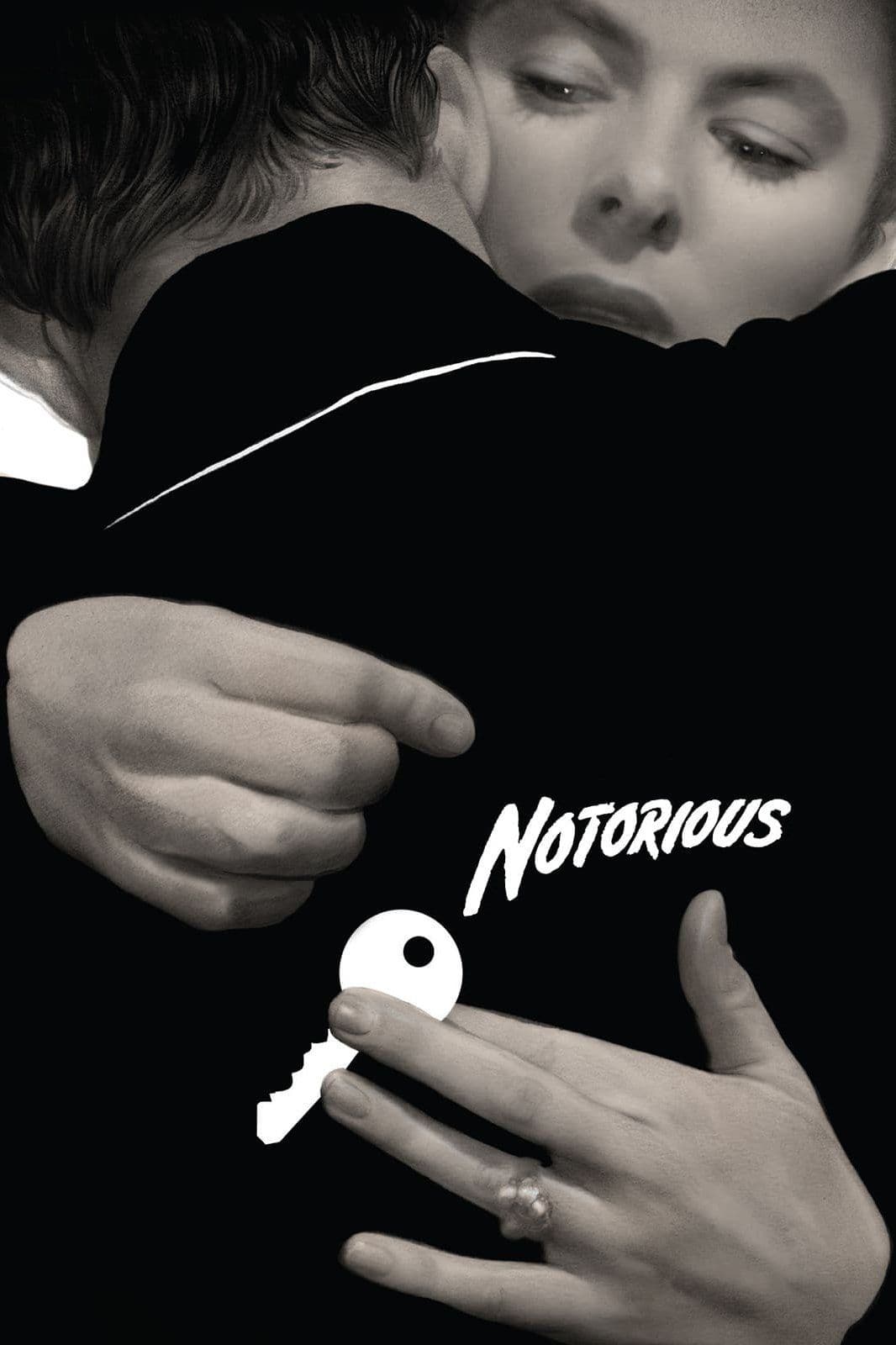

Notorious

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Hitchcock directs with unparalleled stylistic refinement, combining his directorial mastery with a compelling story and an engaging narrative progression that transcends the mere mechanics of the thriller to delve into the labyrinthine dynamics of the human psyche. His ability to manipulate the viewer's gaze, guiding them through a kaleidoscope of emotions and suspense, is here elevated to pinnacles of cinematic perfection. Every shot is not only functional to the plot, but an essential piece of a visual architecture that communicates moods, hidden intentions, and imminent dangers, transforming the medium into a truly immersive and palpable experience.

