The Lives of Others

2006

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Das Leben der Anderen is an attempt by a German director (born in Cologne and trained in New York) to convey the true meaning of a life lived under the aegis of the socialist regime in East Germany in the 1980s, shortly before the fall of the Wall. It is not an aseptic historiographical analysis, but rather an almost phenomenological immersion into the most intimate and harrowing implications of a society where individual freedom is an illusion and trust an inaccessible luxury. A Western perspective on how the GDR regime affected the freedoms of its citizens, certainly, but at the same time a universal exploration of human dignity tested by tyranny.

The result is an undoubtedly brilliant film, yet another testament to the good health of German cinema in recent times, a fertile period that has managed to confront its recent past with sensitivity and intelligence. From Good Bye, Lenin! with its bittersweet nostalgia to Downfall - The Last Days of Hitler, a dramatic epic on the abdication of an ideology, German cinema has rediscovered the power of historical narration, and The Lives of Others fits into this vein with a depth and stylistic sobriety that distinguish it. A work with sober tones, almost austere in its staging, centered on a story set in the GDR shortly before the fall of the Wall, written and directed by a young and promising director, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, whose debut immediately captured international attention, so much so that he was immediately co-opted by Hollywood after the success of this film, an invitation that, in retrospect, did not replicate the brilliance of this debut work.

