Manhattan

1979

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Woody Allen rewrites the code of love in a metropolitan key with a delicate narrative enhanced by a polished black and white. This aesthetic choice is not merely stylistic; it is a programmatic declaration that elevates Manhattan from a simple backdrop to a tangible, almost mythological character, a stage for the intellectual neuroses and sentimental afflictions of the New York bourgeoisie. The polished chromatism of black and white, in an era when color was the norm, evokes an immediate resonance with cinematic classicism, with the splendors of a bygone Hollywood, but also with the sober elegance of neorealism or the visual suggestions of film noir, imbued with an underlying disquiet that permeates relational dynamics.

The result is a film that borders on comedy and an intimate diary, flowing like a single powerful poetic piece. It is not a romantic comedy in the conventional sense, but rather a bittersweet anatomy of contemporary emotional complexities, a deep dive into the existential anxieties and self-mystifications that define the protagonists. Its rhythmic, almost musical pace, marked by sharp dialogues and contemplative walks through iconic streets, makes it an almost synesthetic experience.

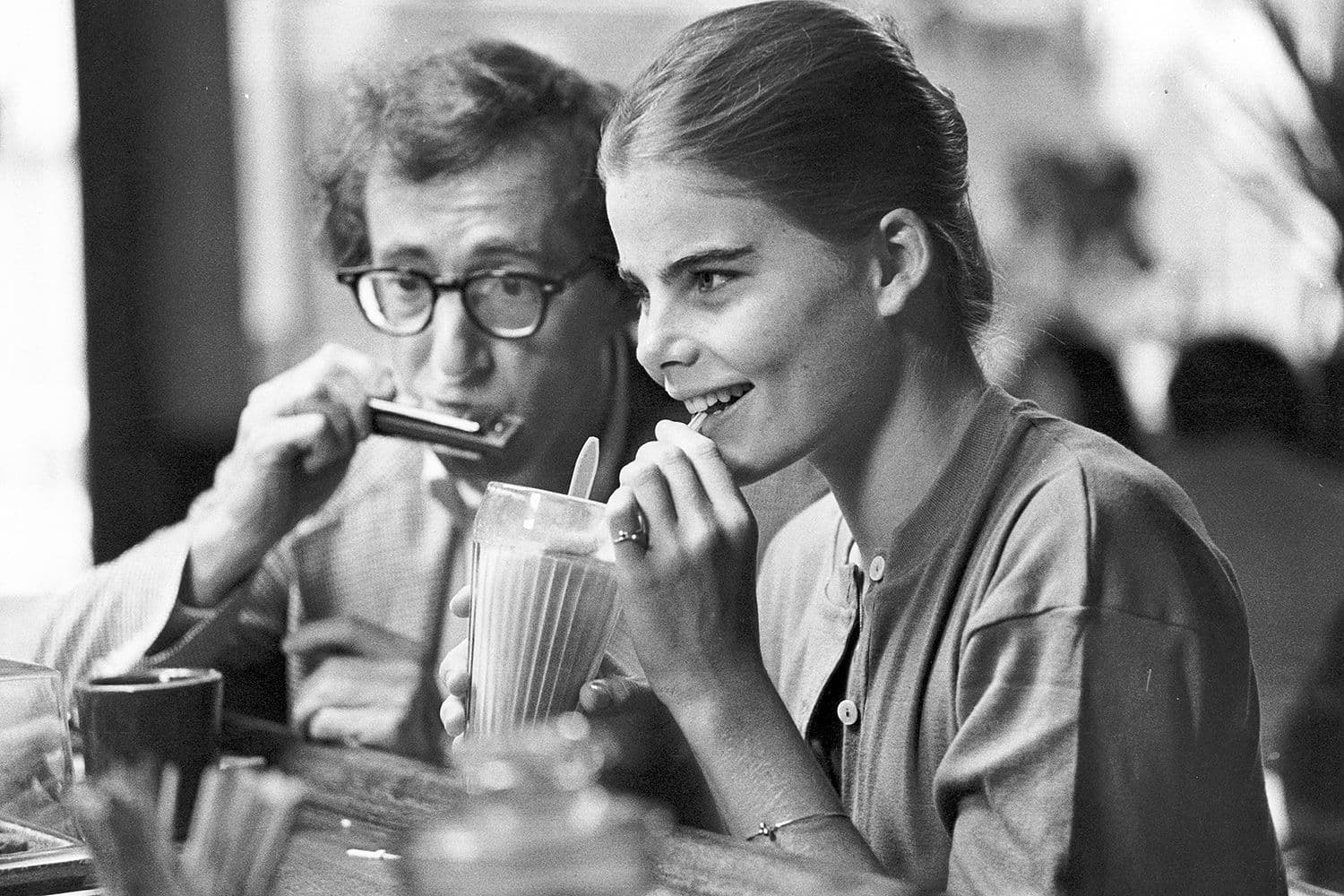

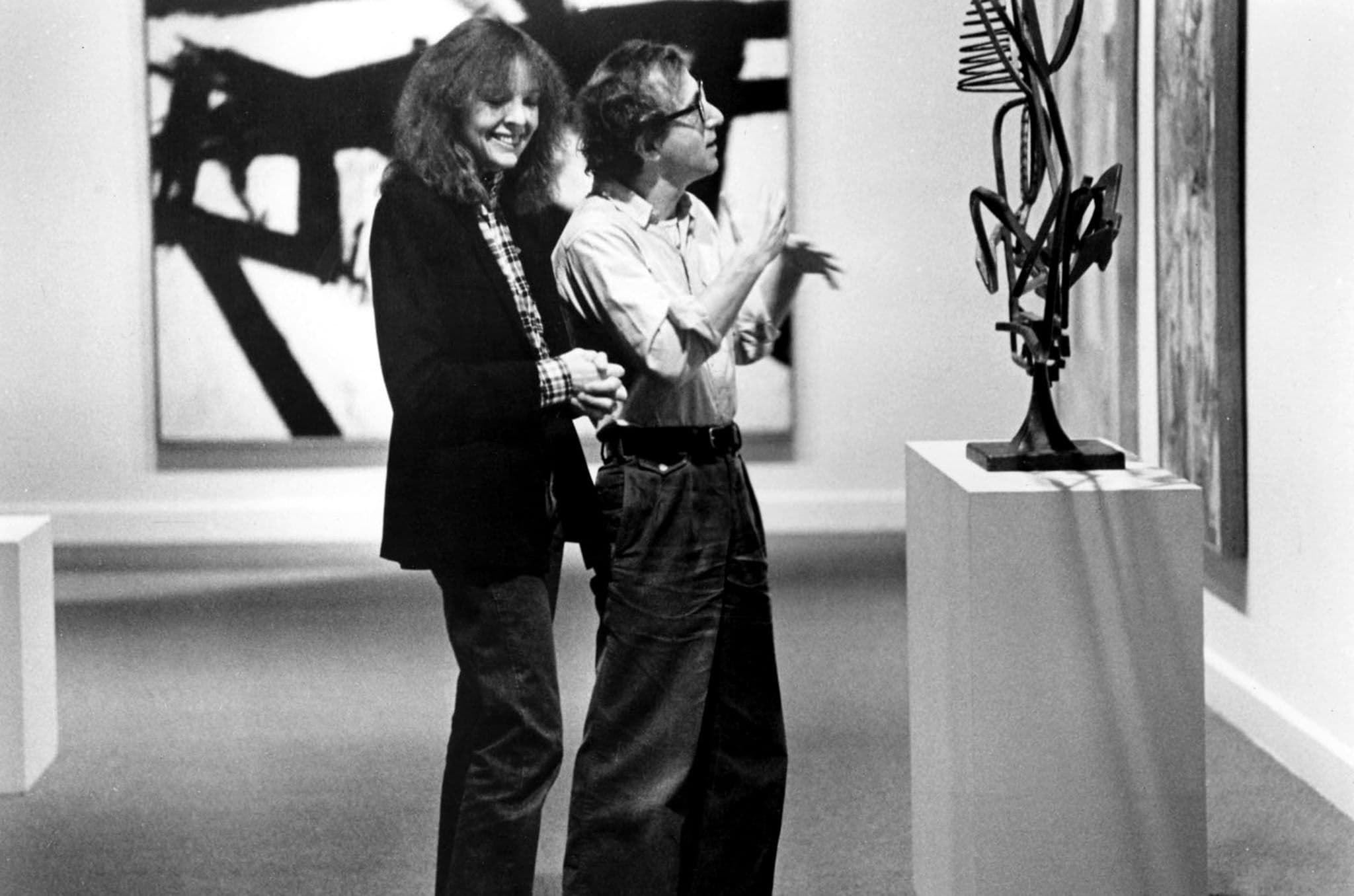

The story is that of Isaac, a forty-two-year-old TV screenwriter, who has just divorced Jill. His ex-wife is writing a memoir with embarrassing details about their private life, a gesture that not only exacerbates his already fragile self-esteem but raises questions about the nature of privacy and the commodification of personal experiences in the modern era. Isaac, meanwhile, tries to rebuild his life with a seventeen-year-old, Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), a relationship