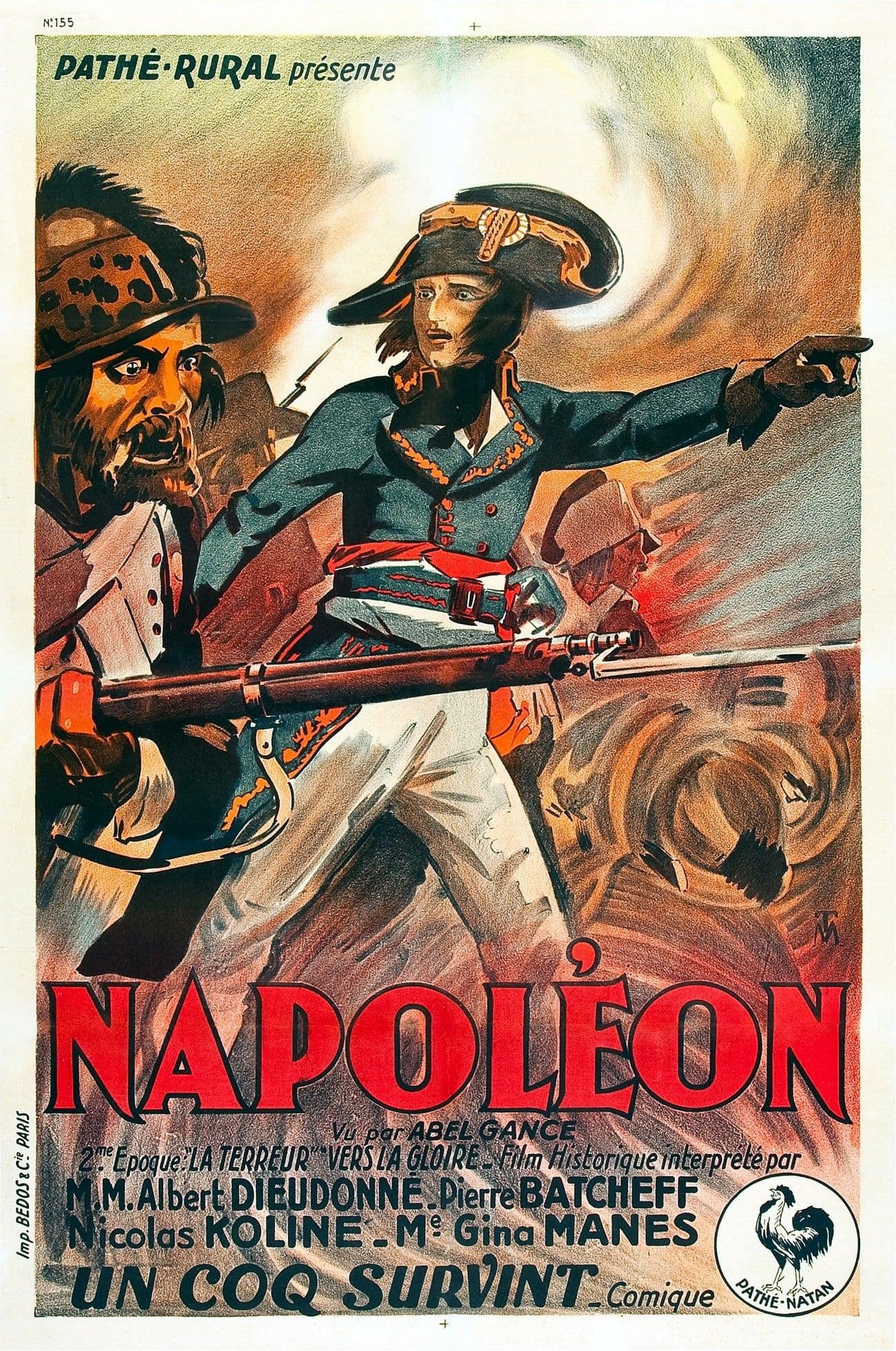

Napoleon

1927

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Abel Gance's Napoleon is a feverish dream of history, a visionary delirium lasting almost six hours that attempts to capture the biography of a key historical figure, but also the soul of an era. Seen today, almost a century after its release in 1927, it does not appear dated, but rather like an artifact from a future of cinema that we have not yet reached. It is an act of such crazy technical ambition and such bold romantic fervor that it makes most contemporary blockbusters pale in comparison, reducing them to timid exercises in style.

