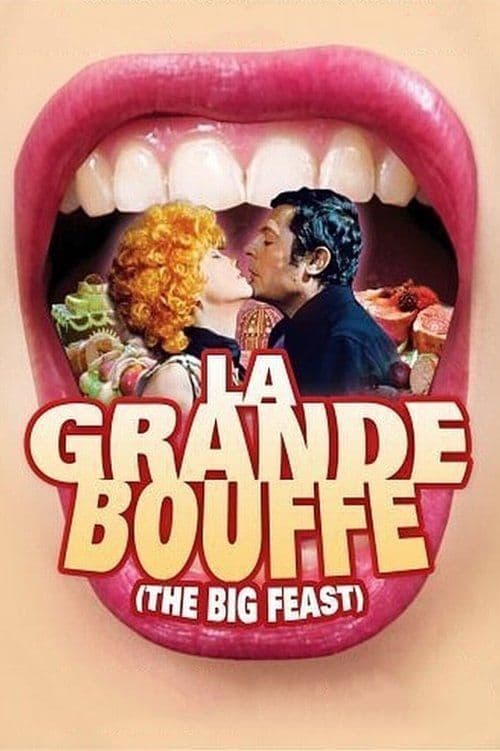

La Grande Bouffe

1973

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A film that in some ways strongly resembles Pinter's theatre: both for the theatrical nature of the screenplay (the setting is almost exclusively a single, claustrophobic set that becomes a metaphor for an existential prison from which there is neither escape nor possible redemption), and for the cynical, grotesque, and bitterly ironic tone that permeates the plot. The echo of Beckettian absurdity is not merely an aesthetic suggestion, but a stylistic hallmark that Ferreri masterfully wields, creating a suspended atmosphere, imbued with an indefinite threat, a palpable unease that stems not from an external event, but from the implosion of an inner world. The obsessive repetitiveness of gestures, the incommunicability underlying the ritual of the meal, even the progressive deterioration of reason and body, recall the plays of the English playwright, where waiting and the unspoken are often more eloquent than any dialogue, and stasis is a prelude to inevitable wasting away.

This work by Marco Ferreri is one of acute and penetrating intelligence, confirming him as a storyteller and filmmaker of great stature. A challenging author, resistant to easy categorisations, whose filmography is a gallery of extreme characters, often at odds with social conventions or trapped in surreal dynamics that reveal the emptiness of contemporary living. From Dillinger Is Dead (where murder and voyeurism transform into gestures of desperate, almost infantile, rebellion) to Bye Bye Monkey (a lucid and grotesque analysis of the crisis of male identity in consumer society), Ferreri has always explored the excesses of bourgeois society, the commodification of feelings and bodies, anticipating with foresight the pathologies of a post-industrial era now devoted to unlimited consumption and existential bulimia.

The story is that of four men who find themselves in a farmhouse with a common goal: to die of sex and food. But it is not a suicide understood as a desperate or final act. It is rather a methodical, almost scientific, self-annihilation, a last bulwark against an existence emptied of meaning. It is the extreme representation of a civilization that has reached the apex of its material prosperity, but which has at the same time spiritually consumed itself, finding in the wildest excess the only, perverse, remaining form of authenticity. Food, from essential nourishment, transforms into a tool of self-destruction, into a poison that slowly corrupts not only the body, but the last semblance of humanity, in a funereal banquet that celebrates the end of an era.

The four are a restaurateur (Ugo), an airline pilot (Marcello), a television producer (Michel), and a magistrate (Philippe). These are not random choices, but archetypes of a tired, opulent, and disillusioned Italian and European bourgeoisie in the 1970s, a decade of ferment and disillusionments. The restaurateur, master of food and conviviality, becomes his own sacrificial victim, his own executioner; the pilot, a symbol of freedom, escape, and technological control, shuts himself in a self-inflicted prison, shedding his wings; the television producer, architect of images, illusions, and mass entertainment, confronts the raw, ineluctable reality of flesh and its decomposition; the magistrate, guardian of law and civil order, celebrates its definitive anarchy and the collapse of all moral structure. It is a sort of decadent pantheon, an assemblage of figures who embodied the success and power of an era and now decree its failure in a Dionysian ritual of self-consumption, a last, desperate cry for liberation from emptiness.

A special mention for all four lead actors; it is truly difficult to say who prevails. Marcello Mastroianni, Ugo Tognazzi, Michel Piccoli, Philippe Noiret: giants of international cinema who, in an act of courage and total artistic abnegation, agree to shed their masks as seducers, intellectuals, or heroes, to embody a grotesque, almost repulsive, humanity in collapse. Their chemistry is palpable, a symphony of gestures, glances, and silences that communicates a deep melancholy and a resigned complicity in this mad undertaking. It is an ensemble performance that elevates the film from pure provocation to a profoundly human, almost philosophical, inquiry into the end of a historical and spiritual cycle, offering a physical and psychological performance that transcends all limits.

Ferreri is not interested in expressing moral judgments on the protagonists' behaviour, nor whether their undertaking might have social implications concealing a denunciation: Ferreri is interested in documenting the dreamlike side of this story by making it violently collide with the plane of reality and creating a sort of intermediate channel in which to funnel the narrative. This liminal space is the pulsating heart of the film, an unexplored territory where reality deforms into nightmare, and the dreamlike materializes with an almost unbearable crudeness. It is not a cinema of thesis or sententious judgment, but rather of acute, ruthless, and detached observation, which leaves the viewer the task of deciphering the meaning of such self-destruction. One might think of certain moments in Luis Buñuel's cinema, where the banquet and conviviality transform into surreal and disturbing rituals, revealing the most recondite urges and moral decadence behind the veneer of civilization. Ferreri, however, adds a carnal, visceral dimension that Buñuel often sublimates into intellectual allegory; here, food and bodies are inescapable, almost tangible presences, in their abundance and subsequent, unsettling corruption.

A grotesque film, surreal if you will, in its meticulous psychological characterization of the four Dionysian beings seated at the table, facing a story poised between drama and jollity with a touch of bitterness that tinges the entire narrative and explodes in the finale. The Dionysian, understood not only as a celebration of sensory excess, but as a regression to a primordial state, a rejection of Apollonian order in favour of chaos and dissolution. The initial boisterousness, made up of jokes, provocations, and ostentatious lightheartedness, progressively gives way to an existential weariness, an apathy that is a prelude to annihilation. The film, presented in competition at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973, caused scandal and heated debates, precisely for its ability to challenge conventions, break taboos, and lay bare, with unsparing lucidity, the obsessions of a society in transition, already irrevocably devoted to hyper-consumption. It is a work that had the power to prefigure, with almost prophetic lucidity, the rampant spread of a culture of excess and consumption which, decades later, shows no sign of abating, but has indeed amplified. La Grande Abbuffata remains a burning warning, a chilling allegory of a world that, in its indiscriminate gorging, risks suffocating in its own opulence, imploding upon itself in a final, macabre banquet.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...