Paris, Texas

1984

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

The last film in Wenders' American cycle (after The American Friend and Hammett: An Investigation in Chinatown) was born from an encounter with Sam Shepard, a versatile actor with a penchant for dramaturgy (we recall his collaboration on the screenplay for Antonioni's Zabriskie Point in 1970). This synergy between the European auteurial vision and Shepard's profoundly American soul, his intimate connection to the myths of the frontier and the existential solitude that permeates the landscape, is the lifeblood of a work that transcends genre. Wenders, fascinated by the West as a space for escape and reflection, found in Shepard not only a co-screenwriter but a true narrative accomplice, capable of imbuing authenticity into the drama of the wanderer and his relationship with a vast and implacable nation.

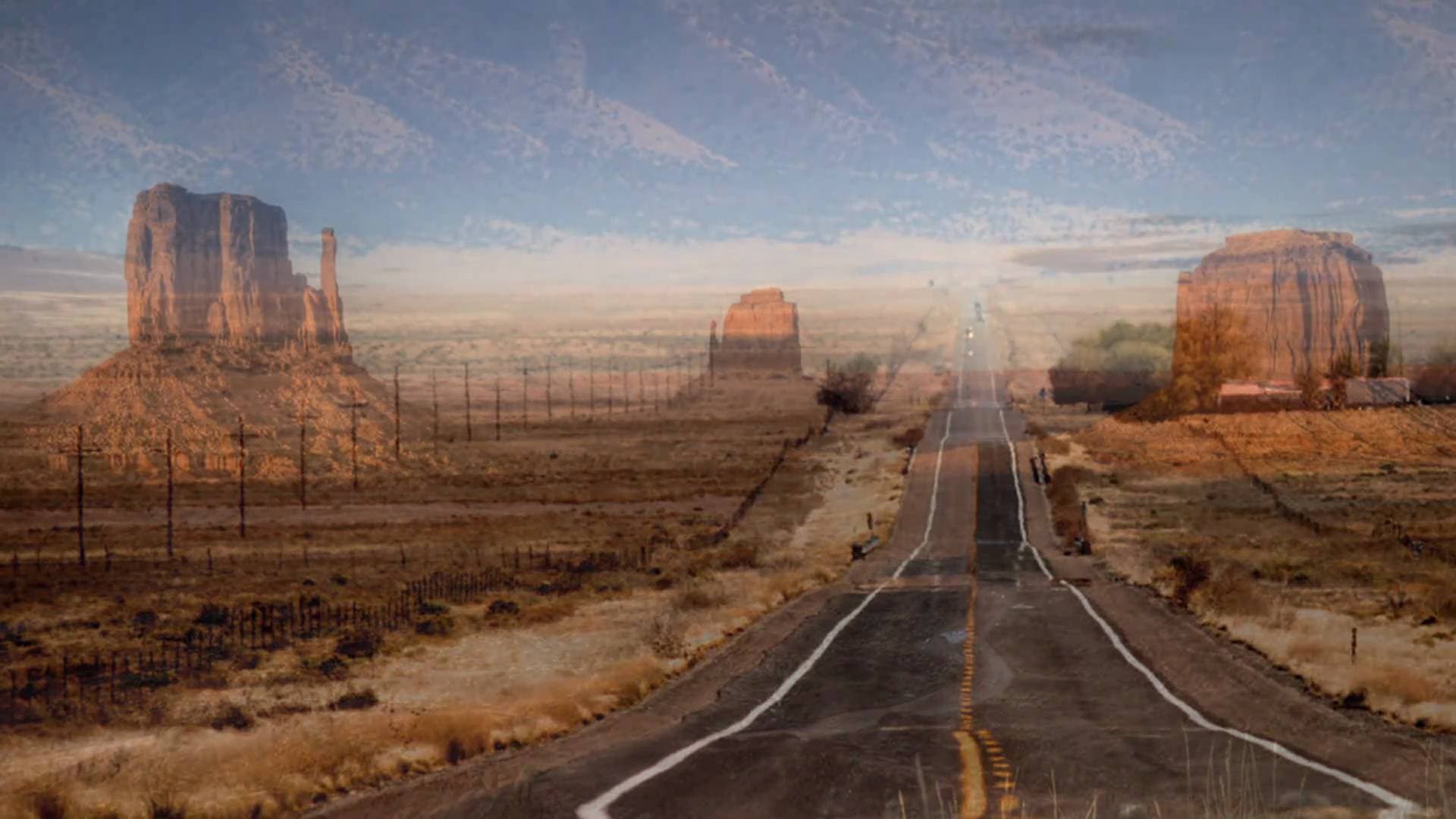

The result is an intimate and melancholic road movie, one of the German director's most beloved films, a visual elegy that unfolds across the boundless spaces of Texas and anonymous urban peripheries. The work is inscribed within a cinematic tradition that views travel not merely as geographical displacement, but as forced introspection, akin to a Rossellinian Journey to Italy transfigured in the aridity of the American desert. Robby Müller's camera, Wenders' long-time collaborator, becomes an accomplice to this melancholy, capturing the pastel hues and long shadows that evoke a sense of loss and poignant beauty, a landscape that is as much physical as it is internal.

