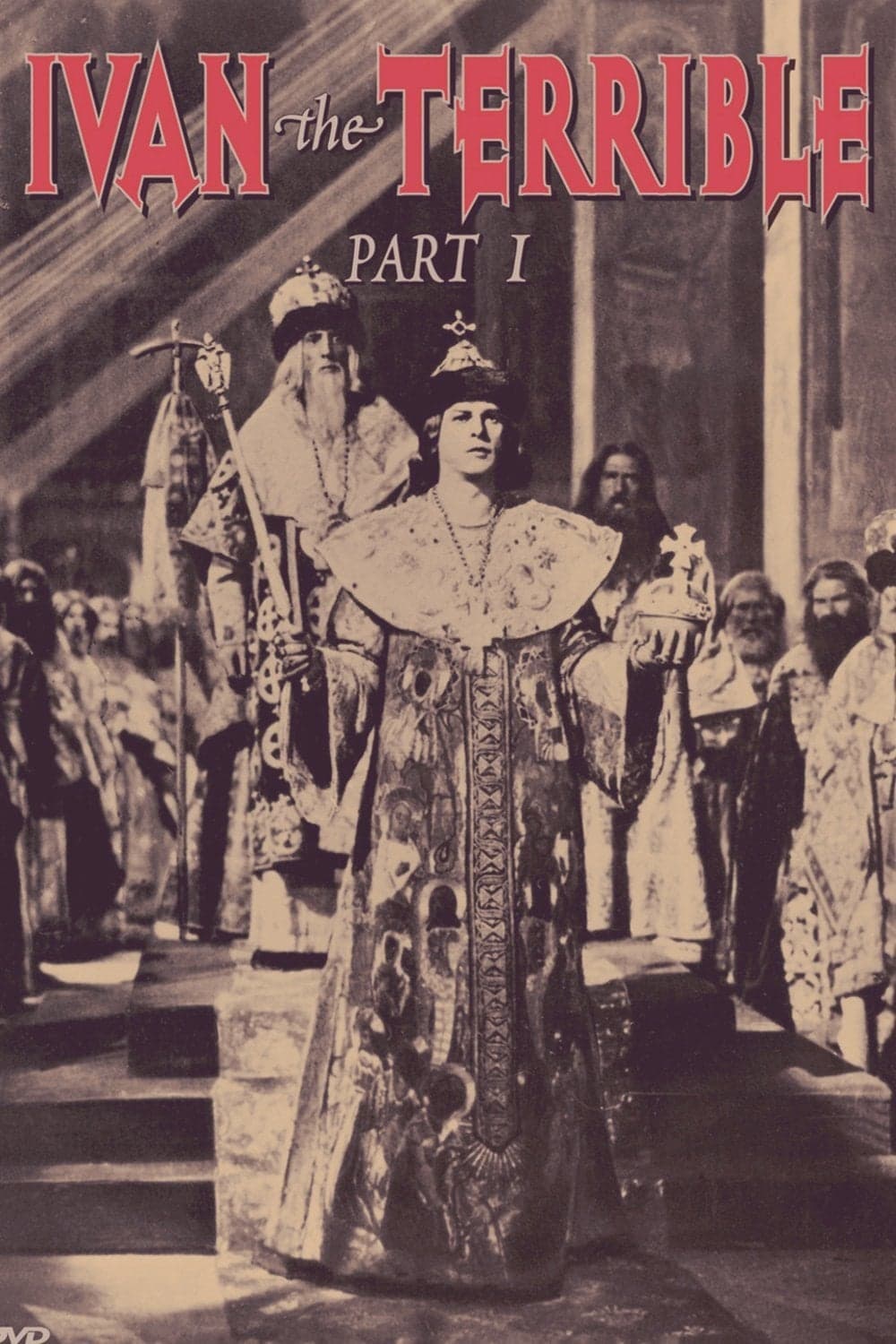

Ivan the Terrible, Part I

1944

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Ivan Groznyy is only the first part of a hypothetical trilogy that Eisenstein planned to celebrate the glories of a Tsar who was the first to unite the entire Russian galaxy. A pharaonic project, born under the aegis of Stalin himself, who saw in Ivan the Terrible not only a national hero, but also a precursor, a historical figure mirroring his own, projecting onto the 16th-century sovereign the determination and ruthlessness necessary to forge a unified empire against internal and external enemies. This commission, far from being a mere historical re-enactment, was a political and cultural operation of immense scope, intended to shape the Soviet collective imagination around the figure of the strong and visionary leader.

