Nosferatu

1922

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

With Murnau's Nosferatu, a language, a taxonomy of images, was configured for the first time, which soon became a reference Grammar for all subsequent Cinema: a semantics with which to conceive and construct new grand celluloid cathedrals. That language, that taxonomy of images, was invigorated by the very lifeblood of German Expressionism, a movement that aimed to project onto the big screen not only objective reality, but the distorted inner perception, the hidden anguish of the soul. All of this was made possible by the visionary genius of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. The great German director thus managed to forge an innovative visual language, characterized by expressive framing, interplay of light and shadow, and a masterful use of set designs that deform reality to reveal its darkest essence. The film's visual impact remains extraordinary today, a testament to its ability to evoke terror through pure form.

It is also important to remember that Murnau made the film without the rights to Bram Stoker's work, Dracula. This choice forced him to modify some elements of the plot and characters, but also allowed him to give his own interpretation to the vampire myth, transforming Dracula into Nosferatu, a more unsettling and less romantic character. The forced expedient of circumventing the rights to Bram Stoker's work, Dracula, by transfiguring the Count into the repulsive Orlok and his name into Nosferatu – from ancient Greek νοσοφόρος, nosophoros, meaning disease-carrier – was a blessing in disguise. Not a mere legal necessity, but an act of creative liberation that allowed Murnau to disanchor himself from the novel's Gothic linearity, to forge an archetype of primal terror. Murnau's Vampire is a grotesque and monstrous figure, embodying man's deepest fears: not an aristocratic seducer, but a repulsive parasite, a carrier of pestilence, similar to a rodent that infests and destroys.

