Magnolia

1999

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Paul Thomas Anderson, with his third film (after Sydney and the beautiful Boogie Nights), appears as a consummate professional, a director who, in a surprisingly short span of time, has managed to forge a distinct authorial voice, recognizable both in its formal audacity and thematic depth. In Magnolia, he stages a monumental narrative comprised of numerous sub-plots, more or less interconnected, following the model we had already seen and appreciated in Altman's Short Cuts. But while Altman crafted his narrative structure by shaping it around Carver's short stories, with his peculiar, almost anthropological examination of the American human condition, Anderson performs the same operation starting from scratch, conceiving and scripting a story partitioned into multiple subdirectories, like a prism refracted into multiple rays that intertwine, giving form to a narrative that appears whole in its multiplicity, a single granite-like narrative body. This audacious choice is not merely a homage to the master, but a true evolution: Anderson does not limit himself to observing; rather, he delves into the emotional wounds of his characters, seeking catharsis, a form of grace in a world that seems to have lost it. The very genesis of the film is steeped in this creative urgency, born from a period of profound personal reflection by the director.

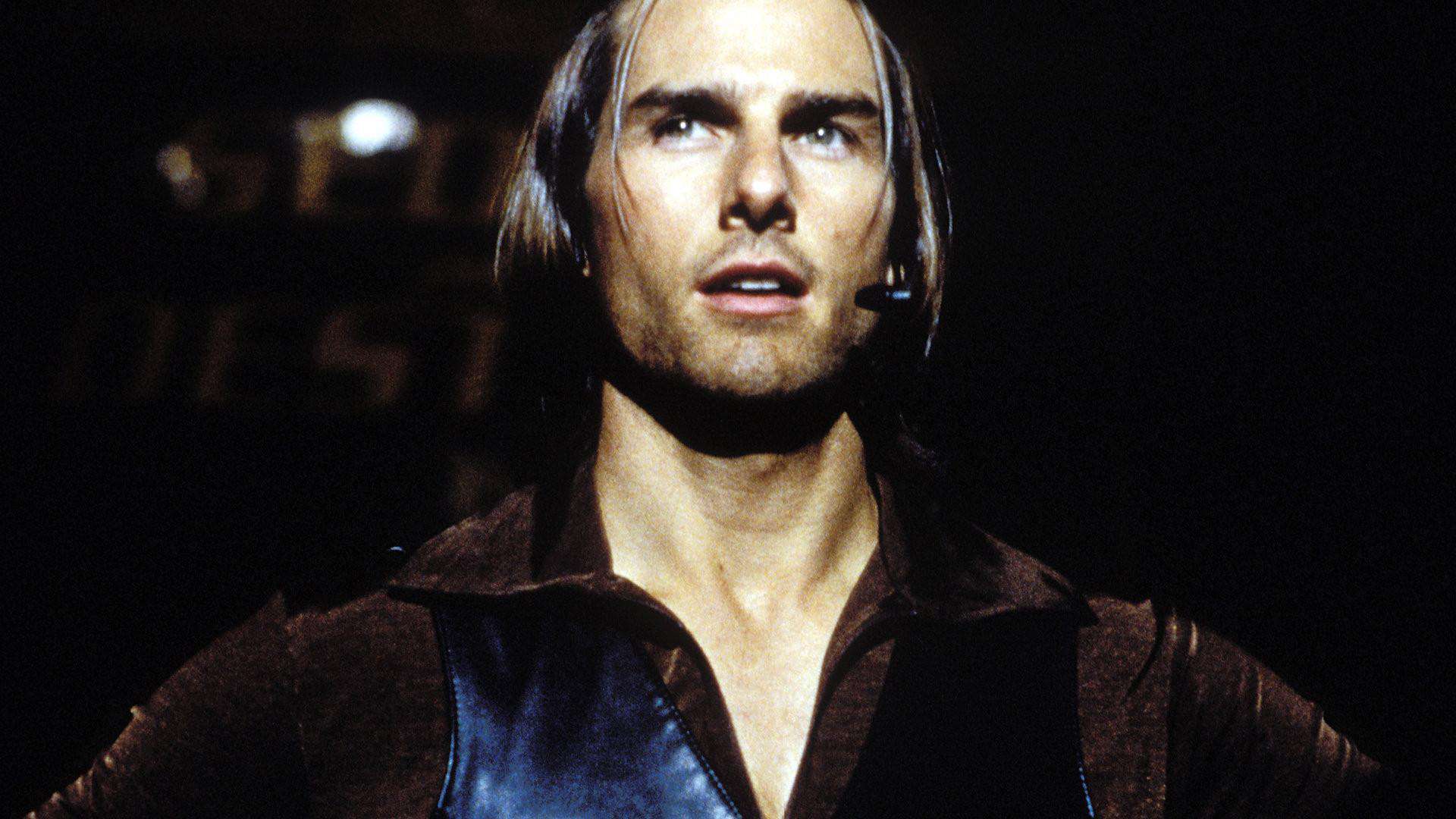

The narrative fabric is further ennobled by great acting performances, such as those by Tom Cruise, who here tackles a role diametrically opposed to his established image as an impeccable hero, demonstrating unexpected vulnerability and ferocity; by Julianne Moore, capable of embodying palpable and heartbreaking despair; and by Philip Seymour Hoffman, here in one of his first significant appearances, already possessing that discreet charisma and subtle depth that would make him a giant. Their ability to bring these tormented souls to life elevates the film far beyond mere formal experimentation.

Magnolia is thus a work studded with a gallery of interconnected characters, a choral fresco that resonates with the echo of intertwined destinies and, often, with the weight of a past that never ceases to exert its centripetal force.

Frank T.J. Mackey is a motivational speaker who teaches men to shake off their inferiority complex towards women and to exercise their innate charisma to conquer them. His figure is an emblem of show-business America, where even masculinity becomes a marketable performance. Behind the façade of ostentatious machismo lies a painful family history, with a father who disowned his son and left home, abandoning him. Now that Frank has been contacted by his dying father's nurse for a final farewell, he finds himself having to confront the demons of his past, an inevitable confrontation with the roots of his own distorted identity.