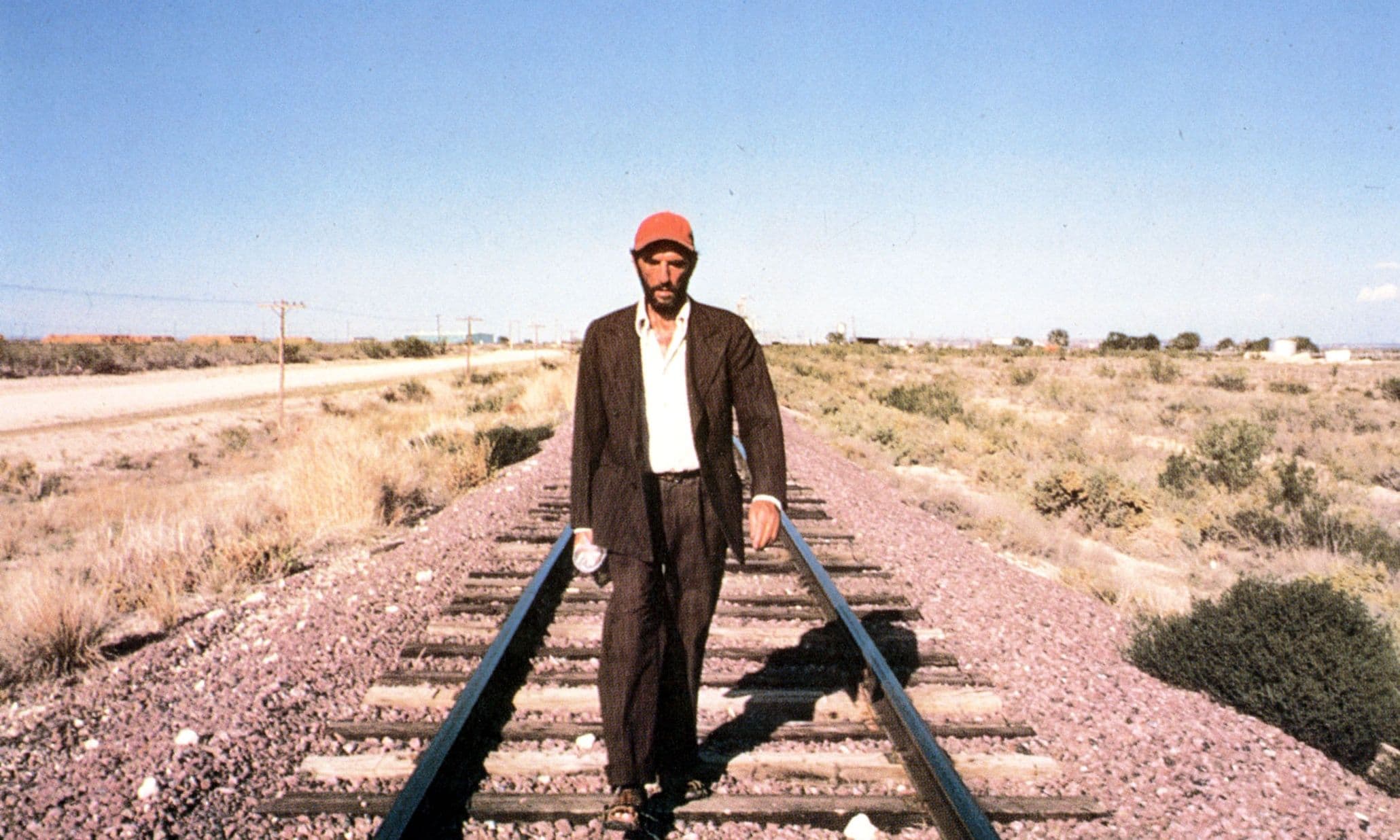

A man wanders alone and aimlessly in the desert, without memory, a kind of existential tabula rasa moving through a primordial landscape. His name is Travis and he appears to be in a state of confusion. This amnesia is not a mere narrative device, but a powerful metaphor for the rejection of past pain, an attempt to erase the self to escape the memory of one's misdeeds. Gradually, he will reconstruct the subtle thread of existence, being recovered by his brother and brought back to Los Angeles. The return to civilization is a confrontation with what he left behind, a gradual re-emergence of consciousness.