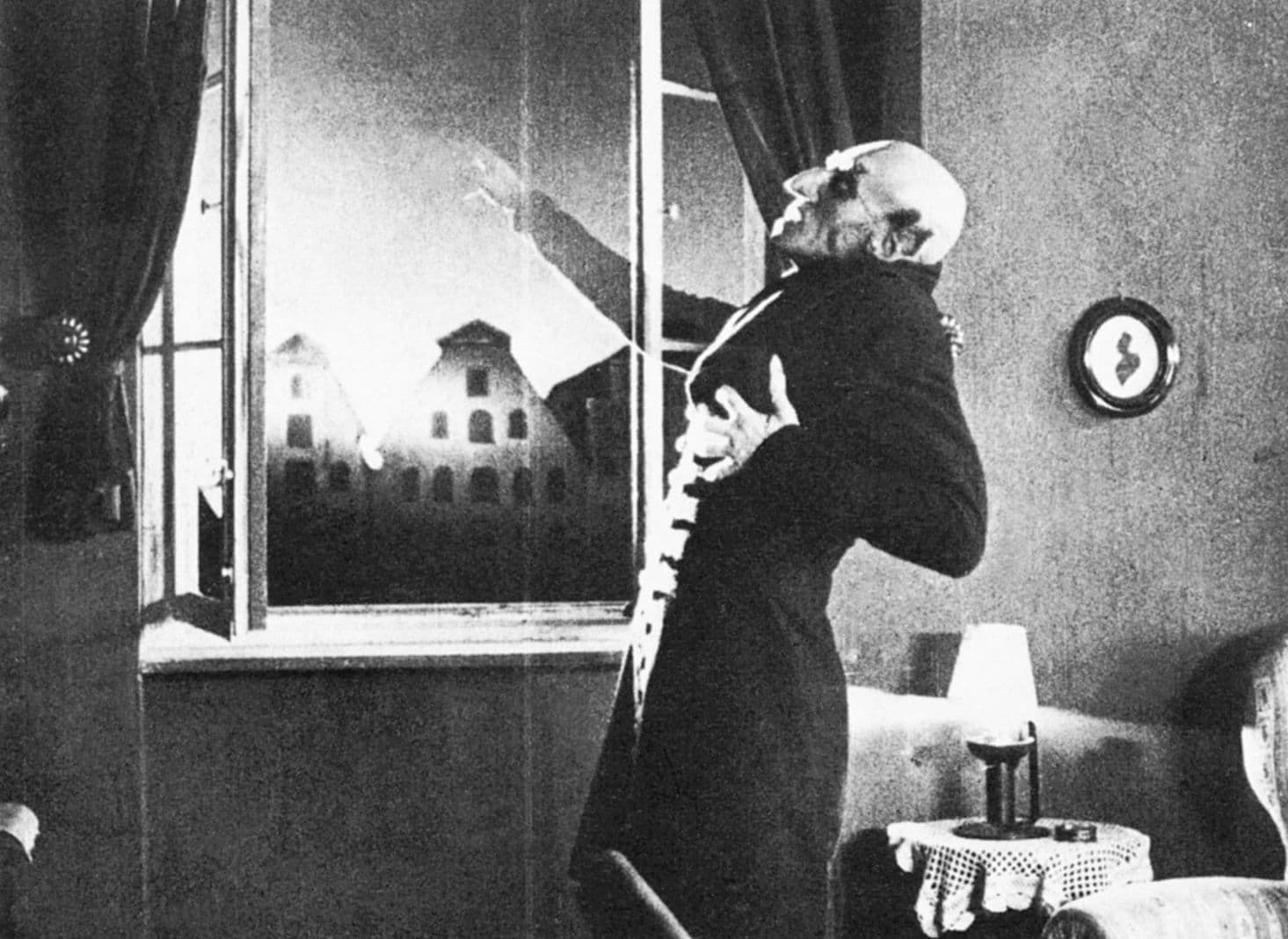

The film's atmosphere is somber and oppressive, creating a sense of anguish and unease in the viewer. Murnau perfectly conveys the horror and fear that characterize the vampire myth, elevating them to an almost metaphysical dimension. Murnau did not merely paint with light; he sculpted darkness. His use of chiaroscuro, borrowed from the Baroque painting tradition but reinvented for cinema, was not merely an aesthetic artifice, but a narrative tool that conferred psychological depth and a sense of inevitability. Sequences shot in negative, where white becomes black and vice versa, transform natural landscapes into nightmarish visions. The use of stop-motion for filming Orlok's advance, while giving him an unsettling, unearthly swiftness, serves to emphasize his nature alien to human time, while superimposed images create an eerie spectral aura that precedes him.

Murnau drew inspiration from the works of Expressionist painters like Munch and Kokoschka, creating a visual aesthetic strongly influenced by figurative arts, but also by the scenographic architecture that exaggerates lines, deforming spaces to reflect the characters' state of mind and the latent unease. The film is rich in symbols: Orlok's castle represents the unconscious, the fog is a symbol of death advancing inexorably, the sun represents life and hope, whose rising is the only weak weapon against the shadow of evil. The film's narrative structure is simple and linear, yet at the same time rich in psychological nuances. Nosferatu's progressive invasion of the quiet town of Wisborg creates a crescendo of tension that culminates in an apocalyptic finale, an epiphany of evil that is vanquished not by a heroic act, but by innocent sacrifice.

Wisborg, Germany, 1838. Young real estate agent Thomas Hutter is tasked with concluding a deal with a mysterious Transylvanian client: Count Orlok. Unaware of the Count's true nature, Hutter travels to his gloomy castle, where he is greeted by an atmosphere of death and decay. Orlok, a monstrous and ancient being, is drawn to Hutter's blood and decides to follow him to Wisborg. Meanwhile, in the quiet German town, strange events begin to occur: inhabitants fall ill and die under mysterious circumstances. Orlok's shadow looms over the city, sowing terror and despair. Hutter's wife, Ellen, senses the danger and tries in every way to protect her husband and her community. Orlok, a living embodiment of horror, represents the personification of man's deepest fears: death, illness, isolation. His figure, graceful and at the same time grotesque, is an allegory of madness and destruction. Max Schreck's portrayal of Orlok is legendary. His emaciated physique, clawed fingers, pointed ears, and sunken eyes, combined with his rigid and spectral gait, were not the result of simple stage tricks, but of an almost sacrificial metamorphosis. Schreck did not 'act' Orlok; he 'embodied' him, to the point that popular legend, also fueled by the film Shadow of the Vampire, whispers that the actor himself was a true vampire, lending an authenticity to the role that transcended fiction.

This work was not just a horror film; it was a distorting mirror of Weimar Republic Germany, a country scarred by the wounds of the Great War, afflicted by economic crises and a profound sense of disorientation. Orlok, with his inexorable advance and trail of death, could be read as the personification of the epidemics that had decimated Europe (the memory of the Spanish flu was still vivid), or as a metaphor for the social and moral collapse that seemed to threaten the nation's foundations. The struggle between Hutter and Orlok becomes a metaphor for the battle between good and evil, between light and darkness, but above all between life and decomposition. As Orlok draws ever closer to Wisborg, the town's inhabitants unite to try and defeat the monster, in an act of desperate and ultimately vain resistance against an entity that cannot be confronted by conventional means.

Famous is the scene of the hearse launched into a mad dash through the night, or the evocative sequences of the Count's shadow, with its eerie claws, looming on walls consumed by darkness, almost a physical entity presaging his very presence. These images rightfully entered the iconography of terror, influencing generations of filmmakers. Murnau's Nosferatu has inspired numerous directors, from Werner Herzog with his philological homage in Nosferatu the Vampyre, to Francis Ford Coppola with his more romantic Bram Stoker's Dracula, and continues to be an inescapable reference point for all those interested in horror cinema and Expressionist cinema. Its tormented production history, marked by the almost complete destruction of all original copies following the lawsuit filed by Stoker's widow, makes its survival a minor miracle, a testament to the resilience of art. A stratified and constant cultural legacy that has left its indelible mark on our collective imagination and on the Art of Cinema tout court, demonstrating how the purest terror often lies in allusion, atmosphere, and the evocative power of the image.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...