that, though imbued with unexpected sweetness, is constantly undermined by his pathological intellectualism and chronic insecurity, in a perpetual moral dilemma that condemns him to an unresolved search for an "adult" and "intellectual" love. But it is the arrival of Mary Wilke (Diane Keaton), his best friend Yale's (Michael Murphy) lover, that throws Isaac into a labyrinth of forbidden passions and vitriolic conversations, amidst sharp irony and intellectual pretensions that mask an evident emotional confusion. The four-way relationship between Isaac, Tracy, Mary, and Yale, an intricate waltz of betrayals and uncertain loyalties, becomes a mirror of a society that confuses analysis with action, idealization with feeling.

A long song to lost love and latent happiness. Love here is an elusive concept, a promise constantly evaded by self-sabotage and an unattainable idealization. It is a work pervaded by that bitter cynicism infused with irony that only Allen can impart, yet an intimately lyrical film. This peculiar fusion of cynicism and lyricism is the quintessence of his style, a unique ability to find comedy in tragedy and poetry in everyday banality. The film does not offer easy answers but delves into the complexity of human relationships with disarming sincerity, though veiled by a salvific self-irony. Isaac's intellectualism, his tendency to philosophize about every aspect of life, ultimately becomes both his cross and his salvation, a way to defend himself from vulnerability while ardently desiring it.

There are many memorable scenes, as well as lines that have entered the collective imagination, but as far as we are concerned, the film's opening is something wonderful. It is not just an new beginning; it is a declaration of intent, a microcosm that encapsulates the entire soul of the work. As images of Manhattan, draped in exquisite