The second part, titled “The Boyars' Plot,” was completed and even screened in restricted circles in 1946, but never distributed to the general public during the director's lifetime, due to the censorship imposed on the work by the then-CPSU. Stalin, seeing in it a dangerous criticism of his own paranoia and tyrannical methods, did not forgive Eisenstein for depicting a Tsar isolated and tormented, prey to a delirium that led him to indiscriminate purges, perceiving the parallelism as a direct allusion to his own conduct. The official criticism, conveyed by chief ideologist Andrei Zhdanov, was merciless: the film was accused of "anti-historicism" and of having painted Ivan as "a weak-willed person, a sort of Hamlet." This condemnation deeply affected Eisenstein, already weakened by health problems, and compromised his ability to complete the magnum opus of his life. Its posthumous distribution in 1958, years after the Master's death, was a reparative act, albeit belated.

The third part was unfortunately never filmed; only two fragments were recently found in the archives of some obscure Moscow office. Its absence weighs like a shadow on the completeness of the ambitious fresco, leaving us only to imagine the culmination of what could have been the grandest and most complex cinematic epic ever conceived, a journey into the psyche of absolute power that would probably have further explored the darker and more tragic aspects of Ivan's reign.

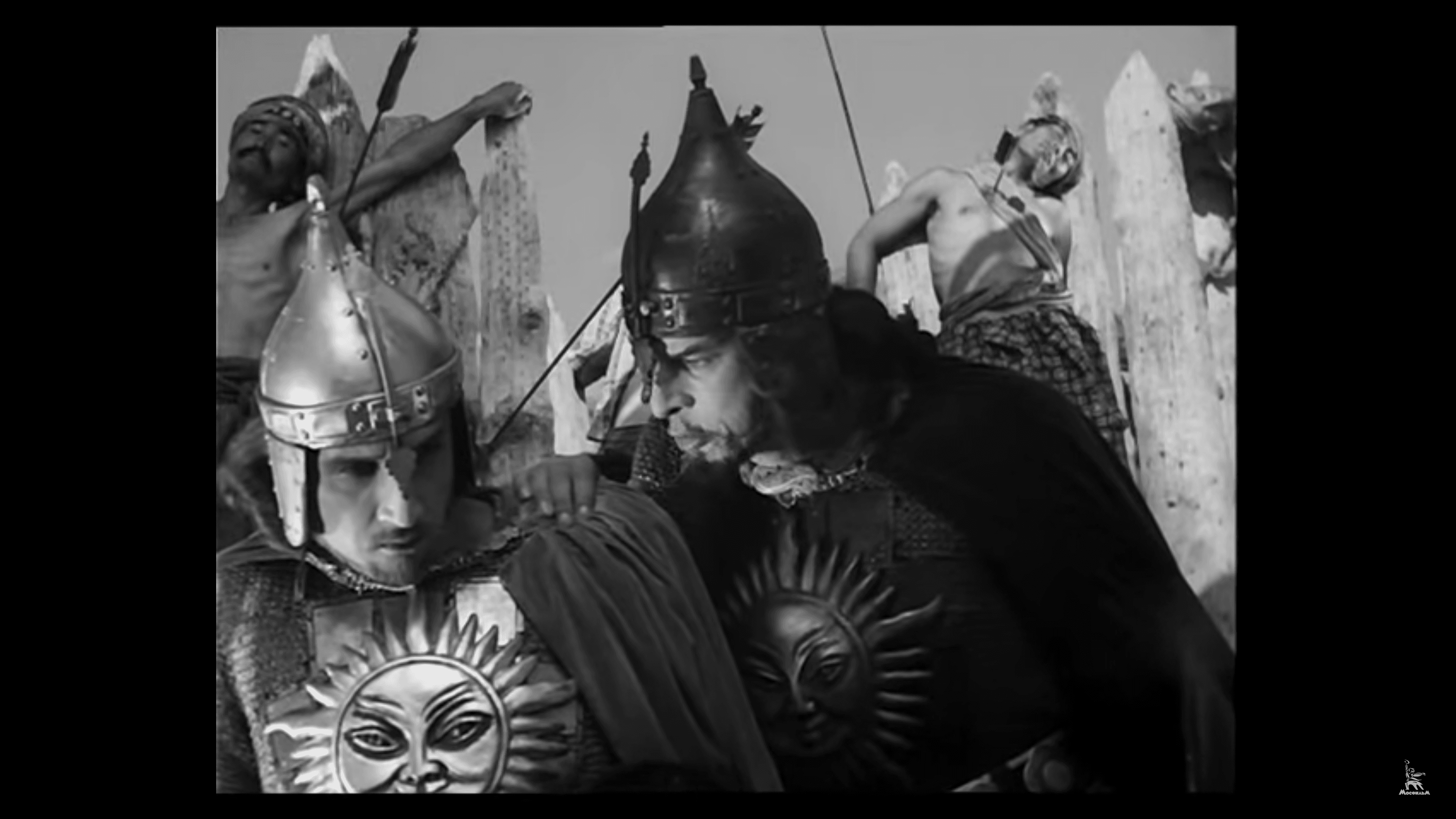

The film narrates the life of Tsar Ivan (1547 – 1584): the tumultuous court life, the conspiracy of hostile boyars who threatened central authority, his voluntary exile to a monastery – a politically astute move to force the people to recall him and thus legitimize his authority – his triumphant return to Moscow, and the conquering and pacifying wars. It is not a slavish biography, but a dense, almost operatic interpretation of half a century of Russian history, a crucial period in which the Grand Duchy of Moscow, through the charismatic and terrible figure of Ivan, became aware of a unity within reach, laying the foundations for what would become a vast empire.

