L'Atalante

1934

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A foundational work in the history of cinema, conceived and shaped by a very young Jean Vigo, who shot it at just 29 years old and died soon after filming. His short and unfortunate existence, marked by the tuberculosis that would extinguish him prematurely, lends the film an almost mythical aura, that of a brilliant, short-lived genius whose creative flair was cut short too soon. It is no coincidence that the work is often counted among the "cursed films" or "damned films" due to its troubled production: Vigo, already weakened by illness, had to face the hostility of the Gaumont production, which mercilessly cut over twenty minutes from it, changed its title from "Le Chaland qui passe" (The Barge Passing By) to "L'Atalante" (in reference to a popular song of the time), and imposed an editing style that partially distorted its original poetic meaning. Only years later, thanks to the dedication of cinephiles and critics, the film was restored and re-released in its version closest to Vigo's intentions, fully revealing its greatness.

Despite being made with limited means and in a difficult context, the work managed to anticipate themes and stylistic elements that would be adopted by movements such as the Nouvelle Vague, profoundly influencing filmmakers of the caliber of François Truffaut and Alain Resnais. Vigo's formal freedom, his ability to blend everyday reality and dreamlike lyricism, represent a true epiphany for future French auteurs. The film anticipated many of the themes and stylistic elements that would later be dear to the movement's directors, such as attention to the everyday, stylistic experimentation, non-conformist characters, and existential themes. Vigo did not merely narrate a story but delved into the souls of his characters and the very essence of human experience, with a surprising modernity for its time.

The oneiric dimension in Jean Vigo's "L'Atalante" also holds fundamental importance, contributing to creating the film's hazy and surreal atmosphere and to sculpting the characters' psychology. Vigo, son of the anarchist Miguel Almereyda, seems to inherit from his father a vocation for deconstructing conventions, which here translates into the exploration of the subconscious, a territory then little explored by cinema. The dream plane becomes a means to delve into the characters' psyche and to reveal aspects of their personality that do not emerge in everyday reality. The sequence, for example, in which Juliette submerges herself in the water and glimpses Jean's face reflected on the surface, represents an attempt to restore Juliette's unconscious to the narrative—her hidden desires, her fears, and her fantasies—in an act of pure cinematic lyricism that blends the materiality of water with the fluidity of desire. It is a moment of rare beauty, a dive into the very essence of love and longing.