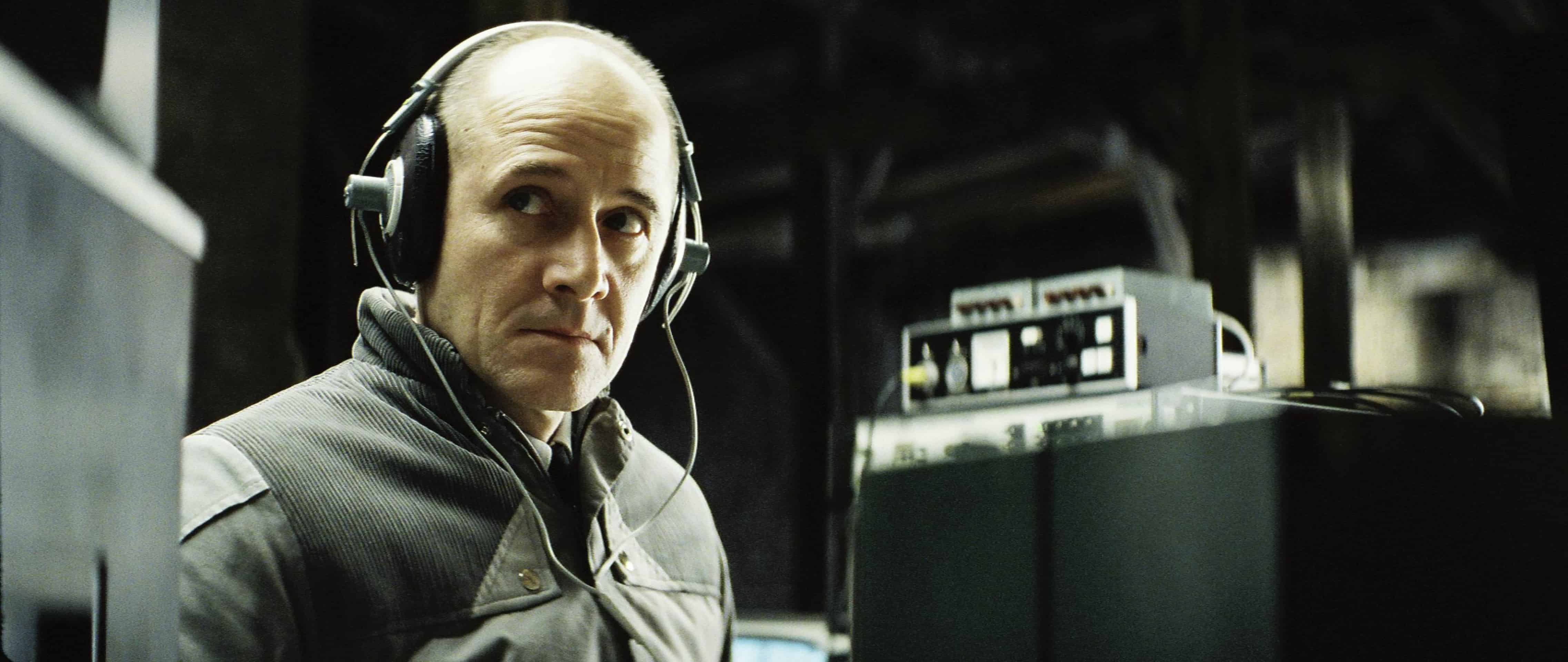

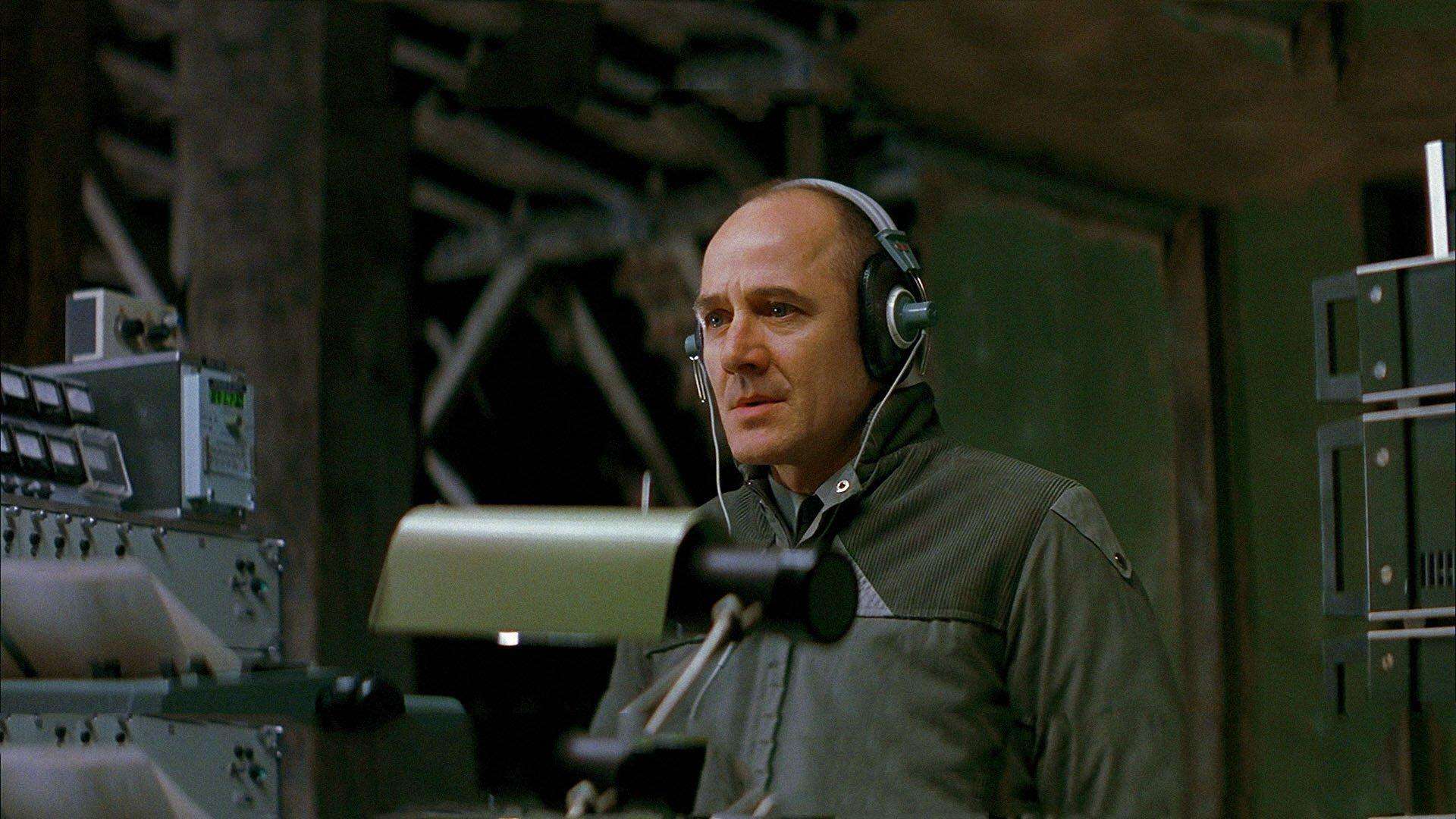

Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler is a man of unblemished integrity, a fervent supporter of the communist line and a loyal servant of the socialist State. His existence, devoid of personal affections and ambitions, is entirely devoted to the cause, embodying the archetype of the zealous bureaucrat, the impersonal face of the system. The officer is in charge of the wiretapping services when he receives the request to monitor Georg Dreyman, a successful playwright, and Christa-Maria Sieland, his partner and celebrated actress, an assignment that actually conceals the sordid personal motivations of a high-ranking party official.

Entering the couple's life as a spy, Wiesler does not merely record voices and conversations; he immerses himself, almost against his will, in their intimacy, their joys and sorrows. It is in this forced voyeurism that he will discover how his dogmas, built on years of indoctrination and blind obedience, are nothing more than an ephemeral house of cards. Progressively, his rigid soul begins to melt, unable to resist embracing the fervent ideals of the playwright, a man truly in love with his homeland and suffering to see it crushed by the oppressive yoke of the communist dictatorship. The turning point, both emotional and intellectual, is perhaps the listening to the “Sonata for a Good Man,” a piece of classical music that Dreyman plays on the piano: a sonic epiphany that shakes the foundations of his alienated existence, revealing to him the cathartic power of art and the profound beauty of human empathy, qualities that the regime sought to eradicate. At the same time, Wiesler will realize that the espionage operation is nothing more than a squalid means used by his superior, Minister Bruno Hempf, to eliminate the playwright from the scene and thus reach his wife, with whom the minister is in love, revealing the moral corruption and cynicism that lurk at the highest echelons of power.

The work possesses a dual significance: it is a hermeneutic inquiry into the overheard word, a voyeurism, so to speak, dialectical, where the act of perceiving another's conversation becomes a tool for self-recognition and ethical questioning. And at the same time, it is a disdainful critical analysis of a military apparatus that used widespread espionage and the annihilation of consciences as an Orwellian deterrent to subjugate the masses. The film depicts a society where every whisper can be a betrayal, every thought a crime, echoing the chilling paranoia described by George Orwell in 1984, but with a subtler, almost Beckettian nuance, delving into oppressive silence and forced isolation.

