The Tenant

1976

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

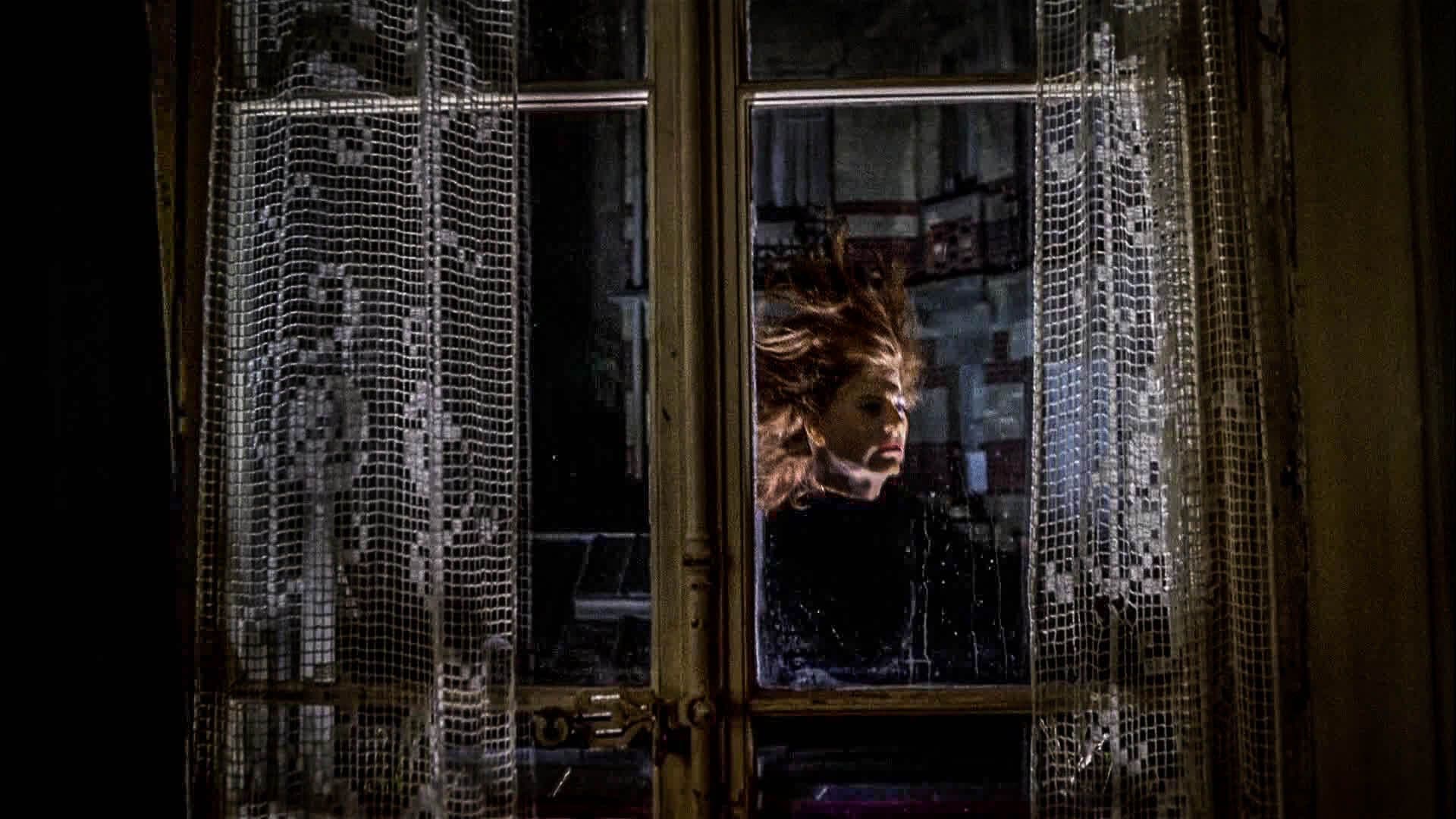

A nightmare shrunken within four cramped walls that become a vehicle for lysergic hallucinations and a thin boundary separating from whispered horror. Not an explosive or overtly supernatural horror, but rather a slow, insidious corrosion that drills through the foundations of perceived reality, leaving the individual at the mercy of their own disembodied psyche.

