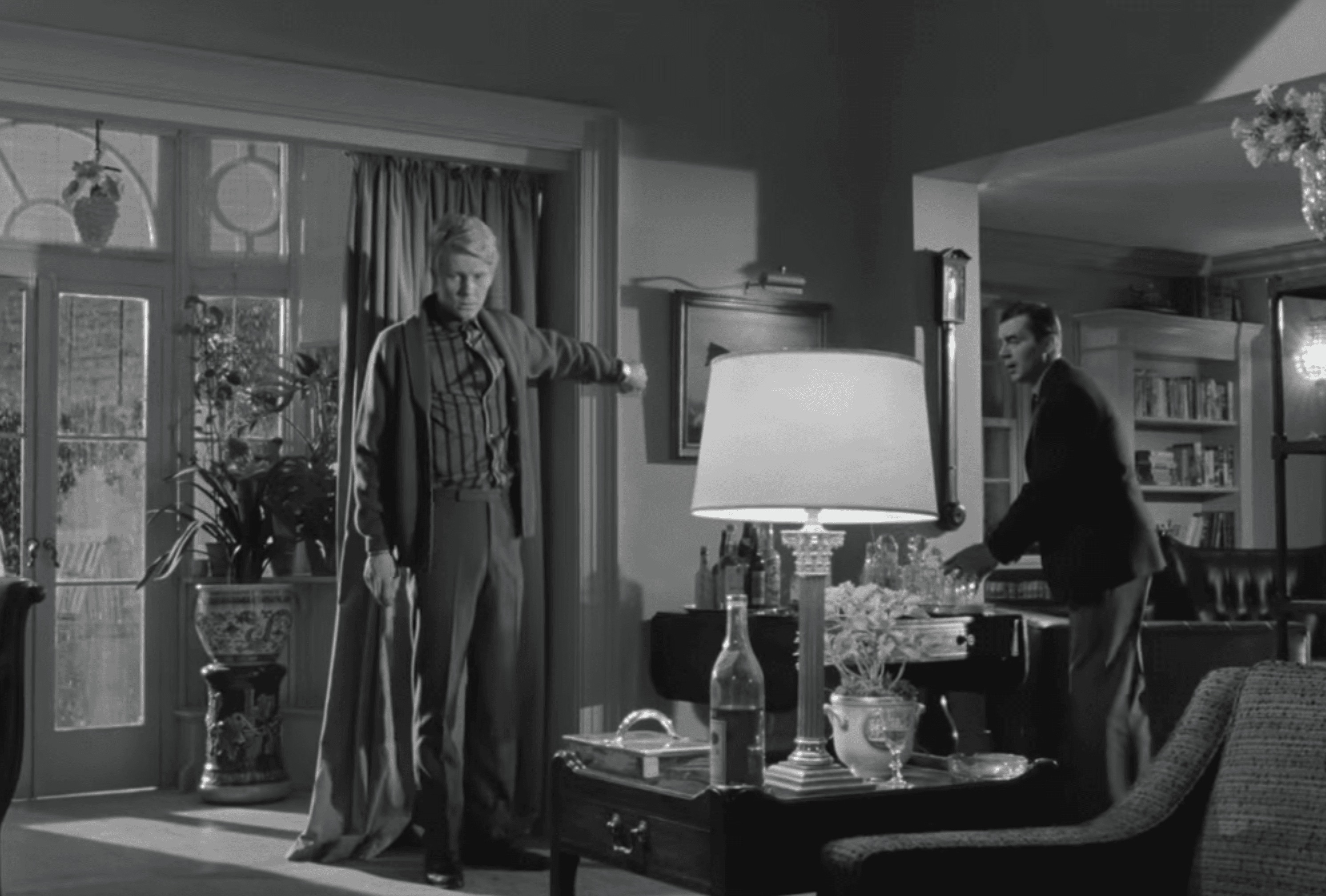

A wealthy and spoiled young man, Tony (a remarkable James Fox), moves to London and hires a servant, Barrett (a masterful Dirk Bogarde), to attend to his opulent possessions and his disordered life. Tony is the embodiment of a languid British bourgeois-aristocratic class, devoid of true will, clinging to the vestiges of a glorious past but incapable of facing the challenges of the present. Barrett, conversely, embodies a dark and pragmatic force, a new type of ambition that feeds on the weaknesses of others, a social parasite nestled in the heart of decadence.

