Jaws

1975

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Based on a novel by Peter Benchley, who also wrote the screenplay, a film that devoured every box office record at the time, allowing Steven Spielberg to enter the Hollywood Star System and establish himself as a young, thoroughbred director on whom to bet one's chips. An authentic cultural earthquake that not only reshaped the face of the film industry, effectively ushering in the era of the "summer blockbuster" with all its corollary of massive marketing and wide releases, but also carved an indelible mark on the collective imagination, redesigning the perception of seaside holidays and, more profoundly, the collective psychosis in the face of a primordial and invisible danger.

A gigantic shark threatens tourists in a holiday resort, Amity Island, an idyllic coastal town that thrives on summer tourist flows, whose mayor, for ignoble economic interest, underestimates the threat with tragic consequences. The local police chief, reluctant hero Martin Brody, a landlubber afflicted by thalassophobia, enlists the help of a marine biologist, the brilliant and pragmatic Matt Hooper, and a shark hunter, the gruff and charismatic Quint, a Homeric figure whose wisdom springs from a life spent among the waves and a past marked by tragedy. Thus begins an epic battle between the handful of audacious individuals and the Leviathan in the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean, a true sea odyssey that transforms into an existential confrontation between man and wild nature, between progress and the instinct for survival.

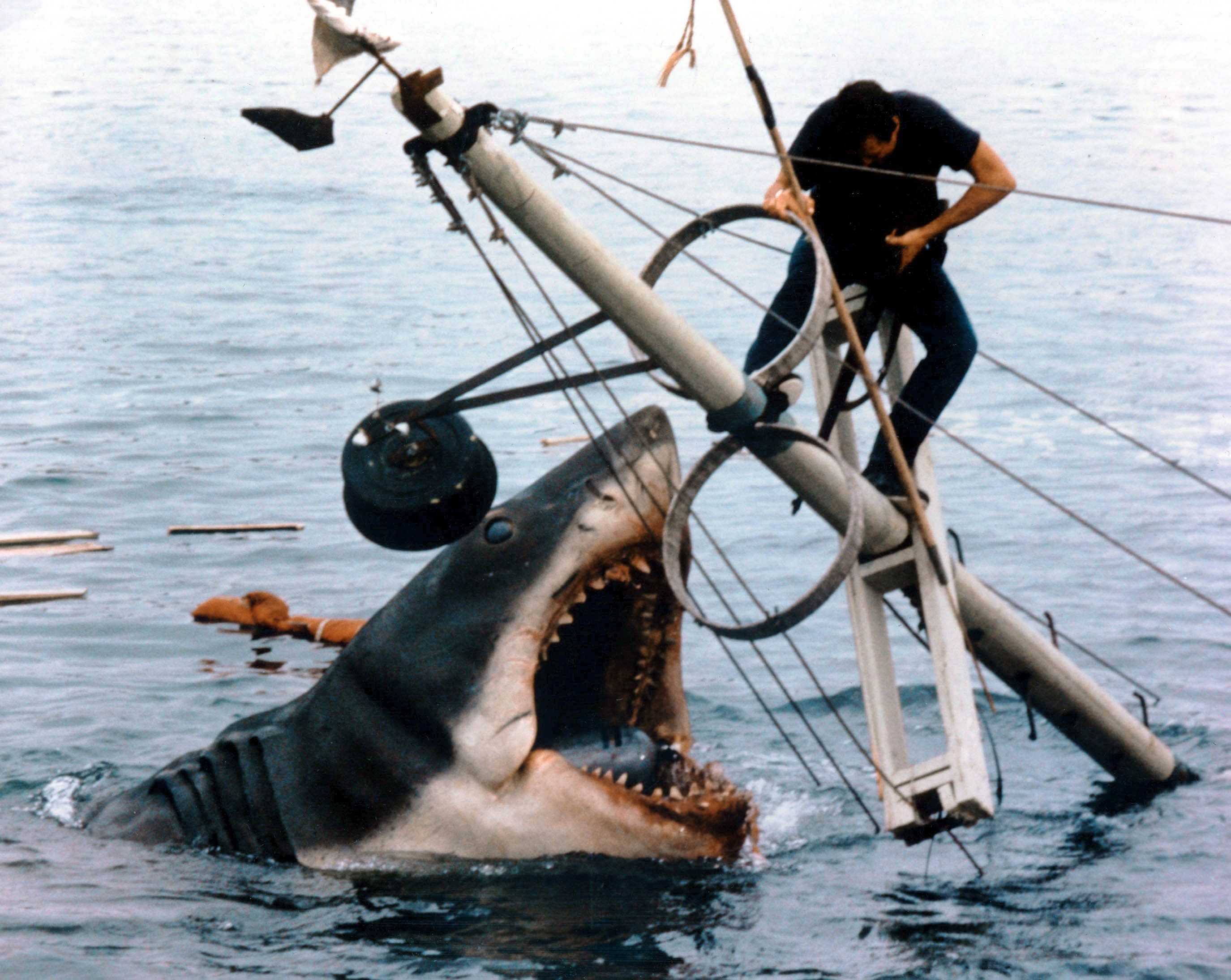

Behind the scenes of this nautical adventure, legend has it that much of the film's genius was born out of necessity. Bob Mattey, who was entrusted with the special effects, indeed built three mechanical sharks for the filming, affectionately nicknamed "Bruce" after Spielberg's lawyer: one to be used for underwater and surface-level shots, one for shooting it from the boat on the right side, and one for the left side. The latter two had hollow bodies to house the hydraulic mechanisms that moved the head, while the first had them inside its body and was effectively like a huge robot. It goes without saying that these solutions became standard practice and many others adopted Mattey's techniques. However, the almost constant malfunction of these animatronics in the salty waters of the Atlantic forced Spielberg to make a radical choice: to show the shark less and rely more on suggestion, the underwater point of view, disturbing details, and, above all, the soundtrack. This "unfortunate fortune" proved to be the key to success, because it was precisely the absence, the threat sensed but not yet seen, that generated an atavistic and penetrating terror that no special effect of the era could have matched.

Spielberg, for his part, weaves the web of sequences with seasoned craftsmanship (despite his young age), demonstrating a mastery of cinematic grammar worthy of past masters. Building, also thanks to Verna Fields' great editing work – the film's authentic "mother," who with her tight pacing and mastery in carving out tension gave the film its unmistakable imprint – a story that eliminates dead time and proceeds at a relentless pace. Spielberg's ability to manipulate narrative rhythm, alternating moments of apparent calm with explosions of pure horror, is masterful. Suspense is generated not only by the shark's attacks, but by its latency, its impending presence, brilliantly underscored by John Williams' celebrated musical score. The two ascending cello notes, capable of evoking the beast's proximity without ever showing it, have become a sonic archetype of impending danger, a true additional character in the film, as iconic as the shark itself.

The director's skill in creating the high-seas action scenes, where the shark's attacks assume an impressive visual impact, is remarkable, thanks both to the sparing and thus more effective use of Mattey's mechanical sharks and to the skilled hand that guides the camera. Bill Butler's camera moves with fluidity and precision, immersing us in the characters' anxiety, often with underwater point-of-view shots that reproduce the predator's perspective, or with tracking shots that amplify the ocean's vastness and indifference. "Jaws" is not only a breathtaking thriller, but also a keen investigation into human nature in the face of fear: institutional denial, unexpected heroism, the wisdom of the few who dare to challenge the unknown. A work that, almost half a century after its release, continues to define the genre, to terrify entire generations, and to demonstrate how true cinematic mastery lies in the art of suggestion, in the skillful building of tension, and in the ability to touch deep chords of the collective unconscious.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...