black and white, unfold, the notes of George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue emerge, an orchestral anthem to the grandeur and frenzy of the metropolis, an explosion of sound that perfectly merges with the impressiveness of the visuals. The choice of Gershwin is not accidental: it evokes a golden age, a romanticization of the American past, and in some way anticipates Isaac's idealization of the city. Interspersed with the music, Isaac's words, read in his unmistakable tone of voice, create a brilliant counterpoint: “Chapter One. “He adored New York. He idolized it immoderately…” No, it's better “he romanticized it immoderately,” that's it. “To him, in any season, this was still a city that existed in black and white and pulsed with the great melodies of George Gershwin…” No, let me start over… Chapter One. “He was too romantic about Manhattan, as he was about everything else: he found vigor in the feverish comings and goings of the crowds and the traffic. To him, New York meant beautiful women, sharp guys who seemed broken from any navigation…” This self-correction, this narrative insecurity, this incessant attempt to find the perfect word to describe an idealized love for the city, not only reveals Isaac's obsessive and neurotic character but also serves as a metaphor for the artistic struggle itself, for the difficulty of capturing the essence of life in words. It is a prologue that is simultaneously a portrait of the protagonist, a declaration of love for the city, and an essay on the art of writing, a metalinguistic game that invites the viewer to reflect on the nature of narration and the construction of reality. Manhattan is not just a film; it is an ode, a confession, a cinematic monument to love and life, seen through the unmistakable lens of a genius of neurosis.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...