Peeping Tom

1960

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

This brilliant and controversial film by Michael Powell did not fail to suffer the barbs of censorship and of a certain part of the critics who did not forgive its subject's truculence. The reaction was, to put it mildly, catastrophic: the British press branded it as "repugnant," "sick," "perverse," going so far as to predict the end of its director's career. Indeed, his subsequent work was a children's film, almost as if to wash away the shame of that audacious dive into the murkier waters of the human soul. Yet, precisely this ferocity of initial judgment, almost a media lynching, has over time become the litmus test of its radicalism and its ineluctable modernity, a film maudit that knew how to wait for its time to be fully understood and rehabilitated, not least thanks to the ardor of exceptional cinephiles like Martin Scorsese, who recognized its far-sighted audacity.

Yet Powell, with the help of an excellent Leo Marks on script duty – a man with an enigmatic past in the secret services and a perverse sensitivity to human psychology that shines through every line – built something truly new by delving into the most remote regions of human madness to draw a lucid account from it that never fails to fascinate. Marks' writing, incisive and almost clinical, is a scalpel that dissects dark impulses, while Powell translates it into images of dazzling beauty and morbid precision. It is not a horror film in the conventional sense, nor a simple psychological thriller; it is rather a meta-cinematographic exploration of scopophilia, of the perversion inherent in the act of watching, and of the almost supernatural power of the lens, capable of capturing not only reality but also the very essence of fear and death.