Polanski continues to tread the path of "domestic terror" from Rosemary’s Baby and Repulsion with this splendid The Tenant, which stands as the culmination of what critics have rightly dubbed his “Apartment Trilogy”. A conceptual work in which the home, far from being mere background, becomes a mental trap that seizes its prey, fatally separating it from the social context. In a cinema that feeds on enclosed spaces, few like Polanski have managed to elevate domestic walls to full-fledged characters, transforming them into gilded cages or, as here, into psychological crypts. His own biography, marked by loss and nomadism, is mirrored in this recurring investigation into the instability of existential foundations.

Trelkowski is a petty clerk of Polish origin, an insignificant and meek man, almost a shadow, who takes up residence in Paris for work reasons. His foreignness, his being an "other" in a society that observes and judges him, makes him the ideal victim for an aggression that does not occur with physical violence, but with a refined psychological cruelty. The man discovers that the apartment's previous tenant, a certain Simone Choule, had committed suicide by throwing herself from the window. Thus begins a liturgy of discoveries and findings that resurface in the house like vile vestiges of a past that gradually grasps him and drags him into a vortex of madness. Objects, noises, the subtle accusations of neighbors transform into instruments of slow torture, a kind of collective "gaslighting" that undermines his already fragile identity. Trelkowski, passive and acquiescent, embodies the perfect Kafkaesque archetype of the man crushed by an absurd and incomprehensible system, where every request, every oblique glance from the tenants, becomes an unappealable sentence.

The entire narrative and visual structure becomes functional to the protagonist's paranoia while the oppressive sense of claustrophobia assumes intolerable proportions. Polanski, who is also the protagonist here, physically immerses himself in the role, making his performance a tour de force of restrained unease. The camera, often positioned in unusual angles, with wide-angle lenses that distort spaces and oblique perspectives, reflects his mental disintegration. Every shot is a window into his shattered mind. The building's spiral staircase is not just an architectural element, but a spiral descent into the abyss of madness, an inevitable path towards the ineluctable. The sound design also plays a crucial role: the neighbors' noises, night screams, the dripping of water, the breathing of his own anxiety—everything amplifies, contributing to the creation of an atmosphere of constant threat.

Memorable is the scene where Trelkowski visits the girl who had attempted suicide, finding her covered in bandages, an almost Egyptian image of a body mummified before its time. Upon the arrival of a mutual friend, the invalid emits a long scream of terror that Polanski emphasizes with a zoom-in close-up, a dolly shot preceding her wide-open mouth, constricted by the bandages. It is a primordial scream, an omen, almost a warning that transcends time, a voice from the past that anticipates his destiny. That scream is not only the reaction to his vision, but the projection of the terror that will soon seize Trelkowski himself, an echo of his future descent into the same identity.

If in Rosemary’s Baby the terror was of demonic origin, tangible in its satanic wickedness, here it digs into much more ordinary ground, made of routine, daily drabness, moral depravity, and a bureaucracy of cruelty that needs no supernatural entities to devastate. And it is tremendously more unsettling, because it is closer to the reality of our deepest fears: the loss of self, social alienation, the perception of being trapped in a nightmare from which there is no awakening. The absurdity of living, the meaninglessness of human relationships, and the ruthlessness of social judgment are revealed as the true demons, chilling in their banality. Trelkowski, in an act of pathological identification, begins to perceive himself transforming into the unfortunate previous tenant, an obsessive metamorphosis that culminates in a chilling, cyclical, inescapable ending.

Polanski does not merely play with his character's psyche, but invites the viewer to doubt their own perception of reality, to question the nature of identity and its fluidity. The apartment itself becomes a machine for the annihilation of the individual, a stage for an existential drama in which the protagonist is condemned to play a role not his own, a fatality that sucks him into a vortex of self-imposed madness. This is the true “aesthetic shift” in Polanski's poetics: the transition from a horror that, however psychological, still had a lifeline in “reality” (even if macabre), to a purely subjective terror, where the distinction between hallucination and reality is nullified, leaving a sense of vertigo and bewilderment. A work of paramount importance for delving into the poetics of the Polish director and grasping the embryos of a subtle nihilism, of a determinism that leaves no escape, and of a mastery in shaping the unspoken, the elusive terror that inhabits the most recondite folds of the human mind.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...