Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion

1970

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

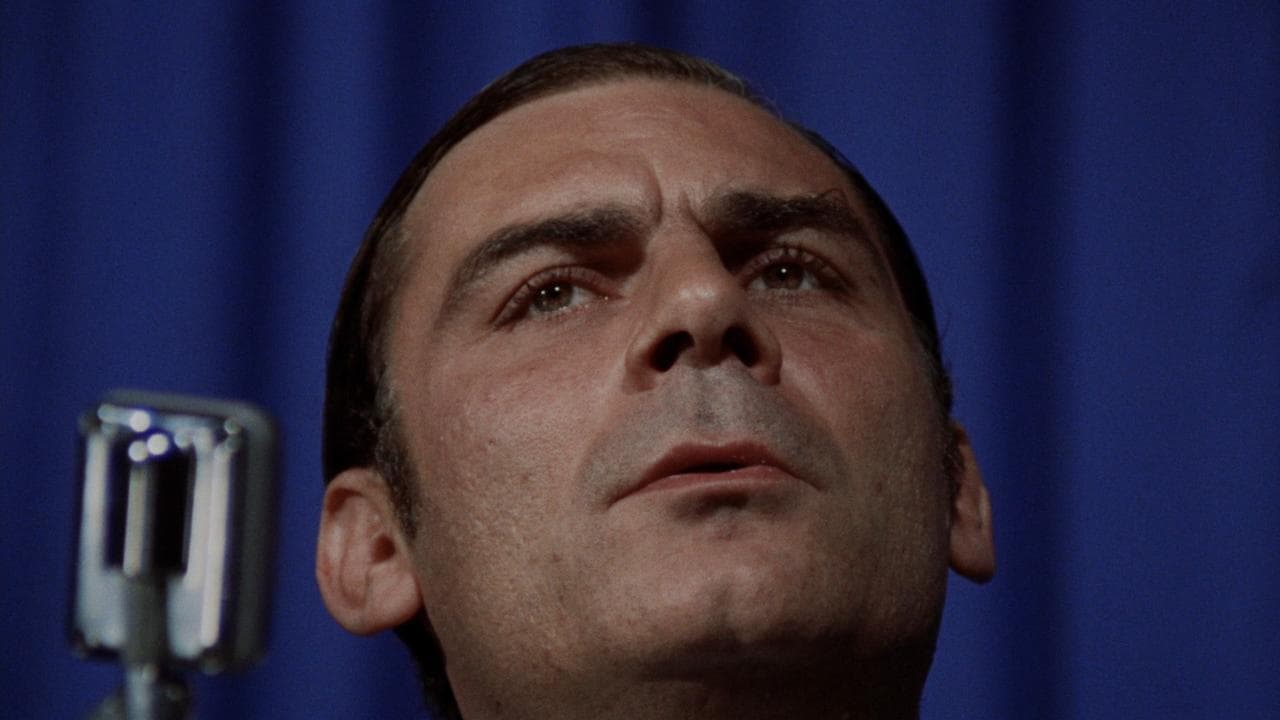

Director

Elio Petri pushes an immense Volontè to the limits of acting, embodying an ineffable character, the very face of unpunished and unpunishable power. Gian Maria Volontè, with his unparalleled intensity, does not merely interpret a role; he embodies it, lives it with an overbearing physicality and studied gestures that make him almost a grotesque puppet of his own hubris. His performance is a tour de force of neurosis, megalomania, and perversion, a vivid and disturbing portrait of a man who is simultaneously executioner and victim of the system he represents. This symbiosis between actor and character is one of the pillars underpinning the shattering power of Petri's film, which, not by chance, would win the Palme d'Or at Cannes and the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, establishing itself as a seminal work of Italian political cinema.