Here he reunites with his son, Hunter, who, after his parents' separation and abandonment, lives with his aunt and uncle. Initially, communication between them will be difficult; too many things have been left unsaid, too many silences have carved an abyss. Their bond is fragile, broken, but the irrational force of filial and paternal love slowly begins to re-tie the threads. Travis, with an almost mute obstinacy, seeks contact, a bridge toward a child who is the last anchor of his identity.

Gradually, Travis will manage to break through to Hunter and find such a rapport as to involve the boy in a project: to find his mother, lost in the sands of time. Their odyssey transforms into a shared quest, an initiatory pilgrimage in which the son, with his purity and lack of judgment, becomes guide and motivation for the father. It is a road movie where the landscape becomes a mirror of the soul, and the car that transports them is a protective shell in which a semblance of family is painstakingly recreated.

After tracing her whereabouts, the two travel to Houston, Texas, to find that the woman works in a Peep Show, displaying her body to invisible voyeurs behind a mirror. This revelation is a gut punch, a crude exposure of human disillusionment and solitude. The "Spyglass," the venue where Jane works, is a non-place that amplifies the theme of distance and incommunicability.

That mirror will be the barrier separating Travis from Jane, but it will not prevent them from communicating. And it is here that the film reaches its cathartic apex and its maximum emotional power. The mirror scene is a masterpiece of cinematic dramaturgy, a duet that is both silent and speaking simultaneously. Jane does not see Travis, but his voice, filtered by the anonymity of that barrier, allows her to shed her defenses and confront her past. The mirror is not merely a reflective surface, but a liminal boundary between worlds, between fragmented identities and the desperate desire for contact. One witnesses a kind of remote psychoanalytic session, where confession becomes liberation.

From that encounter, Travis's story is finally revealed: how, in an alcoholic haze, he accidentally burned down the trailer where he lived with Jane and Hunter, then wandered the desert for four years, trying to atone for what happened and remove it from his consciousness. His drifting in the desert is not merely flight, but an act of self-imposed penance, a mute and wild atonement. Travis's story is a narrative of fall and the search for redemption, a universal tale of loss and rebirth that echoes the great American myths of frontier and failure.

Travis provides the address of the hotel where Hunter is resting, but he does not want to cross that fragile crystal surface; he does not want to meet Jane. He resumes his mournful pilgrimage, leaving mother and son reunited behind him. His final choice, seemingly cruel, is in fact an act of extreme love and sacrifice. Travis does not believe he deserves happiness, or perhaps he understands that his presence, however desired, would risk destroying the newly found balance again. He is a tragic hero who accepts his condemnation to wandering, choosing solitude to ensure the happiness of others.

A film that, thanks also to Ry Cooder's crystal-clear guitar, imparts a unique charm, like a dream that persists in memory, leaving indecipherable atmospheres on the palate that unlock dormant memories and sensations. Cooder's soundtrack is not a mere accompaniment, but an essential component of the narrative, a blues lament that merges with the desert landscape, evoking America's deepest soul, that of solitary ballads and endless skies. The guitar's slide notes seem like the very breath of the desert, a backdrop of melancholy and hope that elevates the film to an almost transcendental experience.

As Wenders himself noted, this is the first film in which the plot prevails over exploration and experimentation. It is not an abandonment of his aesthetic, but rather a maturation, a sublimation of form in service of the purest emotion. The obsession with travel and dislocation, typical of Wenders' cinema, is here embodied in a human story of such intensity that formal experimentation becomes invisible, integrated into the fabric of the narrative.

The emotional vivisection that Wenders performs on Travis, stripping bare his self, is the most moving event in Paris, Texas. The German director, with his surgical delicacy, delves into the folds of the protagonist's soul, revealing the deepest wounds with rare sensitivity. It is an operation of introspection that cinema rarely manages to achieve with such power and respect.

When Travis meets Jane and, through a mirror, finds the courage to speak to her, it is great cinema, nothing more. It is the triumph of communication over alienation, of love over despair, a moment of pure catharsis that remains imprinted in the viewer's mind for its unmistakable emotional truth. A scene destined to become an icon, a perfect synthesis of a work that managed to capture the very essence of existence, between loss, search, and the arduous path towards redemption.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...