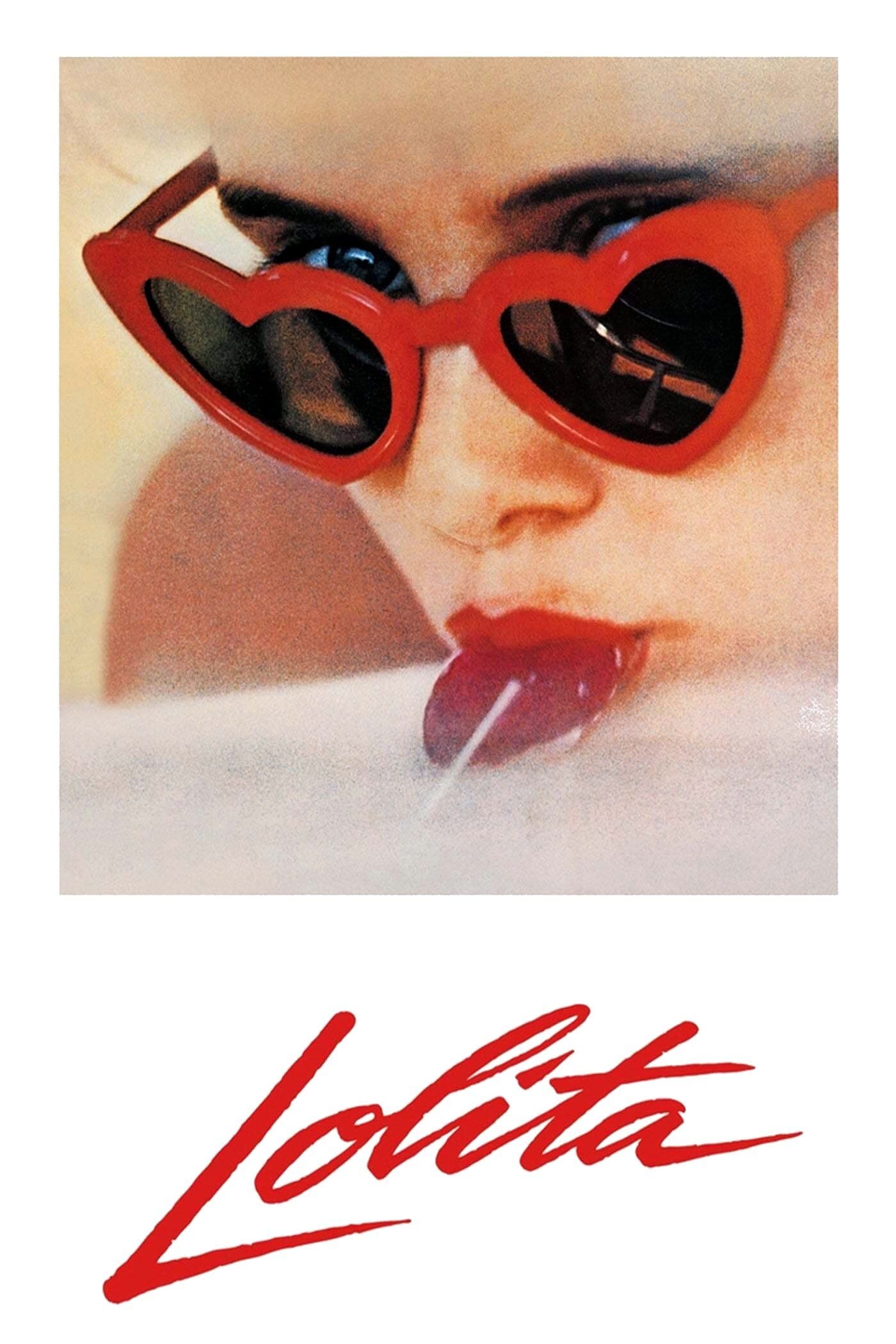

Lolita

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Kubrick re-reads Nabokov and exposes him to the vagaries of his histrionic camera, not merely as an exercise in style, but as a tool to dissect a pathology. That same camera which would later scrutinize the madness of war or spatial alienation, here focuses on an intimate drama, yet one equally universal in its deformity. It is the surgical precision of the Kubrickian gaze, that meticulous attention to detail and composition, that bestows upon the adaptation of Nabokov's novel an almost clinical lucidity, transforming a story of scandal into a disturbing meditation on obsession.

