In the Heat of the Night

1967

Rate this movie

Average: 3.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Jewison's film was released in late 1967, a few months before Martin Luther King was brutally assassinated. This very concomitance is key to understanding the film: the latent and overt racism of the Southern USA was still very persistent in this, shall we say, civilized period. A bitter irony, considering that the nation had recently enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, attempting to dismantle the legal foundations of segregation. "In the Heat of the Night" does not merely denounce the legacy of a bygone era, but illuminates the still-deep fracture between legislation and social reality, between the facade of progress and the persistence of an atavistic hatred that slithered through the dusty streets of provincial towns, ready to explode like the racial tensions that would soon ignite American cities.

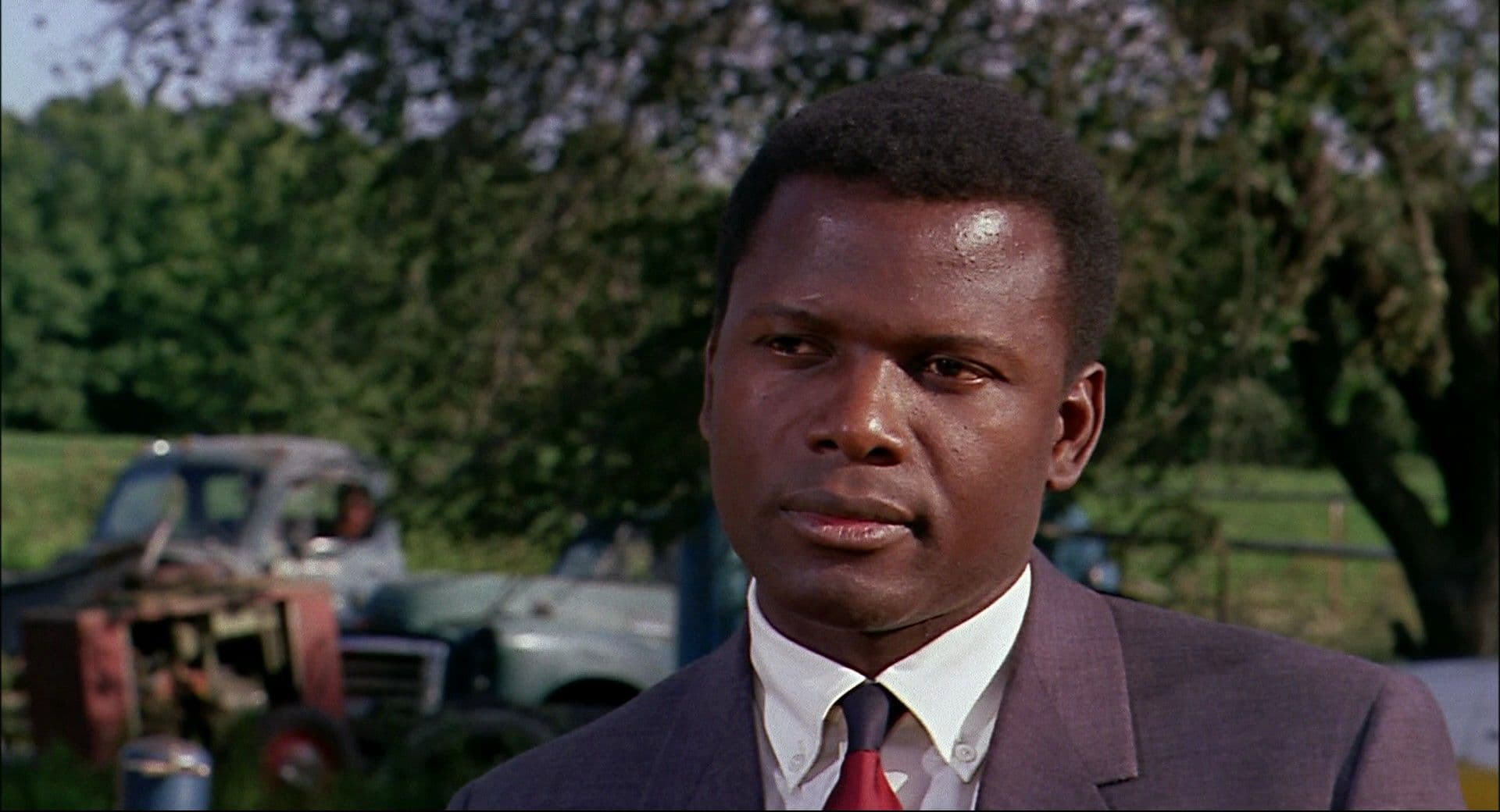

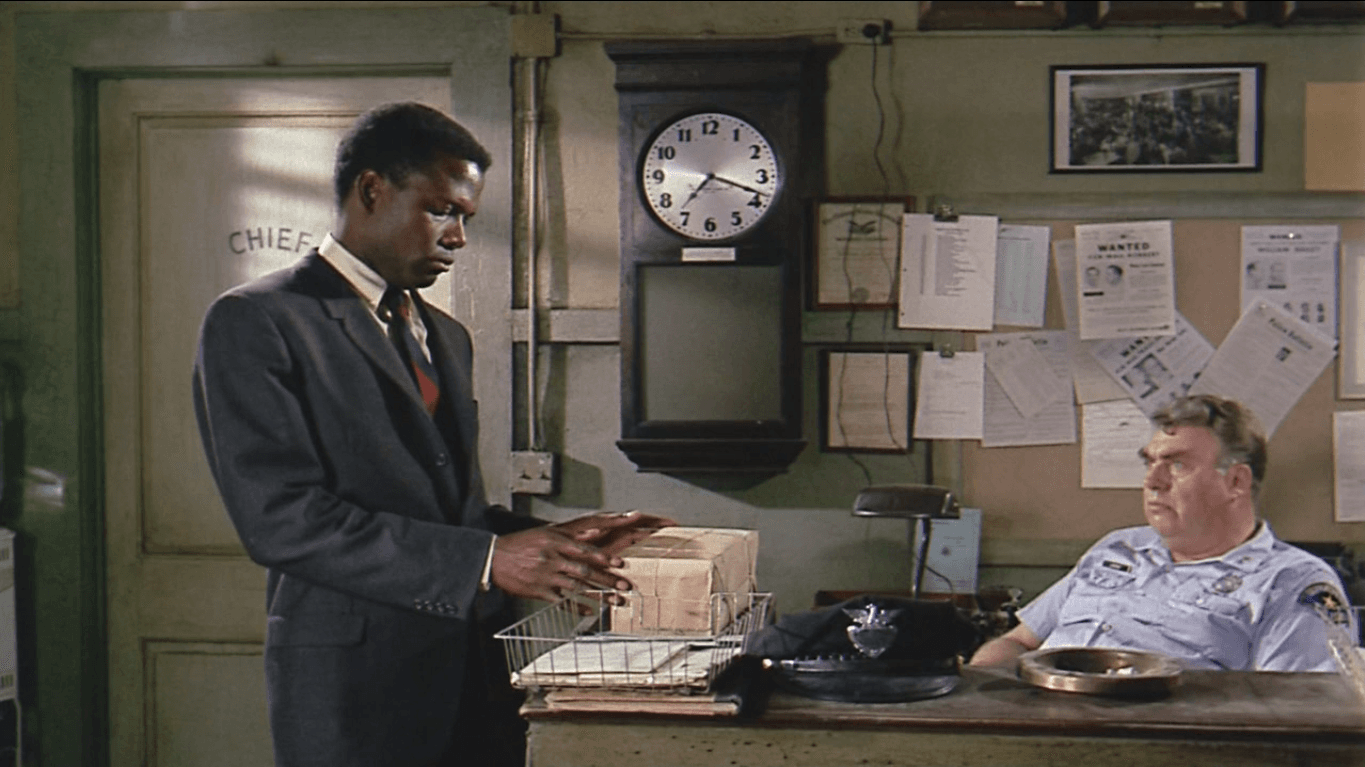

In this crucible of hypocrisy and silent violence, a rough and prejudiced local sheriff, Bill Gillespie (masterfully portrayed by Rod Steiger), is joined – against all his expectations and inclinations – by a Black Department of Justice inspector, Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier at the peak of his hieratic cinematic dignity), to solve an intricate murder case in a small Mississippi town. He is the archetype of the outsider who disrupts a stagnant order, but here the outsider is not just a new face; he is a living symbol of everything the racist community of Sparta detests and fears.

