Close Encounters of the Third Kind

1977

Rate this movie

Average: 3.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

A film conceived, written, and directed by Spielberg, back when he still approached filmmaking in a, so to speak, artisanal way. Perhaps a purer period of his career, imbued with an almost obsessive meticulousness and an expressive freedom that anticipated but was not yet stifled by the titanic production machine of global blockbusters that would dominate the following decade. Close Encounters of the Third Kind emerges from this phase as a rare gem, a purest distillation of his nascent poetic vision.

And the results are nothing short of sublime, with the creation of a work in which mystery and hope dance intertwined, not as opposing elements, but as complementary forces that feed each other, giving rise to a captivating story that is simultaneously an inner odyssey and a cosmic epic. Here, mystery is not a mere narrative device to generate suspense, but rather a vehicle for the ineffable, for what transcends ordinary comprehension and pushes the individual beyond the confines of their daily perception. Hope, on the other hand, manifests as an almost mystical faith in the benevolence of the unknown, an antidote to the atavistic fear of the alien.

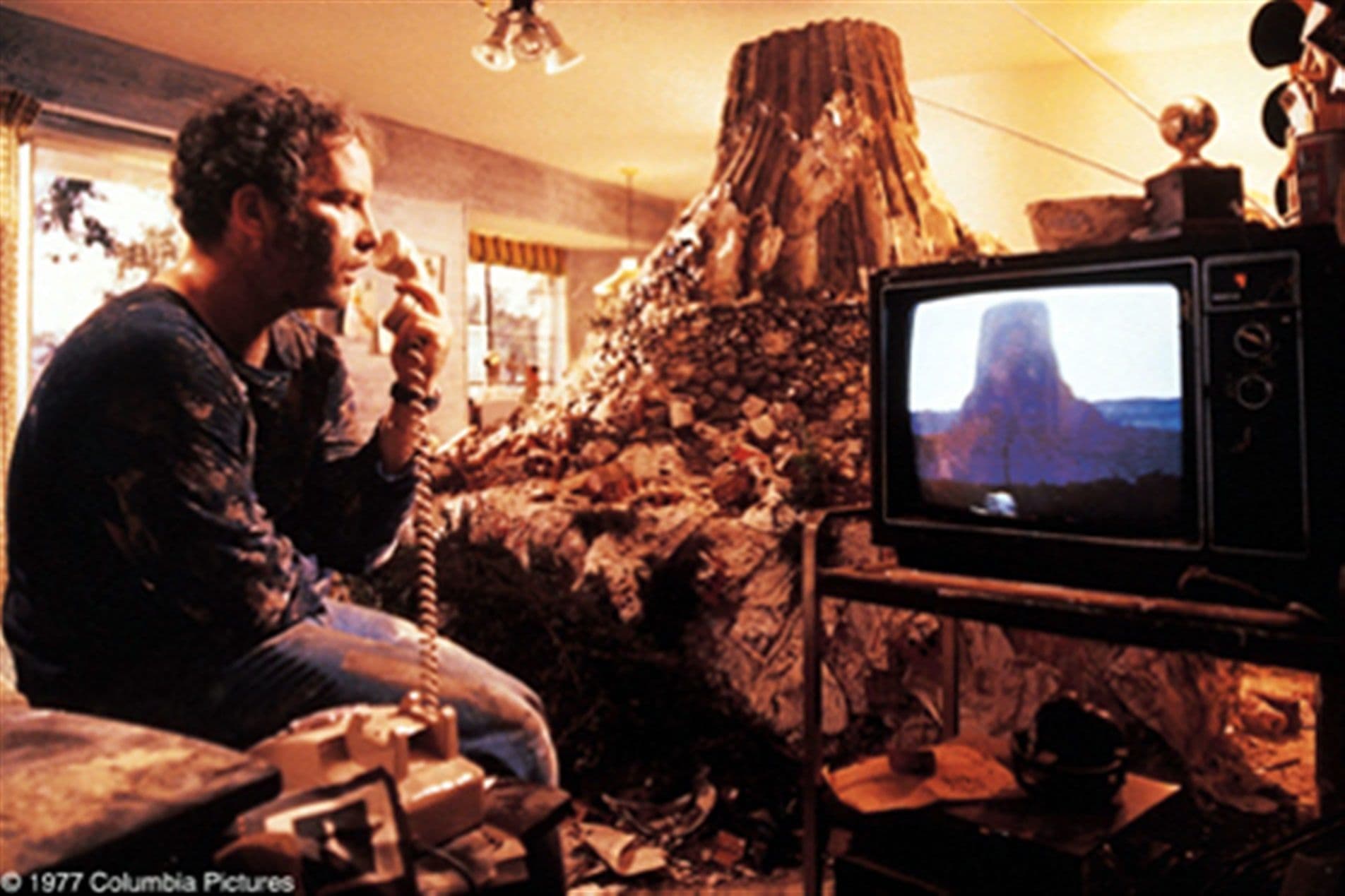

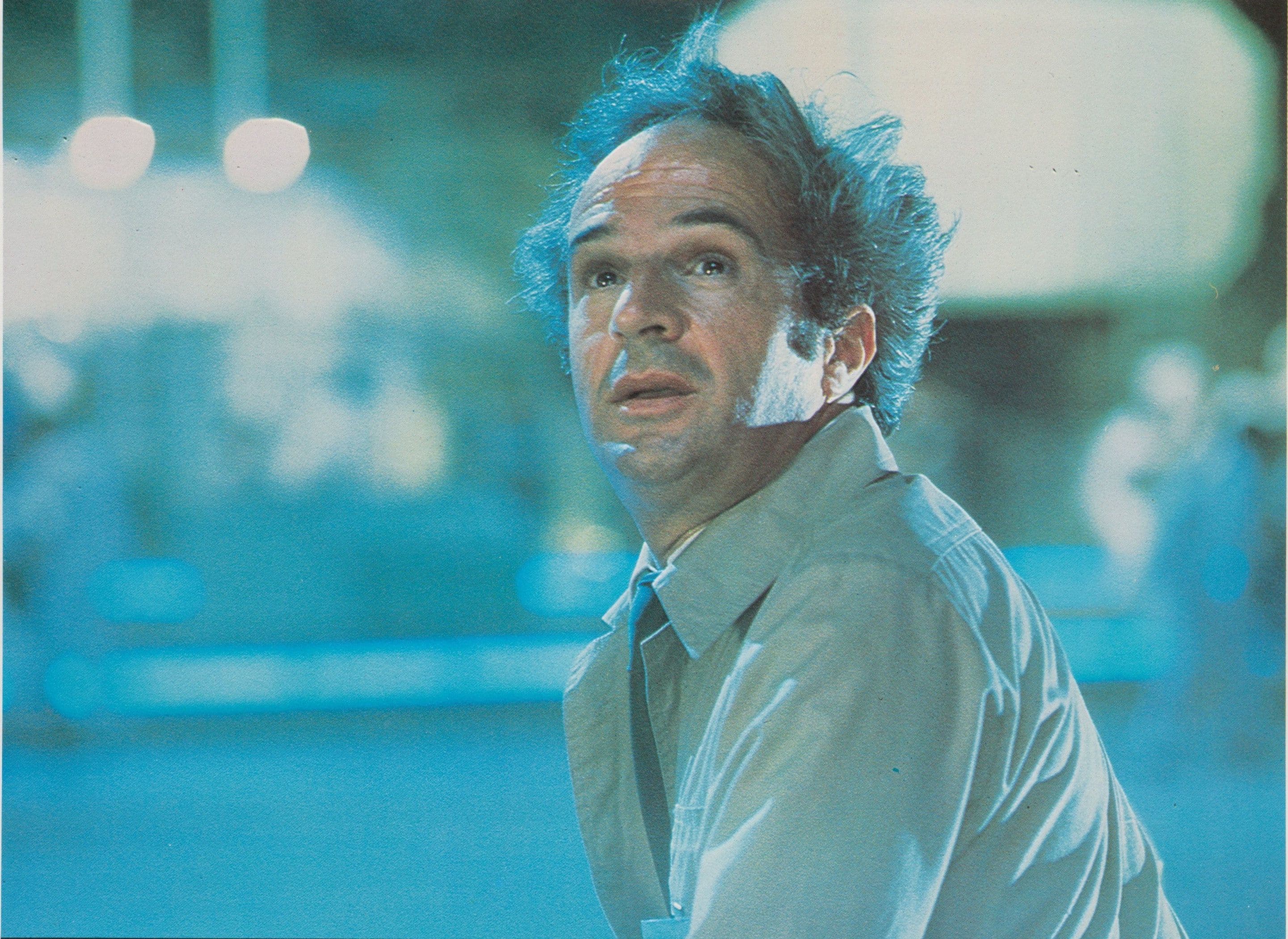