The speculative aspect of the work is perhaps the most fascinating: when Wiesler is holed up in the basement, facing the house he is spying on, and remains for hours listening, immobile and silent, he appears as the archetype of the Man in the Shadows, the invisible ear that perceives every sound. His solitude, so radical, makes him an Observer par excellence, a filter through which the viewer himself is invited to contemplate the lives of others, and by extension, their own. Essentially, it is the materialization of the paranoia that affects each of us when we have the impression that someone, or something, is listening to our words; a paranoia elevated to a system of totalitarian control.

There are many cinematic references. The most immediate is to Coppola's The Conversation, where this theme of overheard words similarly frames a cynical and bitter analysis of shared logos, on the latent paranoia of every sentient being to have their most intimate secrets stolen. But Donnersmarck's echoes extend further, touching on the strings of existential drama à la Haneke, especially in his surgical approach to the violation of intimacy, albeit with diametrically opposed outcomes in terms of hope. There is also a reference to the capacity of art to become a vehicle for salvation, a recurring theme in post-Wall cinema, consider Polanski's The Pianist, where music becomes a refuge and resilience against barbarism. In The Lives of Others, music, poetry, and theater are not mere background, but a driving force that impacts reality, capable of breaking the armor of a man and a regime.

The film, with its taut narration and controlled visual structure, manages to make oppression palpable without resorting to melodramas or easy sensationalism. It is a work that, while rooted in a specific historical context, raises universal questions about individual responsibility, the possibility of redemption, and the transformative power of knowledge and empathy. Wiesler's silent courage, his betrayal of the system for a greater good, is not just a narrative choice, but a powerful warning about human dignity that resists even in the darkest crevices. And in the moving final scene, when Dreyman discovers the identity of his guardian angel, memory becomes an act of justice, and a book, titled "Sonata for a Good Man," stands as a monument to lives that, though trampled, managed to leave an indelible mark.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...