Racism and prejudice surrounding Tibbs's figure will significantly hinder his work. Every glance is a judgment, every word a veiled threat, every bureaucratic obstacle a manifestation of institutional hatred. His mere presence is a frontal challenge to the established order, an electric shock in a social fabric that feeds on segregation and a sense of white supremacy as obtuse as it is deeply rooted. From petty daily indignities to the explicit attempt to frame him for the murder, Tibbs is constantly under siege, forced to navigate a sea of palpable hostility that Jewison renders with an almost unbearable tension, accentuated by Haskell Wexler's claustrophobic and sweaty cinematography and Quincy Jones's bluesy and nervous soundtrack.

But his humanity, combined with his impeccable professional ability and forensic intelligence that astonishes his obtuse antagonists, will gradually win over the rough sheriff. The point of no return, the spark that ignites a fragile understanding, is the famous slap scene: when Tibbs, outraged and provoked by a wealthy white landowner who mocks him, returns a resounding slap with lightning dignity, the entire power dynamic is overturned. It is not just an act of self-defense, but a resounding self-affirmation, a categorical refusal to accept the subordination imposed by the color of his skin. At that moment, Gillespie, though shocked by Tibbs's audacity, begins to perceive not only the man's integrity but also his moral strength, understanding that prejudice is a luxury his own profession – the search for truth – can no longer afford. From that moment, an unexpected and deeply recalcitrant alliance begins to take shape, based on a grudging respect rather than an easy friendship, outlining a "buddy movie" ante litteram, but with a rarely equaled sociopolitical complexity.

"In the Heat of the Night" thus stands as a vibrant work of social denunciation, against all forms of racism and vulgar prejudice, but it is also a keen examination of the nature of power, authority, and justice in a divided America. Jewison, with his measured but incisive direction, does not merely show us Evil, but explores its roots, painting a South pervaded by an almost Southern Gothic atmosphere, where secrets and social pathologies are hidden beneath a veneer of normalcy.

A great performance by Rod Steiger, which earned him an Oscar, renders a credible Gillespie in his transformation, a provincial lawman who, while never fully abandoning his gruffness and internalized preconceptions, is forced to confront a reality that transcends him, learning to esteem a man whom society dictates he should despise. Beside him, Sidney Poitier delivers one of his most iconic performances, shaping a character of rare elegance and restrained anger. His Tibbs is a beacon of competence and professionalism, a man who, despite having to swallow bitter pills of humiliation, never loses control, channeling his indignation into an impeccable investigative logic, almost as if to demonstrate, with every deduction, that his professional and human worth transcends the color of his skin. The contrast between Steiger's visceral intensity and Poitier's controlled dignity creates an unforgettable cinematic dynamic, central to the film's success.

Memorable scene: Tibbs's examination of the murder victim's body under the incredulous gazes of the medical examiner. Tibbs professionally analyzes the corpse with care, requesting chemical compounds and tools from an astounded local mortician, who turns out to be more of an amateur embalmer. It is the triumph of science over superstition, of modernity over backwardness, of competence over ignorant prejudice. It is not just a demonstration of investigative skill, but a symbolic subversion of power, with the Black man assuming intellectual control over a traditionally white domain, imposing his superior knowledge and analytical ability.

A work that almost seems to use the criminal aspect of the story as a pretext to dwell on prejudice and racial discrimination and its squalid legacy in everyday life. The crime is the MacGuffin, the catalyst for a much deeper confrontation between two visions of America, two ways of being, two worlds that clash and, in part, understand each other. While other films from the same year starring Poitier (like "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner?") explored racial themes through the more "comfortable" prism of bourgeois interracial relationships, "In the Heat of the Night" immersed itself unfiltered into the visceral violence and hatred of the South, offering a rawer and more authentic picture of the tensions tearing the country apart. A film that, not coincidentally, was shot in Illinois and Indiana rather than Mississippi, precisely because of segregationist laws that would have prevented the integrated cast and crew from operating freely. Despite the sequel ("They Call Me Mister Tibbs!") and a television series, none have managed to replicate the power and subtlety of the original film, whose ethical and social resonance remains intact, a perennial warning about the fragility of progress and the tenacity of prejudice.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...