A powerful police commissioner murders his mistress and plants clues in the vain hope of being arrested, only to discover that his power is inherent in his terrible nature. This premise, which is in itself a logical and moral short-circuit, becomes in Petri's hands an almost psychoanalytic investigation into the craving for control and the impotence stemming from omnipotence. The spasmodic search for punishment is not so much a desire for redemption as a perverse verification of the limits of his own power: can the system incriminate one of its key pillars? The tragically obvious answer is a no that resonates like a sinister echo. His crime is not an act of ephemeral madness, but a scientific, almost laboratory-like, test of the inviolability of his status, a kind of Heisenberg experiment applied to morality and justice.

The comparison with certain figures of our time is emblematic, highlighting how this film manages to be absolutely modern in its analogy. Its contemporaneity is disarming. In an era where the public perception of institutional transparency is increasingly blurred, and where figures of power seem to operate beyond any accountability, Petri's "Doctor" does not appear anachronistic at all, but rather a prescient incarnation of an endemic evil. The film is not just a snapshot of state repression in Italy during the Years of Lead – a period of strong social and political tensions, where the boundary between "common crimes" and "political crimes" was artfully manipulated by the established power – but a universal and timeless critique of the intrinsic corruption and self-preserving tendency of every power apparatus. Petri's direction is as sharp as a scalpel, and, together with Luigi Kuveiller's claustrophobic cinematography and Ennio Morricone's unsettling soundtrack – an obsessive and sardonic leitmotif that underlines the madness and theatricality of the events – it creates an atmosphere of paranoia and alienation that transcends the pure investigative thriller to culminate in psychological drama and the bitterest social satire.