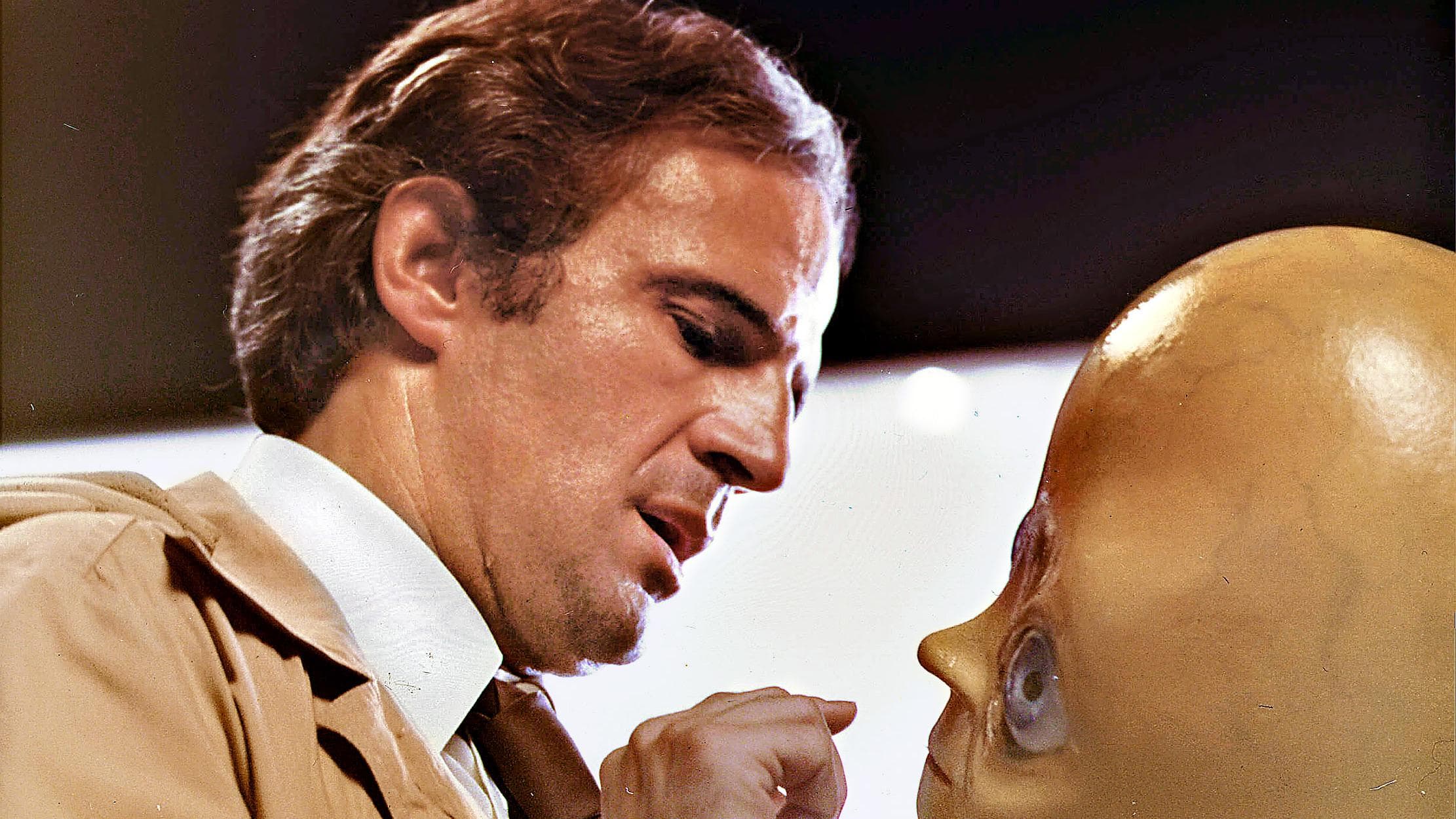

After witnessing the appearance of a UFO in the sky, a power-line worker, Roy Neary, portrayed with a feverish intensity by Richard Dreyfuss, begins to have strange visions. These are not random hallucinations, but a peculiar auditory perception: five distinct notes that continuously echo in his mind, an obsessive leitmotif that serves as a musical key to an enigma consuming him. The man cannot find peace, and, driven by an irrepressible impulse that transcends reason and pushes him toward apparent madness, decides to investigate the location suggested by his visions, a mountain image that powerfully imprints itself on his psyche, almost a divine footprint.