Gance does not merely codify the historical biopic; he effectively invents the mythopoetic biopic. His interest is not in the pedantic accuracy of documentary, but in the creation of a myth, the transfiguration of a man into a symbol. His Napoleon, played by Albert Dieudonné, whose resemblance to the real emperor is disturbing to say the least, is not just a general or statesman. He is the embodiment of the spirit of the French Revolution, a force of nature, a romantic hero with the soul of a Victor Hugo character and the impetus of a Plutarchian leader. The famous opening sequence, with the snowball fight at the military college in Brienne, is a miniature symphony of the entire film: the young Napoleon, already a misunderstood and opposed tactical genius, leads his companions to victory with the same determination with which he will lead the Army of Italy. Gance does not show us a child, he shows us the Emperor in the making.

The great challenge was to portray such a historical figure through the medium of silent cinema, a cinema devoid of words, of the Word that was one of Napoleon's weapons. Gance responds to this challenge with an explosion of purely visual language, unleashing an arsenal of technical innovations that still leave us speechless today. His mobile camera becomes an active character, a hungry witness throwing itself into the heart of the action. During the scene of the “Marseillaise” or the storming of the Convention, the camera is handheld, shaking and jostling in the crowd, conveying the fervor and chaos of the Revolution in an almost physical way. To depict Napoleon's escape by boat from Corsica during a storm, Gance tied the camera to a pendulum, creating a cinematic experience of seasickness that was disconcertingly realistic. His was an authentic immersion in historical reality, allowing the viewer to experience it firsthand.

The apotheosis of this experimentation is the famous finale, shot using a technique he christened Polyvision. Using three cameras side by side, Gance creates a triptych that projects three distinct images onto three screens, anticipating Cinerama and widescreen by decades. This is not just a gimmick for film nerds. It is an aesthetic and philosophical choice. Sometimes, Gance uses the triptych to create a breathtaking panoramic image, a visual horizon finally large enough to contain the ambition of Napoleon looking towards Italy. At other times, he uses it to create a simultaneous montage, a symphony of images that juxtaposes the close-up of his hero, the eagle symbolizing his destiny, and the marching troops. It is the simultaneity of thought, vision, and action made visible. It is cinema becoming pure poetry.

Abel Gance was a central figure in the avant-garde movement known as French Impressionism in the 1920s, but his ambition drove him further. If parallels are to be drawn, he can be compared to D.W. Griffith, whose epic scale of works such as Intolerance he admired, or to Sergei Eisenstein, his contemporary and rival. But where Eisenstein's editing is intellectual, dialectical, a hammer that forges an idea in the viewer's mind, Gance's is emotional, lyrical, a raging river that overwhelms the senses. His Napoleon is the anti-Battleship Potemkin: it is not a celebration of the masses, but the apotheosis of the exceptional individual, the man of destiny who bends history to his will.

It is fascinating to compare Gance's historical vision with subsequent major film projects dedicated to Napoleon. The most famous is obviously Stanley Kubrick's unfinished project, perhaps the greatest “lost film” in history. Kubrick's would have been the anti-myth par excellence. Based on obsessive historical research, it would have demystified the figure of Napoleon, showing him as a military genius but also as a man full of psychological contradictions, a bureaucrat of war, a tyrant whose victories were based on impeccable logistics and a ruthless indifference to human life. It would have been a cold, analytical, deeply anti-romantic work. More recently, Ridley Scott's Napoleon has taken a middle ground. Despite Scott's usual mastery in staging spectacular battles, his film focuses on a more intimate and at times almost caricatural portrait, focusing on Napoleon's relationship with Josephine and painting a leader who is almost clumsy and socially inadequate.

It is a valid approach, but it lacks both the mythopoetic fury of Gance and the intellectual rigor that Kubrick would have brought to the table. This comparison only serves to highlight the unique and unrepeatable greatness of Gance's film. His work is not a historical document; it is history itself becoming an opera, a daydream projected onto a screen.

It is a testament to an almost insane faith in the power of cinema to not merely record the world, but to reinvent it, to infuse it with an epic and mythological breath. For its boundless ambition and for its innovations that showed cinema a path that we still struggle to follow today, Napoleon is not just a film to see before you die, it is an experience that leaves you changed.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...