Dog Day Afternoon

1975

Rate this movie

Average: 4.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Lumet, always interested in circumnavigating the media sphere and its sociological implications, pushes his analysis into true crime and, starting from a newspaper article, constructs a frantic work with a perfectly crafted narrative. His acute ability to dissect institutions and power dynamics, already evident in masterpieces like Serpico or Network, finds a new and disturbing manifestation here, anchored in an almost documentary realism that draws directly from the rawest current events. The director, with his refined sense of drama and tension, inherited from his long experience in theater and live television, orchestrates every single frame with surgical precision.

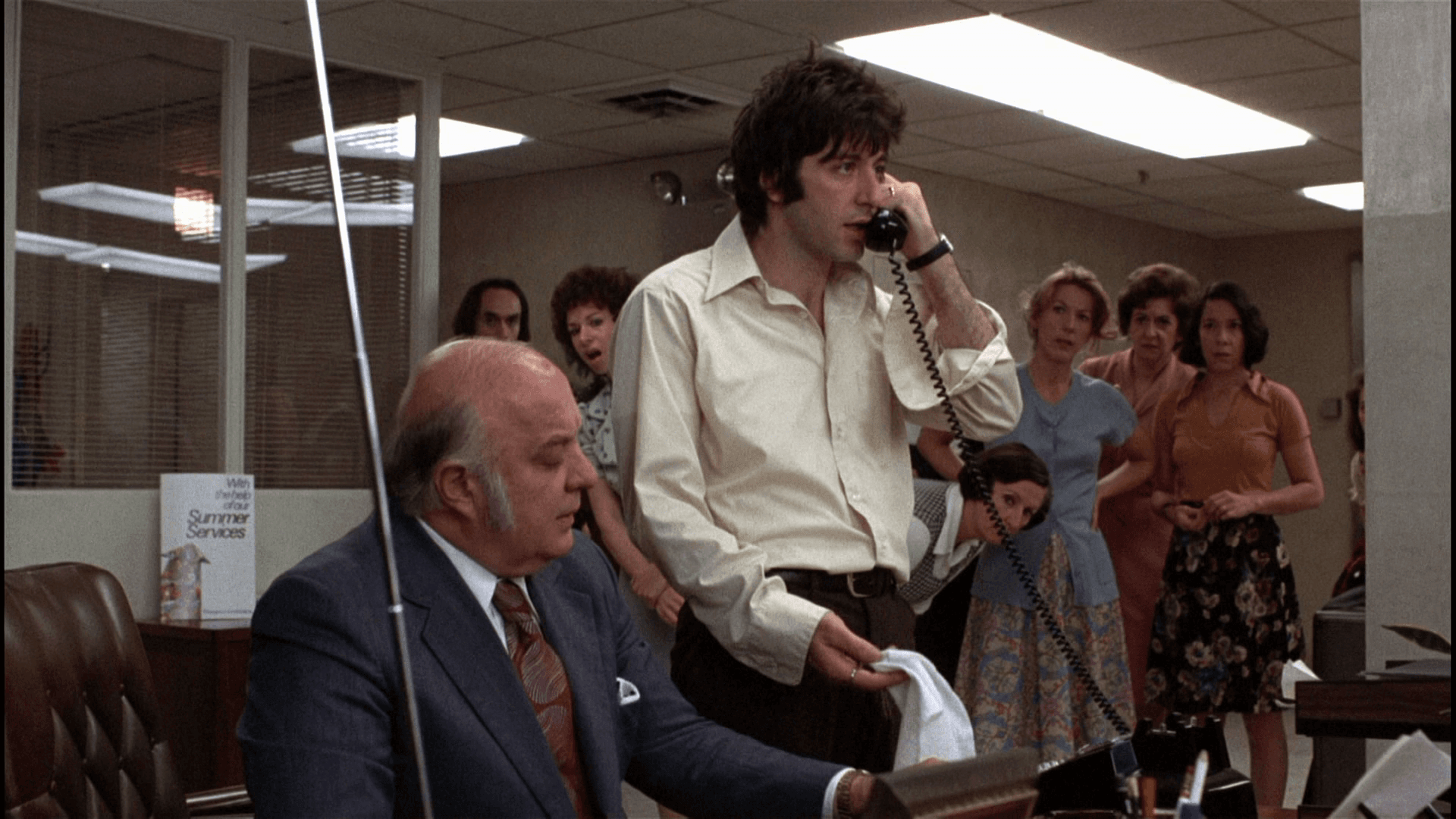

The story is entirely based on a bank robbery gone wrong, with the robbers, besieged by the police, taking the branch employees hostage and barricading themselves inside the building. What should be a simple criminal operation transforms into a surreal siege, an involuntary performance unfolding under the eyes of a tumultuous New York, itself a metaphor for an America poised between post-Vietnam disillusionment and the incipient cynicism of the Watergate era.

Gradually, the event will be chewed up by the big media machine, transforming it into a surreal sarabande of hypocrisy. Lumet does not merely observe, but mercilessly dissects the birth of the media circus, a phenomenon that was powerfully taking hold in the 1970s and which the director had already prefigured with his merciless satire in Network, albeit with a more markedly farcical tone. Here, personal tragedy and the news event are cannibalized, transformed into voyeuristic entertainment for the thronging crowd and for millions of tuned-in viewers, eager to consume others' drama as if it were the latest episode of a soap opera. The public, initially curious, transforms into a shrill and fickle Greek chorus, cheering or booing based on the mood of the moment, in an exemplary demonstration of the fragile boundary between information and spectacle.

