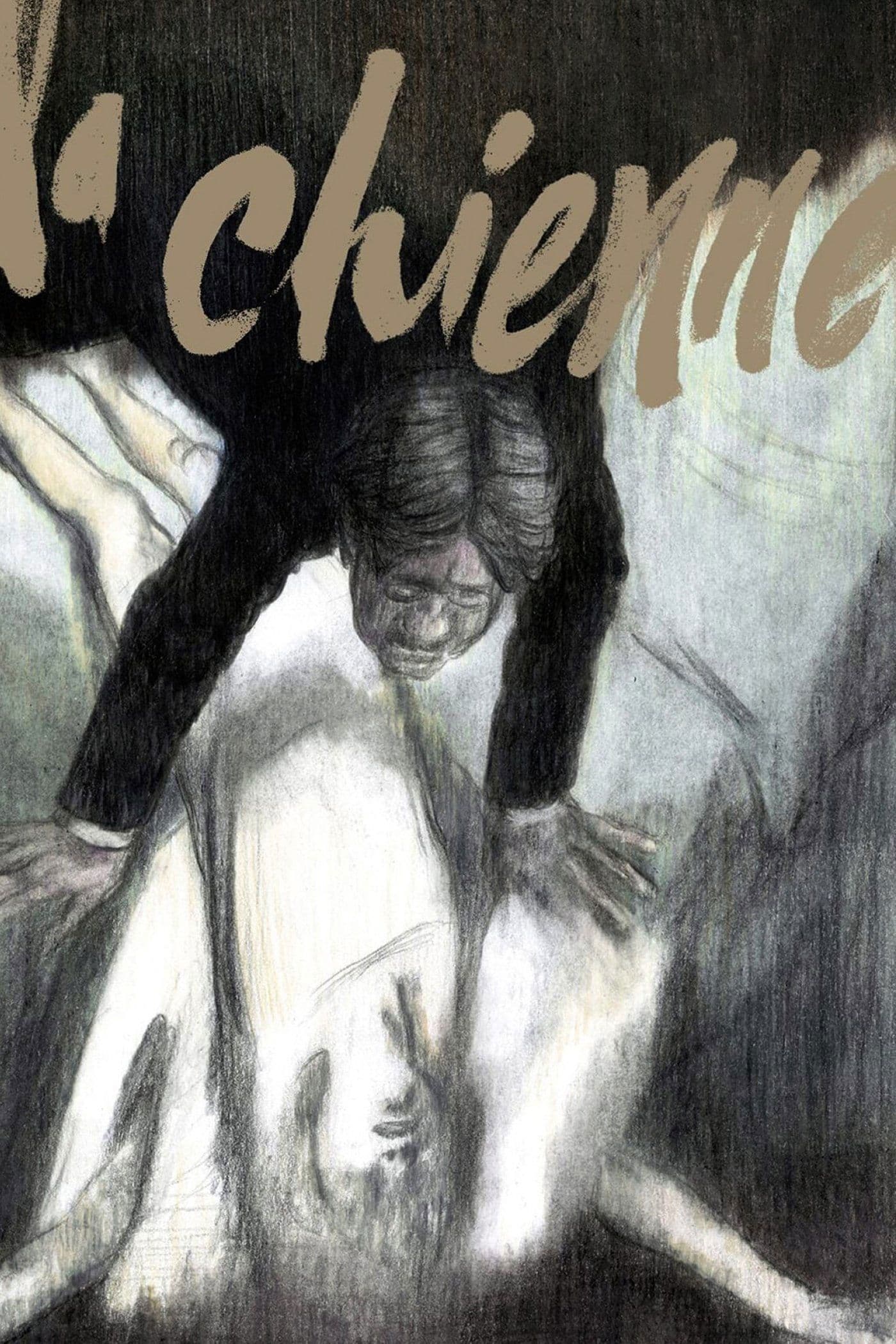

La Chienne

1931

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Renoir's first sound film. The great French Master demonstrates perfect command of the new medium, creating a sensational fresco in which each character is depicted within a tailor-made dimension. This early mastery in the use of sound, often in stark contrast to the still rigidly theatrical approach of many of his contemporaries, is not limited to the mere reproduction of dialogue, but extends to understanding sound as an atmospheric and psychological element intrinsic to the narrative. The psychological investigation is functional to the narration and does not clash with the aesthetic result; on the contrary, it corroborates it. The film, based on the eponymous novel by Georges de La Fouchardière, is a raw and realistic fresco of French society of the time, populated by marginalized characters, victims of their own passions and the hypocrisies of a bourgeois world that proves to be not only hypocritical but profoundly decaying. This is not a static representation, but a vivid and pulsating portrait of France between the two wars, a nation still deeply scarred by the conflict, grappling with a changing moral landscape and the erosion of traditional certainties. Renoir, with his keen and compassionate yet never sentimental gaze, leads us into the folds of the human soul, showing us with disarming clarity the contradictions and fragilities of his characters, almost in a surgical dissection of souls.