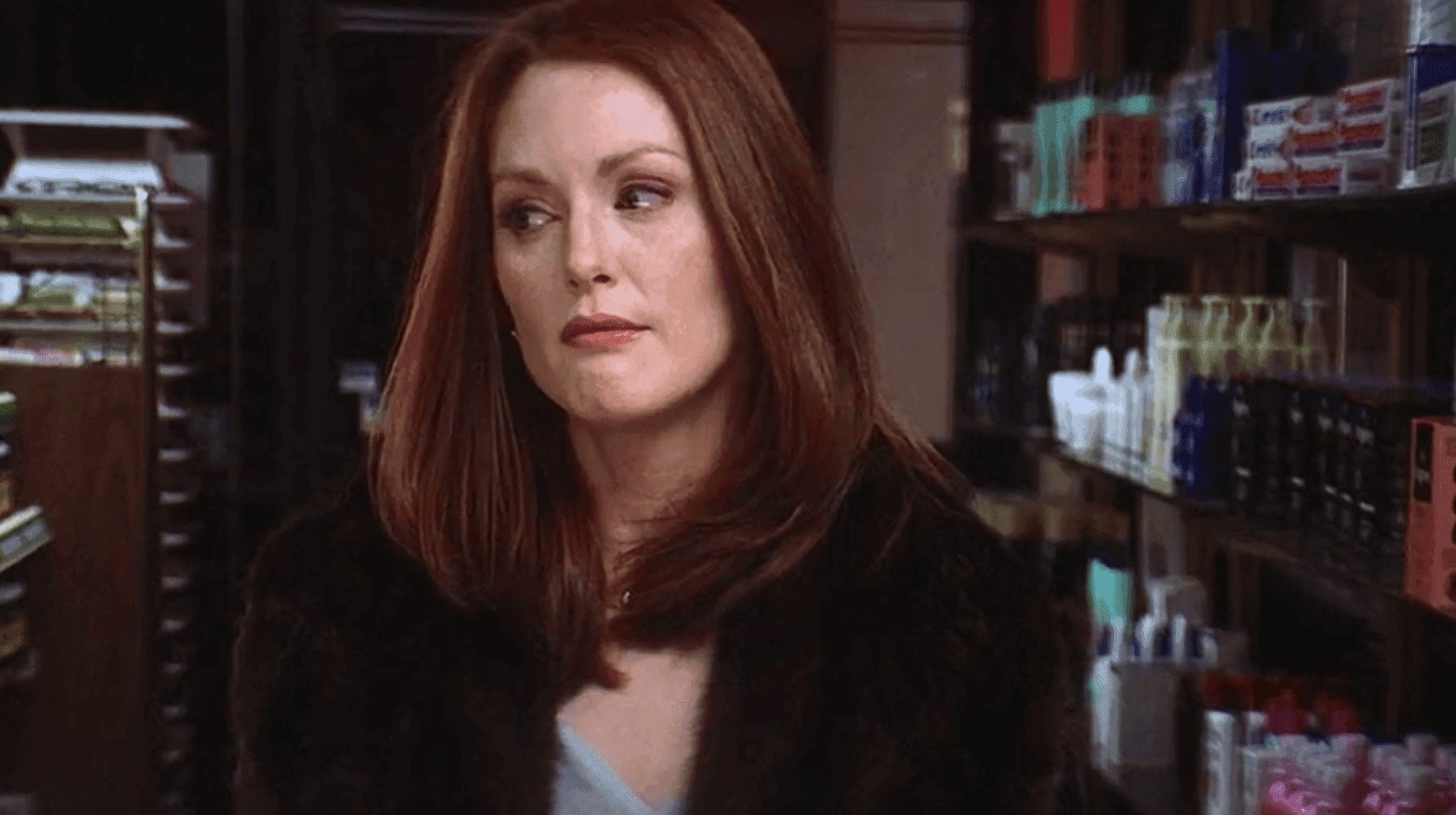

Frank's stepmother and his father's current partner, Linda Partridge, is devastated by guilt for having betrayed her husband; she lives in a deep depression that plunges her into the abyss of drug addiction, discovering she loves her husband only when he is on his deathbed. Hers is a tragedy of regret, the bitter revelation of a dormant affection that only emerges in the face of the irrevocability of loss.

Donnie Smith is a former child prodigy from the successful show "What do Kids Know?", who, after winning a substantial sum of money, has fallen into oblivion. He is tormented by loneliness and a sense of defeat, trapped in a limbo of past glory, and to impress a bartender, he is about to undergo a dental operation, in a pathetic attempt to start over that testifies to his profound insecurity and fragility.

Stanley Spector is a young boy oppressed by a father who forces him to participate in "What do Kids Know?" for money; he feels irremediably sad and alone: he is a young Donnie ante litteram, a predestined victim of that perverse cycle of exploitation and media pressure that seems to be inherited from generation to generation.

Earl Partridge is an old TV lion, presenter of "What do Kids Know" and Frank's father, terminally ill with cancer. On his deathbed, he will discover that he loves Frank, his abandoned son, and his first wife, concluding bitterly that he wasted his life by hurting the people he loved most. His is the tragic realization of a life dedicated to success and not to love, a bitter epilogue that closes a circle of regrets.

Jim Kurring, a divorced police officer consumed by loneliness and an overwhelming sense of duty, meets Claudia, a drug addict whom he tries to help in search of his own redemption. Theirs is perhaps the only glimmer of hope in this universe of despair, a fragile but authentic connection that suggests a possibility of salvation through acceptance and empathy.