The disruptive sensuality of a fourteen-year-old girl leads to the ruinous downfall of a fifty-year-old intellectual who, having fallen in love with the young girl, marries her mother to be near her. His morbid passion will erupt, traversing the thin line that separates it from madness, a boundary that Kubrick explores with such mastery as to render almost tangible the descent into the inferno of forbidden desire.

It is extraordinary to note how Kubrick acts upon this emotion, highlighting its human and earthly aspects, rather than its sordid immorality (which he willingly leaves to the moralists who condemned the film, failing to grasp its genius). The director, far from wishing to absolve or condemn, chooses the path of psychological understanding, an almost psychoanalytical examination of Humbert Humbert's convoluted mind. In an era still constrained by the rigid strictures of the Hays Code, Kubrick achieves a marvel of evocation, implied and suggested, where Nabokov's book could afford the most explicit of confessions. The prohibition against openly depicting the sexual relationship between adult and minor forced the director to sublimate the unspeakable, to transform the act into an atmosphere, a gaze, an unspoken element that ultimately proves more disturbing than any explicit image. True obscenity, Kubrick suggests, lies not in the gesture, but in the intention, in the persistence of a desire that corrupts the soul.

Sensuality becomes an ethereal game, a joyous amusement interwoven with an animal torment that lingers unconsciously within the man. The young Lolita, played with disarming naturalness by Sue Lyon, is not merely a passive victim here, but an ambiguous figure, an adolescent who embodies both the nymphet idealized by Humbert's perversion and a cunning manipulator, fully aware of her seductive power. This ambivalence is the beating heart of the film, and James Mason's talent in the role of Humbert Humbert manifests in his ability to render the character simultaneously repulsive and pathetic, a man of culture who constantly deceives himself, masking his predatory appetite behind a veil of sick romanticism.

The film, like the book, is entirely centered on this unwholesome passion that Humbert harbors for Lolita, but enriched by the presence of another emblematic figure: Clare Quilty. Peter Sellers, in a chameleon-like and disturbing performance, embodies this degenerate intellectual, playwright, and screenwriter who serves as a grotesque and amplified counterpart to Humbert's depravity. Quilty is Humbert's shadow, his infernal double, who operates without Humbert's intellectual scruples, a pure instance of playful and destructive immorality, elevating the film to a broader satire on the superficiality and latent corruption in provincial America. Their odyssey through the motels and kitsch landscapes of post-war America, a distorted image of the American dream, becomes the setting for a dark tragedy, a road movie where the destination is not freedom but perdition.

The first encounter scene is paradigmatic in this regard: Humbert follows Charlotte on a tour of the house, almost annoyed by the petulant landlady and her shallow chatter, when he sees Lolita in the garden. The girl is sunbathing and looks up at him; immediately, Kubrick cuts to a tight close-up of Humbert, petrified by the vision. It is a moment of distorted epiphany, where the sun, instead of purifying, illuminates a latent corruption. Once shaken from his astonishment, the man rushes to confirm the room rental with Charlotte, who innocently asks him what the decisive factor for his choice was, while Kubrick, at the words “decisive factor,” returns the shot to Lolita's mischievous face and her diaphanous body. It is not just a play of gazes, but a revealing of the soul, the crystallization of an obsession that has found its catalyst.

Through his gaze, Kubrick succeeds in making us grasp the intimate contrast of this dichotomy between animality and decency, between instinct and morality, between transgression and normality, expanding the process of its realization with a solemn and astute mise-en-scène. The black and white cinematography, a masterful work by cinematographer Oswald Morris, highlights the contrasts, the shadows, the apparent purity, and the hidden perversion, imbuing the film with a suspended, almost dreamlike atmosphere. It is a cinematic treatise on the human psyche, a disturbing exploration of how desire can transform into a prison, and how beauty can be both a source of inspiration and of ruin, a masterpiece that continues to provoke and fascinate, transcending its controversial subject matter to assert itself as a timeless inquiry into the darkest depths of passion.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...