The Master dwells on Ivan's dignity, pride, and semi-divine character, emphasizing the solitude of power and the gravity of the destiny that looms over one called upon to unify a dispersed and fragmented nation. This representation is the result of unprecedented stylistic layering. Eisenstein, master of editing and visual composition, goes further here. His camera sculpts bodies into living architectures, transforming the characters into almost Byzantine icons, with a use of chiaroscuro that evokes Caravaggesque painting or, closer to cinema, the atmospheres of great German Expressionism. Every shot is a painting, a monumental fresco where perspective depth is not merely a technical choice, but an expression of the sovereign's sidereal solitude and the monumentality of his historical task. Nikolai Cherkasov, in the role of Ivan, does not merely act; he embodies the character with a performance of magnificent theatricality, his deep eyes revealing an abyss of ambition, cunning, and, progressively, madness.

In doing so, he creates a masterful work in which perspective depth, aesthetic sensibility, and a flair for psychological inquiry reach peaks of elevated lyricism. The innovative use of extreme angles, the imposing set design that transforms the court and cathedral into environments of conspiracy and epiphany, and the sumptuous and stylized costumes contribute to forging a unique visual universe. But what elevates Ivan the Terrible beyond mere visual magnificence is the symbiotic integration with music. The soundtrack, composed by the brilliant Sergei Prokofiev, is not merely an accompaniment, but rather a narrative and emotional counterpoint, a character in itself that amplifies the drama, underscores the psychological leitmotifs, and imbues the entire film with an operatic dimension. The orchestral and choral scores merge with the images, creating a totalizing sensory experience that is simultaneously historical drama, Shakespearean tragedy, and grand opera. This synesthetic fusion, where sound and image are inextricably linked, is a lesson in cinema that still resonates with unheard-of power today.

Still unsurpassed by most contemporary directors, Ivan the Terrible remains a monument not only to the expressive power of cinema, but also to the complexity of the relationship between art and power. It is the swan song of a brilliant artist who, despite seeking to serve a regime, could not help but imbue his creation with his own unmistakable worldview, a vision that, ironically, ended up condemning him.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...