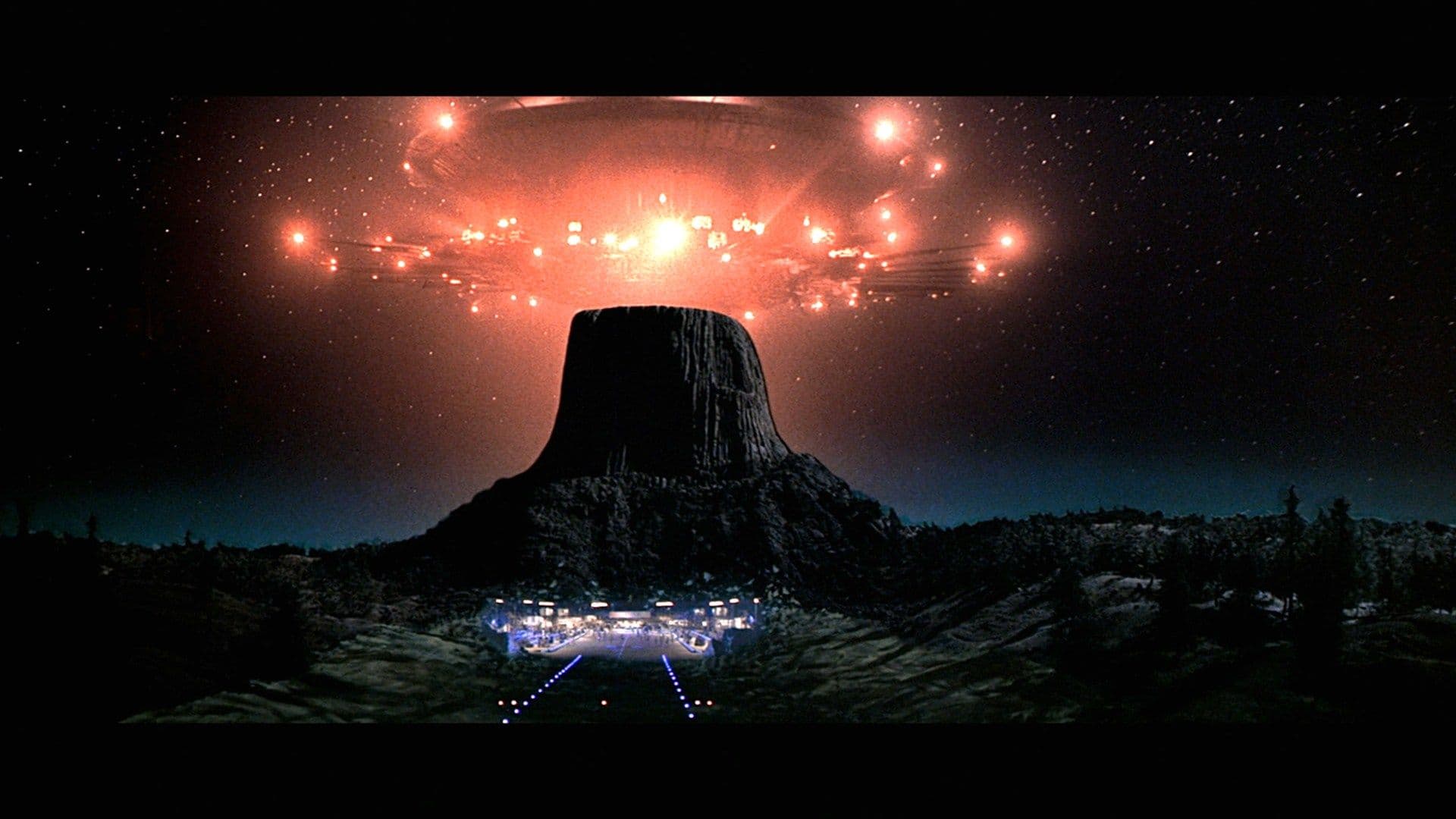

Toward the same location is also headed Jillian, a desperate mother who helplessly witnessed her son being pulled into a spacecraft, a trauma that indissolubly binds her to a common destiny and transforms her into an archetypal figure of maternal search and sorrow. At this location, which turns out to be Devil's Tower in Wyoming, the two discover a recently erected scientific center, hidden beneath a facade of fake biological threats. Inside the complex, scientists of many nationalities led by the Frenchman Lacombe, with the enigmatic and serene face of François Truffaut – a casting choice that, in addition to lending intellectual depth to the character, is a cinephile's homage to the master of the Nouvelle Vague – are studying the phenomenon of extraterrestrial contact.

It will be the beginning of an extraordinary adventure in which the word brotherhood will cross millions of miles in space to find in the "others" an interlocutor willing to communicate peacefully. This is one of Spielberg's greatest insights: to overturn the paradigm of alien invasion, typical of science fiction of the era, in favor of a first contact based on empathy, curiosity, and a universal language. The final sequence, with the musical dialogue between humans and extraterrestrials through the five notes, masterfully orchestrated by John Williams's score, is not only a triumph of special effects for its time (thanks to Douglas Trumbull's innovative work), but a moment of pure transcendence, a sonic and visual epiphany that celebrates the possibility of cosmic harmony. The lights and sounds are not a mere spectacle, but become the vocabulary of a new language, understood beyond earthly barriers.