This concert of characters, each a dissonant note in a symphony of pain, is interconnected through three registers: suffering, which is a common factor, linking every soul in a universal condition; direct or indirect knowledge through past or present events, an intricate web of relationships and hidden secrets; and, finally, an incredible rain of frogs that enters each of their stories and marks its development. This latter element, the most audacious and debated in the film, transcends narrative realism to touch upon biblical and symbolic chords, an allusion to the plagues of Egypt, an inexplicable event that functions as a purifying cataclysm or, perhaps, simply as a chaotic reset that forces all characters to confront the absurdity of existence and their own vulnerability. It is not a deus ex machina in the classical sense, resolving dramas with ease, but rather a chaos ex machina that shakes foundations and allows for a (albeit minimal) opening towards change.

Magnolia, therefore, is a Moebius strip; the narrative is a loop of pain where characters find themselves having to share their sufferings with people connected to this affliction, in an endless cycle that is, at the same time, a path towards a (often painful) revelation. The masterful use of music, particularly Aimee Mann's songs, is not mere background but an essential narrative element, a kind of modern Greek chorus that expresses the characters' inner lives, culminating in the moving sequence where each one intones "Wise Up," a moment of collective empathy that transcends individual sufferings.

Several scenes are worth highlighting, each a gem of dramatic intensity: from Linda Partridge's devastating fury in the pharmacy, an explosion of a collapsing psyche, to Stanley Spector's silent but powerful act of rebellion, refusing to answer questions on stage, up to the improbable encounter between Jim and Claudia, tender and desperate at the same time. Perhaps the sequence that reaches the highest emotional peak is Frank's dramatic monologue at his father's deathbed, where Frank angrily reproaches him for all his shortcomings before surrendering to a cathartic cry and forgiveness. In that cry, the central theme of the film is condensed: the often vain but always necessary search for authentic connection and some form of redemption, even on the brink of the final, definitive farewell.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...