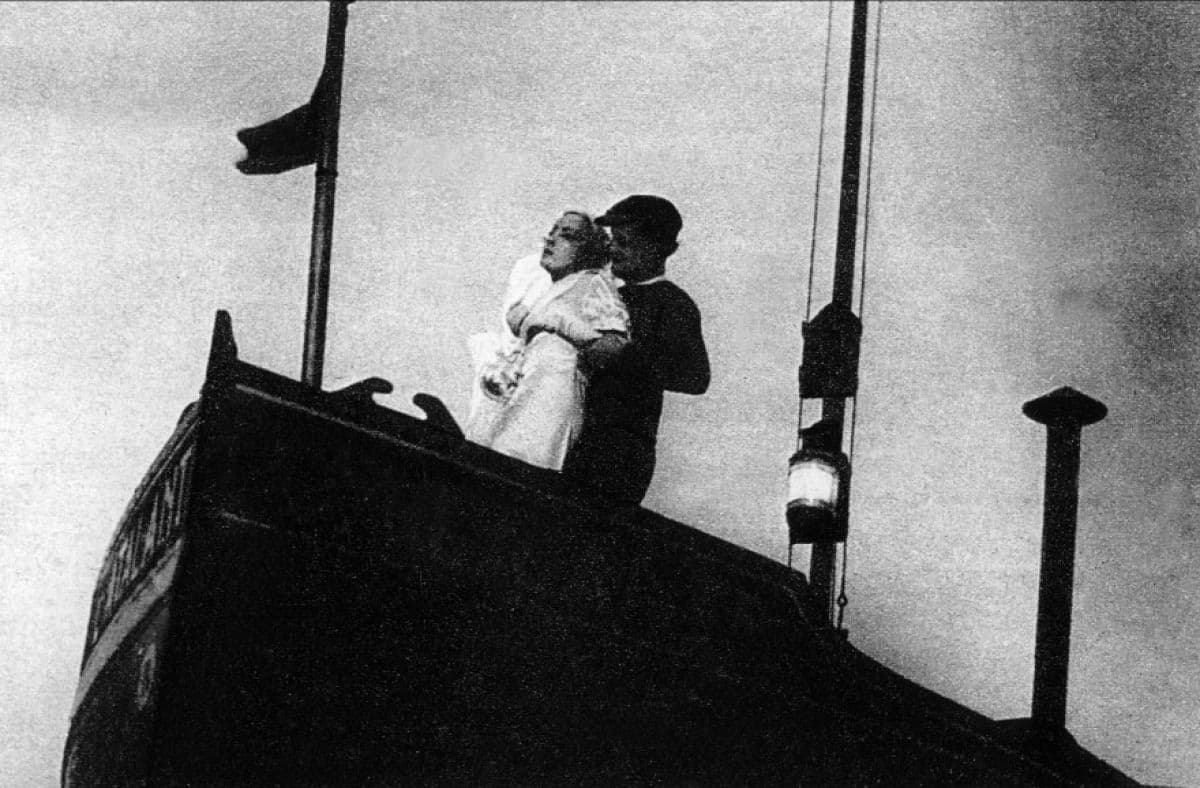

The story is that of Juliette, a refined and strong-willed woman, who falls in love with and marries a barge captain, Jean, and goes to live with him on the boat, the eponymous Atalante. The barge itself becomes a character, a floating microcosm that navigates between the familiar and the unknown, between the provinces and the big city. Aboard, living with them, are the gruff and wise Père Jules, a philosophical sailor and collector of eccentric objects from everywhere, and a young cabin boy, an almost angelic and innocent figure. Due to the monotony of life on board and the river routine, combined with Jean's jealousy and the allure of Parisian social life, the woman progressively detaches herself from the man until she returns to the capital's baroque life. Their separation, far from being definitive, becomes a test, a catalyst for the discovery of the profound bond that unites them. She would find the man years later and realize she had never truly separated from him, in a reaffirmation of a love that transcends physical presence.

A complex and fascinating work, also made famous in Italy by the opening credits sequence of Ghezzi and Giusti's Fuori Orario, where the underwater sequence in which Juliette dives is replayed—a true visual calling card for generations of cinephiles. The cinematography is splendid, veiled by a hint of surrealism and always with a kind of temporal suspension at the culmination of the shot. The director of photography Boris Kaufman, brother of the famous Dziga Vertov, with suggestive and poetic shots, contributes to creating an atmosphere dappled with lyricism, a poetic realism ante litteram that blends the texture of everyday life with the enchantment of dreams. The performances of Dita Parlo and Jean Dasté, intense and natural, bring to life two unforgettable characters, two lovers lost in a pantheistic love that devours everything, even Time, almost as if their union were a primordial force of nature itself. The love between Juliette and Jean is presented as a totalizing concept, one that pervades every aspect of their lives and of the film itself. Vigo shows us a passionate, visceral love that overwhelms the protagonists and pushes them to overcome every kind of barrier; even when they drift apart, their love strengthens and stretches through time and space, demonstrating its resilience and indissoluble nature.

Vigo, as mentioned, deeply inspired many directors with this film, which became a beacon for auteur cinema. His influence manifests not only in its themes but also in its approach to direction, in the rejection of narrative conventions, and in the search for an emotional truth beyond logic. In Resnais' "Hiroshima mon amour" (1959), the love between the two protagonists, as in L'Atalante, is linked to a journey—in this case, a journey into memory and trauma—where intimacy is revealed through flashbacks and interior monologues, a clear debt to Vigo's ability to explore the deep psyche. In Jean-Luc Godard's "Pierrot le fou" (1965), love is a journey, an escape from society and conventions, along the lines of the story between Jean and Juliette, but with the addition of the nihilism and disillusionment typical of its era. The restlessness of Godard's characters finds its root in the search for freedom of Vigo's protagonists. In Truffaut's "Jules et Jim" (1962), love is a force that unites and separates, creating deep bonds but also conflicts and tensions; here too, Vigo's lesson is discernible in Truffaut's narrative, in his ability to portray the complexity of human relationships with lightness and depth. And the list could continue ad libitum, perhaps even including the tendencies of Italian neorealism in its attention to the everyday, or even certain independent American cinema for its empathy towards marginal characters. The fundamental thing is to keep in mind how much this young and unfortunate director influenced and inspired the artistic genesis of so many filmmakers with just one work, and for this singular and brilliant contribution, it is a fact for which we should be immensely grateful.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...