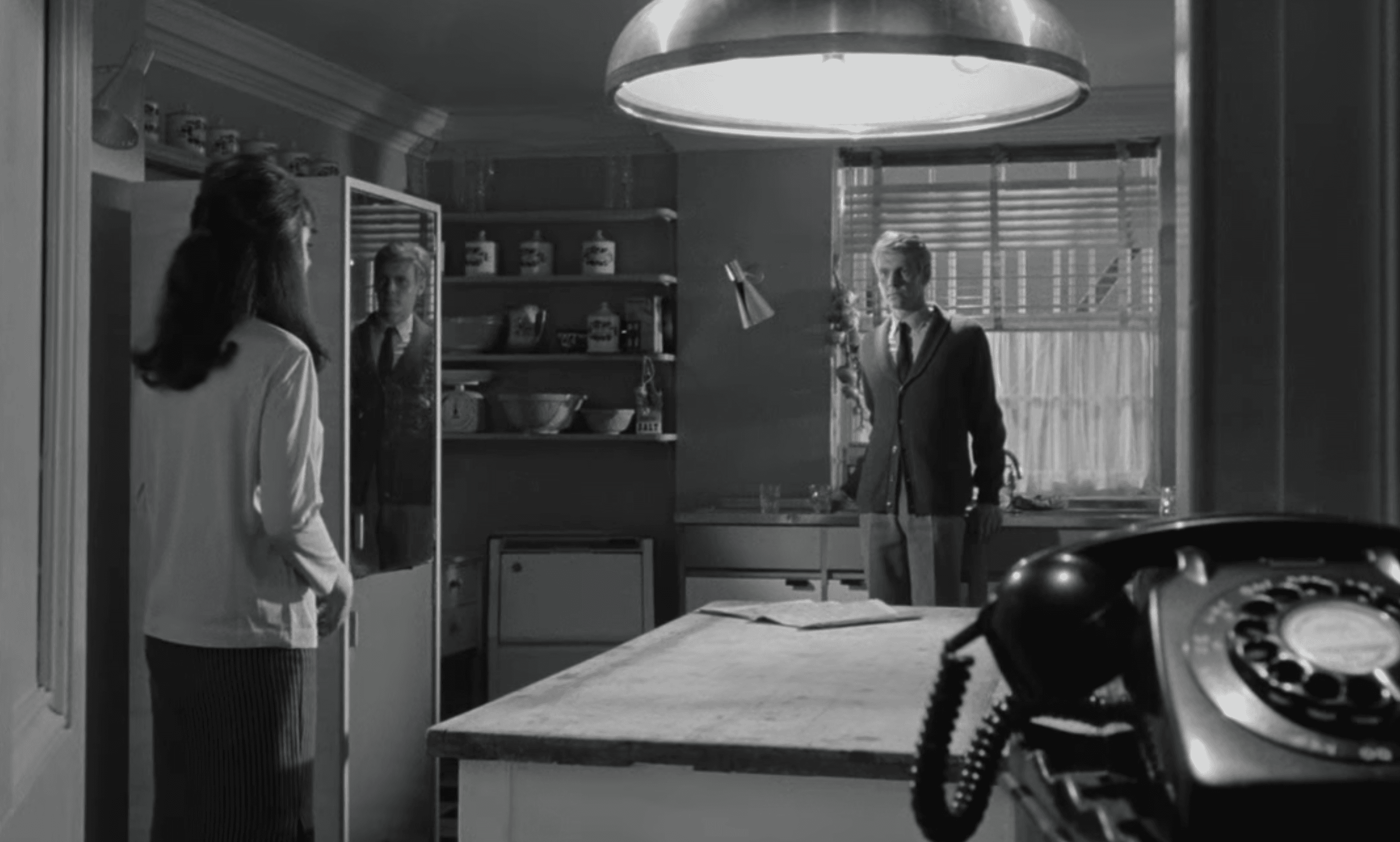

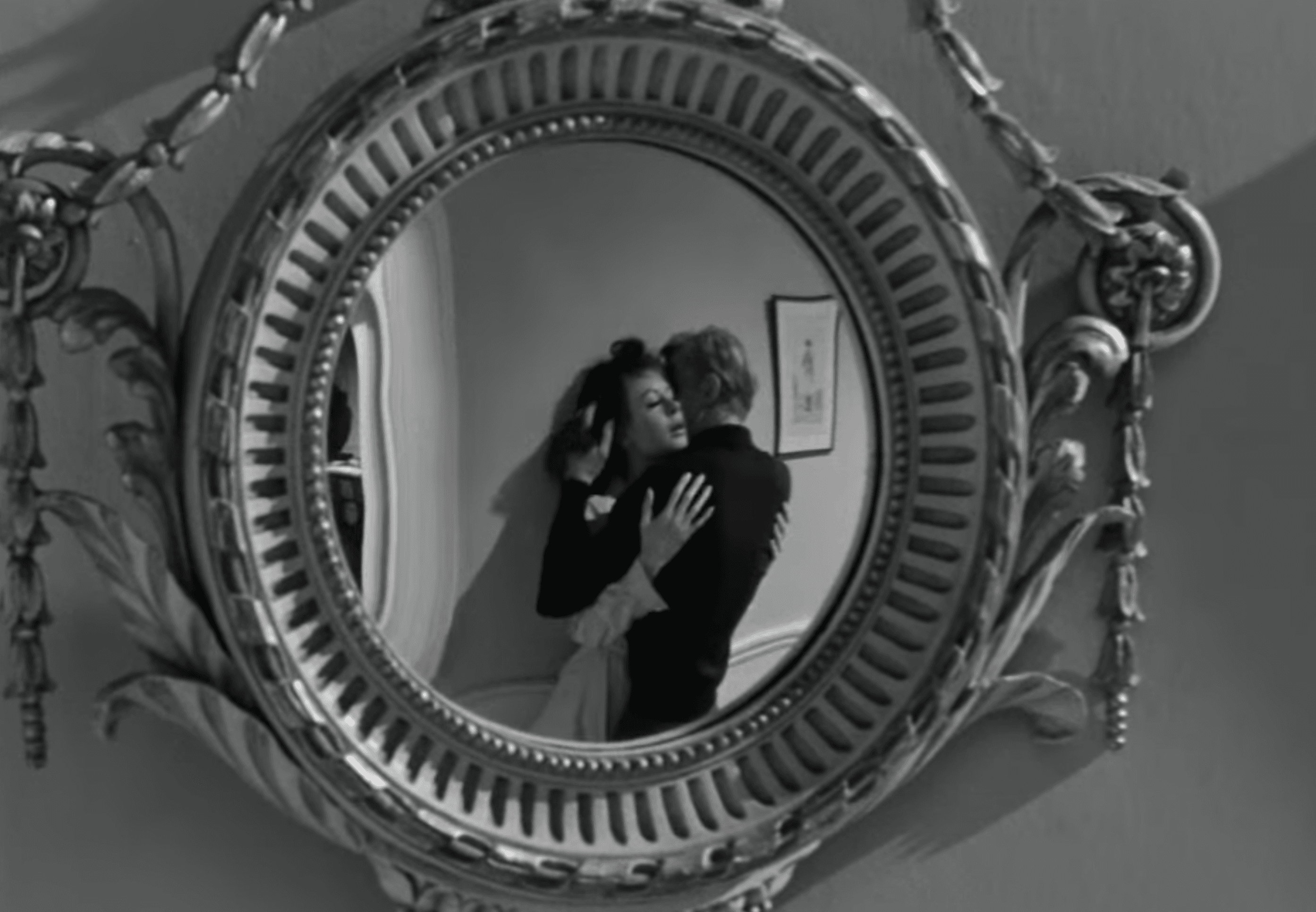

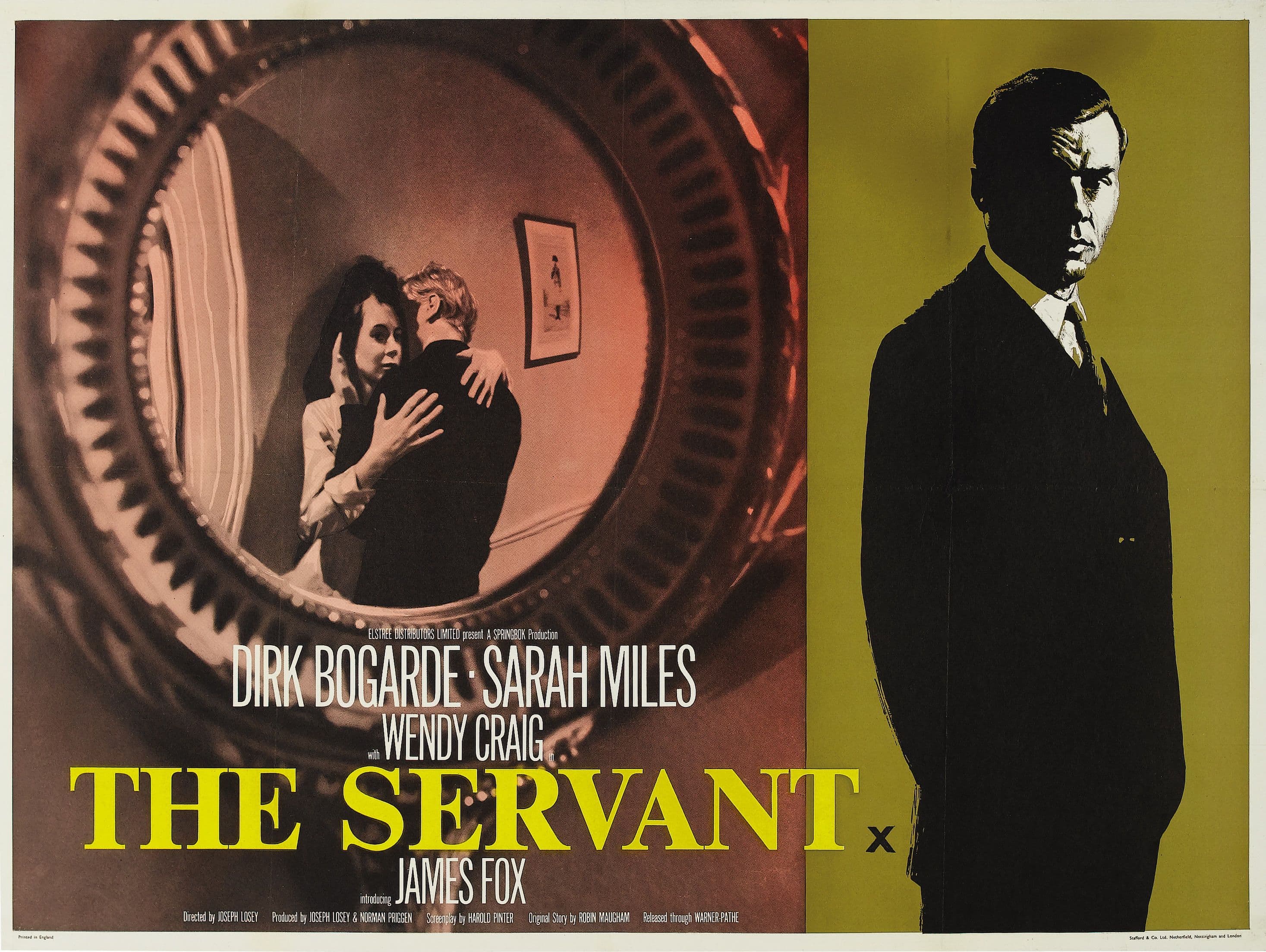

A strange relationship develops between the two, corrupted by the servant's tainted charisma, who will gradually become his employer's mental tormentor, disposing of his will and desires at will. It is here that the film unfolds its true nature as a social and psychological allegory. The bond between Tony and Barrett evolves from an initial master-servant dynamic to a disturbing role reversal, a methodical erosion of every personal and social boundary. Barrett, with a calculated series of micro-aggressions and silent manipulations – from the introduction of his "sister" Vera (Sarah Miles), a woman of dubious morality, to the subversion of the household's routines and habits – progressively undermines Tony's fragile masculinity and autonomy. Tony's fiancée, Susan (Wendy Craig), senses the threat and tries in vain to lead her partner back to a healthier reality, but her attempt is destined to fail in the face of Barrett's subtle and pervasive power, which exploits Tony's latent sexual ambiguity and emotional dependence. The house itself, initially a symbol of order and privilege, transforms under Losey's direction into a claustrophobic prison, a mental space where the walls close in and reflections in mirrors distort reality, trapping the characters in a labyrinth of repressed desire and destruction.