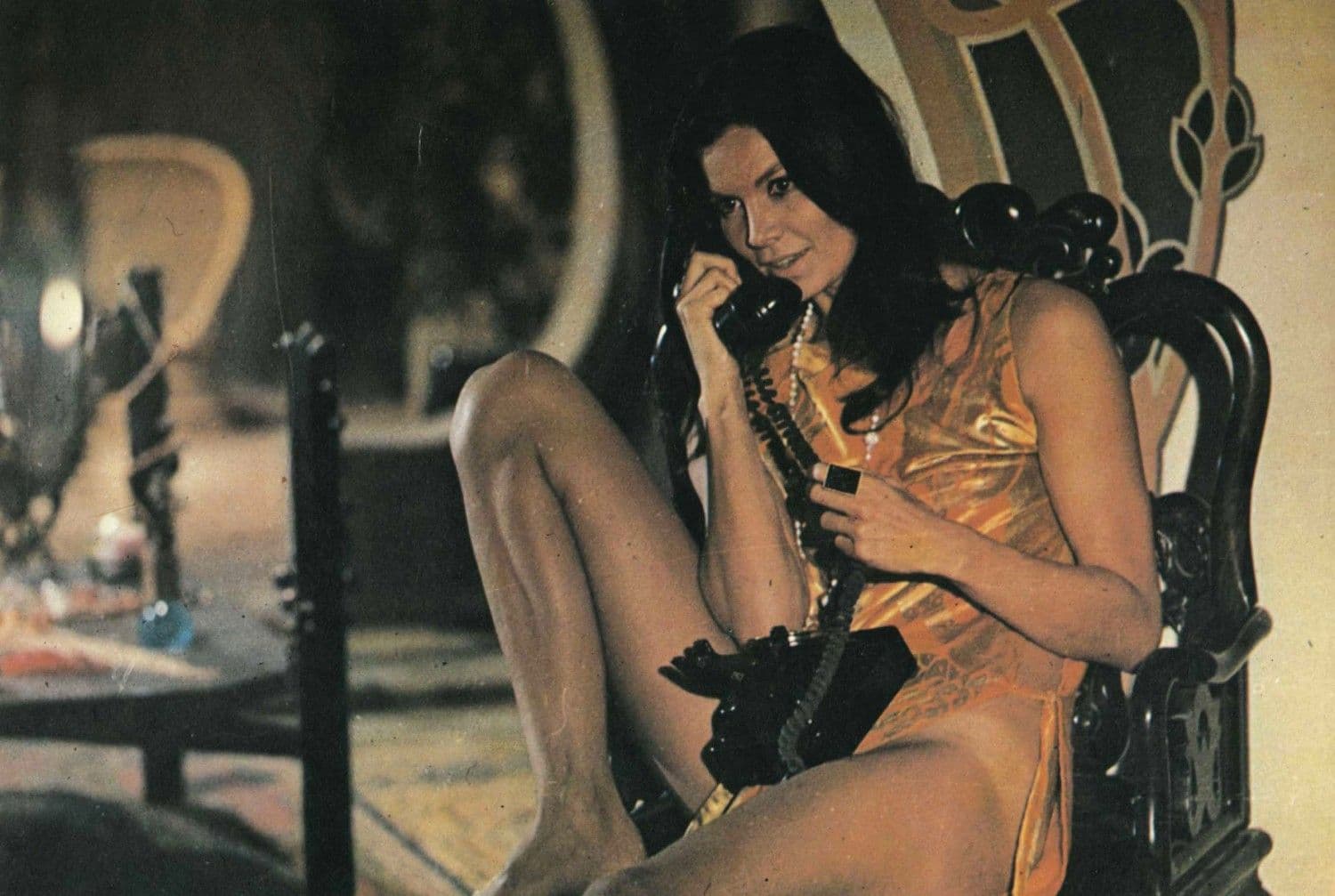

The central character of the film, a kind of deus ex machina who occupies the foreground like a demigod, exhibits remarkable complexity and offers various interpretations: from subliminal crime to the corruption of power, from sexual depravity to the obsessive and repressed pathology that he vents through his actions. The relationship with his mistress Augusta (a magnetic Florinda Bolkan) is not a simple adulterous liaison, but a battlefield where the sadomasochistic dynamic of control and submission plays out. Sex is dysfunctional, steeped in psychological and physical violence, a reflection of the Doctor's darkest impulses, which he attempts to purge (or rather to exhibit) through his "perfect" crime. His deviance is not a mere private vice, but becomes a metaphor for the deviance of an entire system which, like him, needs to manifest its strength through abuse and overpowering. Petri does not merely condemn the individual, but unveils the pathologies of an entire state body.

It is paradigmatic that the main character has no name but remains concealed behind a generic title, "The Doctor," almost to underscore his inviolability and immense power that cannot be scratched even by mere biographical detail. This anonymity is not a stylistic flourish, but a powerful narrative choice that universalizes his figure. "The Doctor" is not just anyone; he is the official, the archetype of authority, the impersonal face of a self-preserving State. The absence of a name depersonalizes him, rendering him not a man but the function itself, an essential cog in a bureaucratic and repressive machine. In this, the film echoes Kafkaesque atmospheres, where the individual clashes with a blind and sprawling bureaucracy, but with the difference that here the protagonist is himself the agent of that oppression, the system incarnate.

The Doctor, in his inaugural speech at the police headquarters for the "political crimes" section, proclaims to the audience: "From today I assume command of the political office. You all know that until yesterday I dealt with murders, and with a certain success. It is not without significance that they have assigned me, at this moment, to the directorship of the Political Office. This has been decided because the distinctions between common crimes and political crimes are increasingly blurring, tending even to disappear. Bear this in mind well: beneath every criminal, a subversive may hide; beneath every subversive, a criminal may hide." This wonderful monologue encapsulates in essence all the themes of this work related to the exercise of power: unchallenged power, decision-making power, inviolability of power, total subservience of those who do not hold power. This speech, almost Brechtian in its brutality and open declaration of intent, is the pulsating heart of the film, a true ideological manifesto of the protagonist and the regime he represents. It is a declaration of war on dissent, a justification for repression and totalitarian surveillance. The lucidity with which the Doctor articulates the fusion between common crime and political subversion is chilling, as it reveals the distorted logic of a State that sees every deviation from the norm as a threat to its own stability. The film's ending, with that disturbing Kafka quote and the Doctor who, in his bedroom, is surrounded by all those who should judge him but who instead tacitly absolve him, seals the inescapability of his condition and the impossibility of escaping the suffocating embrace of power, a power that does not need to punish its most loyal agents, as they are its very essence.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...