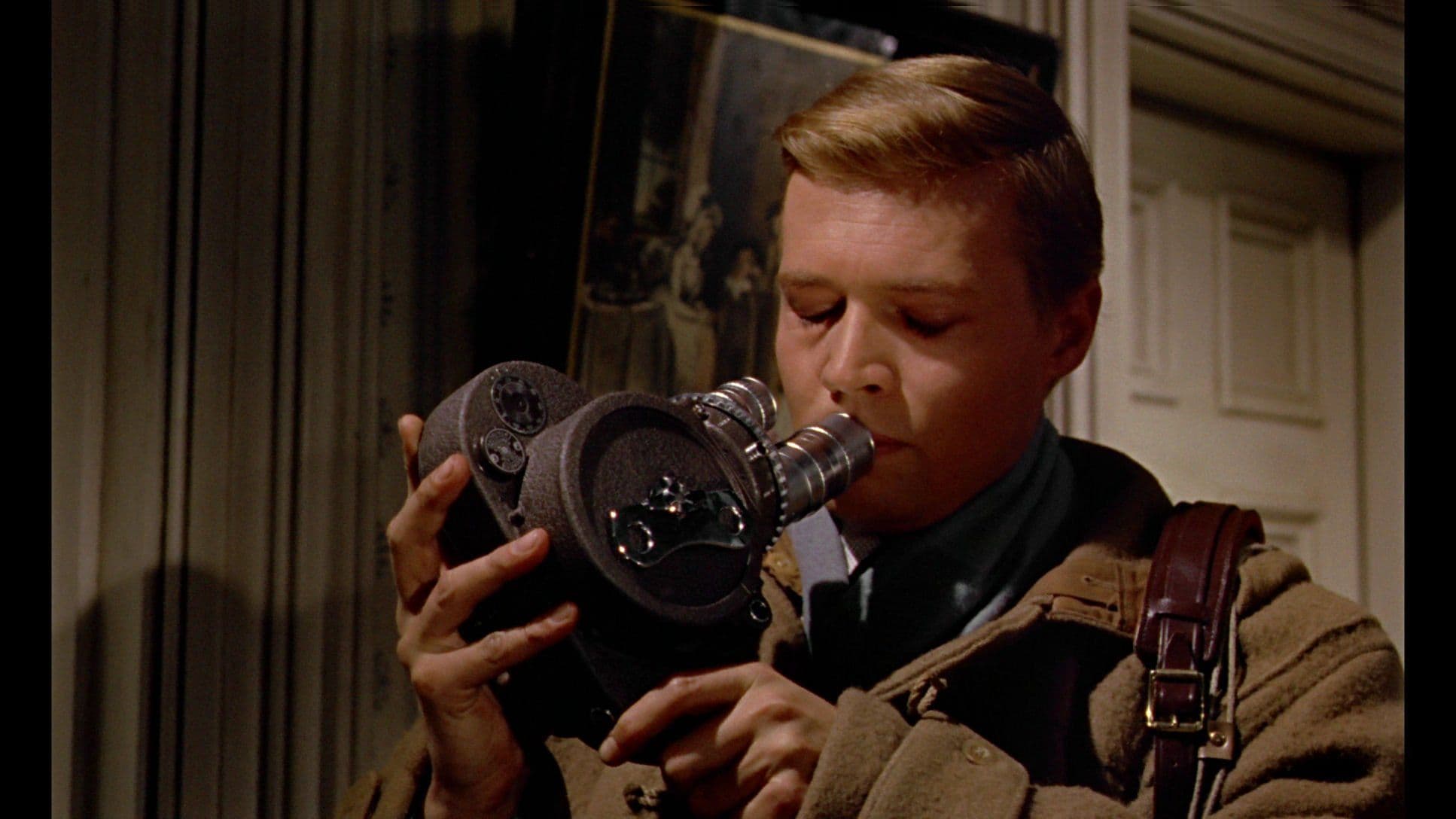

The emblematic character is Mark Lewis, a shy and awkward cinematographer, who decides to film death in the eyes of people who know they are about to die. But Mark is not a mere maniac; he is the unsettling product of a traumatic childhood, marked by the perverse and inhuman experiment of his father, a celebrated scientist who filmed him incessantly to study his reactions to fear. The film suggests, with unsettling effectiveness, that Mark's obsession with the death of others is merely the replication of a trauma suffered, a distorted form of self-therapy or, worse, the only way he knows to relate to the world and to his own, unexpressed terror. The camera thus becomes an extension of the paternal arm, an eye that not only records but also punishes, a prosthesis of his fragmented psyche.

To do this, he transforms his camera into a strange deadly device, equipping it with a bayonet with which he kills and films his victims. This "device" is not just a tool of death, but the focal point of a chilling analysis of the ontology of the image. Mark doesn't just want to kill; he wants to record death, to capture the supreme instant of loss of control, to fix forever on film the last spasm of terror. This act is a disturbing commentary on the voyeuristic nature of cinema itself, on our own complicity in watching, in consuming violent images. In a sense, Mark Lewis is the most brutal film critic, forcing his audience (and himself) to confront the rawness of existence.

In parallel, the man continues to lead a more than normal life, characterized by psychological submission and social autism. This dichotomy is crucial for his complex characterization. By day, Mark is the introverted camera assistant at Shepperton Studios, a solitary soul who finds a faint glimmer of human connection only in his neighbor, Helen, and in his almost Oedipal relationship with a blind mother, unaware of his monstrous nights. His pathology lurks in the banality of everyday life, an invisible monster walking among us, making the film even more unsettling. Powell shows us not only the dark but also the pathetic side of madness, portraying a Mark Lewis who is both executioner and victim of his own condition, trapped in a cycle of repetition compulsion, unable to break the chains of an inhuman upbringing.

The opening scene is memorable: a man silently approaches a prostitute admiring a shop window, hides a camera under his coat, the woman signals him to follow, the view shifts to subjective perspective, and the camera's eye follows the woman home, zooming in to frame her terrified face when she realizes she is trapped. This sequence is not only a stroke of directorial genius, but a programmatic manifesto. From the very first moments, Powell immerses us in Mark's distorted perspective, transforming us viewers into voyeuristic accomplices. The camera, initially hidden, becomes the killer's eye, and our eye as viewers merges with his. It is a radical subversion of point of view, foreshadowing and surpassing in audacity many future slashers, questioning the audience's passivity in the face of on-screen violence. The transition from third-person to first-person, from an external gaze to a subjective one, is an almost visceral immersion into the abyss of Mark's mind, a device that not only generates terror but forces us to reflect on our own morbid curiosity.

A splendid spin-off of a genre balancing between horror and psychological thriller, an almost unexplored vein that Powell had the merit of traversing with the immense professionalism that distinguished him, crafting a work with truly noteworthy ideas and insights. Released in the same year as another masterpiece of psychological terror, Hitchcock's Psycho, "Peeping Tom" stands out for its stylistic and thematic audacity, pushing where Hitchcock stopped at the threshold. If Norman Bates is a monster hiding behind normality, Mark Lewis is normality itself revealing itself as monstrous in the act of watching and recording. Powell's film does not merely frighten; it destabilizes, questions the role of the cinematographic medium, our thirst for images, and the subtle line separating observation from complicity. It is a work that was ahead of its time, influencing generations of filmmakers, from the directors of Italian Giallo to those of New Horror, and continues to resonate powerfully today, in an era where the reproduction and circulation of images has become omnipresent and pervasive, making its reflection on the voyeuristic power of the camera more relevant than ever. An authentic, unsettling masterpiece.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...