In the aftermath of the World War and at the dawn of the Cold War, Hitchcock firmly maintains his focus on the Nazis, still considered villains par excellence, but places them in a post-war context that insinuates new fears, those of a silent and insidious enemy, concealed within the fabric of civil society. Notorious emerges as a bridge between the overt anxieties of the recently concluded conflict and the long, latent shadow of an atomic and espionage era, where the threat no longer manifests on the battlefield but in bourgeois drawing rooms, in the hidden depths of a cellar, in the smoke of a poisoned cigarette. It is the beginning of a new kind of terror, intimate and psychological, which the master of suspense anticipates and crystallizes on screen, transforming uranium into a terrifying MacGuffin that amplifies the characters' fragilities and the precariousness of a world on the brink.

In this tense scenario, a woman, Alicia Huberman, is infiltrated into the home of a uranium smuggler on behalf of the Nazis, on a mission that proves to be much more than a simple espionage task. It is a journey into the dark heart of betrayal, compromised morality, and, ultimately, redemption. Alicia, an embodiment of the "woman with a past" so dear to Hitchcock, is forced to navigate a labyrinth of deceptions, sacrificing her dignity and her life for a cause imposed upon her. Her fragility and strength emerge in a precarious balance, making her one of the most complex and unforgettable female characters in his cinematic universe.

Love and death intertwine in a breathtaking crescendo, where the line between passion and danger becomes increasingly blurred. The romantic triangle between Alicia, the cynical agent Devlin, and the tragic villain Sebastian is not merely a narrative device, but the emotional core of the work. The film explores the ambivalent nature of love, which can be both a tool for salvation and for manipulation. Devlin, tormented by his inability to fully trust Alicia, embodies the moral ambiguity of the Cold War, where even "heroes" are forced to make ethically questionable choices. Sebastian, on the other hand, is a tragic character whose pathetic and obsessive love for Alicia leads him to an inevitable ruin, another collateral victim of a game of power and deception that extends far beyond his personal dimension.

Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman merge into their roles with palpable chemistry, in a boundless love that defies all convention and censorship. Their performance is not only masterful, but transcends acting to become a true fusion of icons. Grant, with his aplomb and natural elegance, conceals beneath the surface a deep vulnerability and an inner conflict that makes his Devlin extraordinarily human. Bergman, with her vulnerable beauty and emotional intensity, imbues Alicia with a depth that elevates her from a mere pawn to a tragic and heroic figure. The famous "interminable kiss" sequence, which shrewdly circumvents the Hays Code restrictions by dividing the act into brief effusions interspersed with dialogue, is a manifesto of the intimacy and erotic tension that permeates their relationship, a testament to how the master knew how to circumvent limits to express the inexpressible.

The sequence of the cellar key disappearing from the bunch and then reappearing the next morning is famous. This small, insignificant object, the MacGuffin within the MacGuffin, becomes a powerful generator of suspense, a striking example of Hitchcockian "pure cinema." The threat does not lie in the key itself, but in the terror that its absence might have been discovered, in the imminent risk of a fatal revelation.

Hitchcock's maniacal attention to detail is a distinctive signature of his genius. Every scene was drawn by him in a storyboard before being filmed; every single detail of the scene, every shot, was designed, drawn, and then filmed with almost obsessive precision. He left nothing to chance, orchestrating every camera movement, every expression, every prop with the precision of an orchestra conductor. This meticulous planning, which often made filming an experience of pure execution for the actors with no room for improvisation, guaranteed total control over the final result and the viewer's emotional reaction, demonstrating his conviction that the film should be "finished in his head" even before shooting began. It is this creative tyranny that allowed him to sculpt suspense frame by frame, guiding the audience's gaze and emotions with a firm and invisible hand.

In this sense, the film's opening scene is paradigmatic, where Devlin is always filmed from behind as he observes Alicia, whose father was convicted of espionage that very day, drinking and flirting to distract herself from the thought of her condemned parent. The camera, placed behind Devlin's head, only captures the woman as she approaches and speaks to Devlin. This directorial choice is not accidental: by positioning the camera behind Devlin's back, Hitchcock forces us to share his judgmental gaze, to see Alicia through the filter of his distrust and disappointment. The glass Alicia raises to her lips is not only a gesture of despair, but a symbol of her refuge in hedonism, a mask for pain and shame.

A perfect scene where Alicia's unseemly behavior is perfectly stigmatized by the cynical gaze of a camera that almost serves as a moralizing element, inviting us to participate in the judgment before guiding us toward understanding and empathy for her complex figure. It is not merely cynicism, but a masterful introduction to her moral dilemma and vulnerability, which the film will explore and subvert throughout the narrative. This filming technique, which would later be widely used in first-person scenes to immerse the viewer in a character's perspective, for those years, as is easily understood, represented an absolute innovation, a leap forward in the construction of psychological suspense and the art of making the audience complicit in the emotional experience on screen. Its influence is discernible in countless subsequent works, testifying to how Notorious is not only a masterpiece of its time, but a milestone in the evolution of cinematic language.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...