Losey's iconic filmmaking perfectly adheres to Pinter's brilliant dramatic dictate and succeeds in conveying its sepulchral flavor along with the psychological torment. Losey's direction is never invasive, but surgical, almost clinical in its observation. Through Douglas Slocombe's masterful black-and-white cinematography, the film bears an extraordinary visual density. The recurrent use of mirrors and reflective surfaces is not a mere stylistic flourish, but a narrative device that fragments identities, multiplies perspectives, and underscores duplicity and self-loss. Close-ups on the faces of Bogarde and Fox reveal an abyss of unspoken emotions, ancestral fears, and unspeakable desires. Bogarde, in particular, offers a performance that redefined his career, moving him away from "matinee idol" roles to embrace complex and morally ambiguous characters that made him an icon of European auteur cinema. His portrayal of Barrett is a tour de force of cold determination and ambiguous seduction, capable of transforming a smile into a menacing sneer and a gesture of service into an act of dominance.

A work by Losey that gradually reveals its diabolical implications, traveling into the minds of the protagonists yet remaining in perfect equilibrium with the world we know, experience, and touch, without indulging in dreamlike or pragmatically diluted aspects. Its strength lies precisely in this rooted adherence to reality, however distorted it may become. The terror does not stem from an external monster or a surreal nightmare, but from the internal corrosion of the psyche and social conventions. Madness, aberration, are not presented as escapes from reality, but rather as logical extensions of a latent pathology within society, of an existential fragility that intensifies in the face of power and manipulation. In this sense, The Servant is not just a psychological drama, but a profoundly incisive commentary on the transformation of British society in the 1960s, a period of uncertainty and upheaval of values, where old hierarchies began to crumble to make way for new and often more insidious forms of control.

A perverse and brilliant film that continues to reverberate with its disquieting topicality, inviting us to reflect on the fluidity of identities and the insidious nature of power in human relationships. A masterpiece that, while offering no easy answers, leaves an indelible mark on the spectator's soul, forcing them to confront their own dark side and the subtle dynamics of submission and domination that permeate every layer of civil life.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...