The plot focuses on Maurice Legrand, a timid bank cashier, stifled by an unhappy marriage to an authoritarian and petty wife. He is the embodiment of a mediocre and repressed bourgeoisie, a man who, though not a tragic hero in the classical sense, becomes the sacrificial victim of an ineluctable destiny and a society that offers no escape from his silent despair. His grey and monotonous life is disrupted by an encounter with Lulu, a young prostitute, with whom he falls madly in love. For her, Legrand is willing to do anything: he supports her, buys her jewelry, and even steals to satisfy her whims. But Lulu, cynical and opportunistic, betrays him with a young and violent boxer, Dédé. In this context, Lulu emerges as an archetypal femme fatale, but stripped of any romantic glamour; she is a pragmatic predator, herself a product of a ruthless environment where love is a commodity and survival the only law. The love triangle with Dédé, the primitive and brutal boxer, intensifies the drama, revealing Legrand's pathetic frailties and his inability to confront such a raw reality. Jealousy and despair drive Legrand to commit murder, after which he seeks refuge in a life of vagrancy and degradation. His transformation from diligent employee to uxoricidal killer out of passion and then to tramp is not a mere sequence of events, but a radical inner metamorphosis, a loss of every vestige of dignity that Renoir captures with disarming clarity, almost Flaubertian in his ruthless observation of the common man. Renoir, with a dry and essential narrative style, shows us Legrand's progressive descent into hell, his loss of identity, his alienation from society.

Legrand, in his path of degradation, moves further and further away from society's moral values. His descent is not just a criminal act, but a progressive desensitization, an immersion into an existential abyss that makes him, in retrospect, almost a precursor to Camusian or Sartrean characters, an anti-hero embodying the absurdity of the human condition in the face of universal indifference. His crime isolates him morally, making him an outcast, a man with no more ties to the world. His solitude thus also becomes a moral solitude, a condition of isolation and alienation from shared values. Legrand's solitude is closely linked to his alienation from modern society. His repetitive and mechanical work, his oppressive family life, his inability to find a place in the world, all contribute to creating a sense of deep unease and isolation. This alienation is not merely personal, but reflects a broader crisis of modernity, where the individual is crushed between social constraints and inner emptiness. The figure of the final vagrant, almost a human wreck, becomes a powerful symbol of this definitive break. Legrand's search for a way out of solitude leads him to take refuge in a world of illusions. His love for Lulu, his life of revelry, his emancipation from his wife, are all illusions that prove ephemeral and lead him to an even deeper solitude. Renoir manages to portray this titanic sense of solitude with his masterful artistic technique. The shots often isolate him in space, emphasizing his detachment from other characters or confining him to corners suffocated by bourgeois furnishings or urban desolation. The use of sound, well beyond the mere reproduction of speech, becomes an essential narrative element: the deafening city noises that amplify Legrand's isolation, the eloquent silences that underscore the emptiness of his illusions, the occasional cacophony that reflects his mental disorientation. This technical mastery, which anticipates poetic realism and later Italian Neorealism (of which La Chienne was a significant source of inspiration for its focus on everyday drabness, marginality, and the use of non-professional actors in some scenes, albeit with a narrative structure still firmly classical), is also evident in the almost documentary-like representation of certain Parisian environments. At the time, the film was an object of scandal and censorship for its ambiguous morality and explicit depiction of prostitution and crime without moralizing rhetoric, a courage that distinguishes it from much contemporary production. A masterpiece of modern cinema that marks a clear boundary in Renoir's speculative aesthetic journey and opens new horizons for cinema of introspection and social commentary. A benchmark for Neorealism. It is a work that, despite being a brilliant example of 1930s cinema, powerfully dialogues with our present, questioning us about the nature of passion, freedom, and revenge, and leaving us with the unsettling awareness that Legrand's fall could be the fall of any of us, trapped between desire and disillusionment. Its legacy resonates in the cinema of Buñuel (consider a certain bourgeois disenchantment) and, in some respects, even in the melancholic atmospheres of Carné. A work that speaks through the complex psyche of its protagonist and, after mercilessly laying it bare, drags us into his mental vortex of perdition. And in an instant, we are lost with him.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...