Spielberg ventures into the purest form of science fiction, namely the pseudo-scientific realm of ufology, but with a seriousness and respect for the subject matter that elevate the genre to almost philosophical heights. The character of Lacombe is indeed modeled on the French ufologist Jacques Vallée, a scientist from the University of Texas who, among other things, was credited with compiling the first cartographic mapping of the planet Mars in 1962 on behalf of NASA. His theories, particularly those related to close encounters and the classification of sightings, were fundamental to the conceptual framework of the work, providing a substratum of credibility to an otherwise fantastical narrative. Although Vallée later radically changed his opinion on UFO sightings, essentially denying their veracity and asserting that any alien race could only originate from a dimension parallel to ours (a turn that adds a note of melancholic irony to the film's genesis), his initial influence was crucial.

The great aesthetic and conceptual value of this film remains unchanged. Spielberg certainly deserves credit for performing a kind of collatio among the various ufological theories of the time, successfully merging them into a narratively impeccable story that balances the wonder of the encounter with the anxieties of the search. Close Encounters of the Third Kind is not just a film about the possibility of extraterrestrial life, but a profound exploration of the human propensity towards the unknown, of our intrinsic thirst for knowledge, and of the hope of finding, beyond the boundaries of our small world, not a threat, but a reflection of ourselves, or perhaps a superior, more evolved version of our own consciousness. It is a work in which humanity takes a decisive step towards the light of knowledge that, in the blink of an eye, extends towards the most distant dimensions, a bridge cast over the cosmic abyss, a hymn to the adventure of the human spirit in the vast, mysterious, and promising universe.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...