Interesting is the experiment of pivoting the narrative fabric on a single setting with a strong theatrical flavor. The bank becomes a cramped and claustrophobic stage, where the characters are forced to play their roles in a contemporary commedia dell'arte, under the spotlights of helicopters and cameras. This device, reminiscent of his illustrious 12 Angry Men, allows Lumet to focus attention not so much on external action as on the characters' psychology and their interactions. The physical siege translates into a psychological siege, in which every exchange, every line, acquires an unprecedented specific weight.

Once it becomes clear that the two robbers cannot escape, a microcosm is created that is all Lumet needs to tell his story: the interrelationships between bandits and hostages, the difficult relationships with the outside world, the escalating tension: everything is confined within a small nest. Here, complex dynamics unfold: from the Stockholm Syndrome that begins to veil the relationship between Sonny and his "prisoners," to subtle power plays and unexpected solidarities. The bank, from a place of economic transactions, transforms into a crossroads of human destinies, a social laboratory where masks fall and true personalities emerge under unbearable pressure. The film thus transforms from a simple "crime movie" into an acute and layered analysis of society, its neuroses, and its extreme reactions.

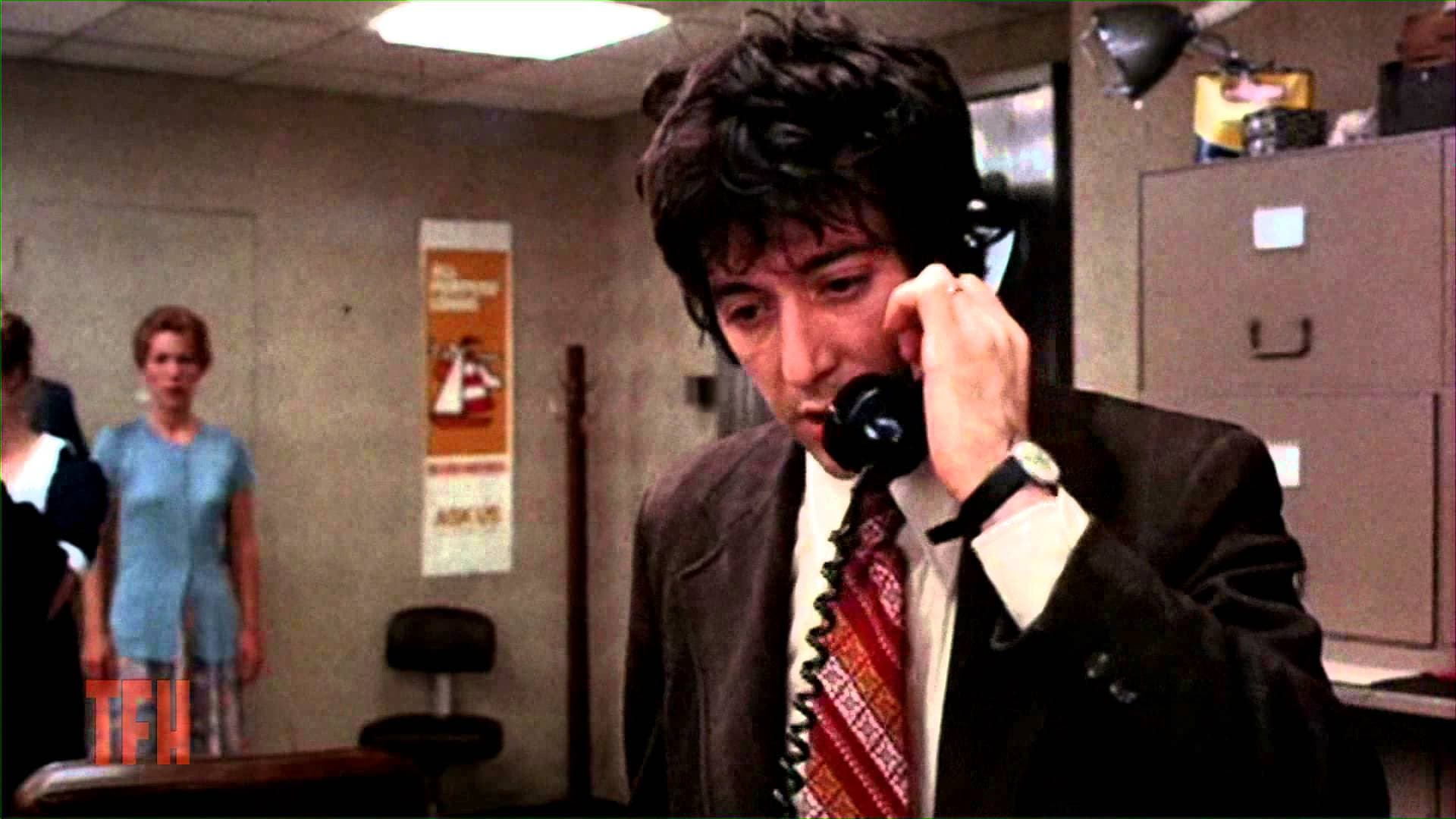

The initial sequence of the robbery is wonderful, when an awkward Sonny pulls his rifle from a package and gathers all the employees against the wall while one of the three robbers has a breakdown and abandons them in the middle of the robbery. What should be a tense and threatening opening scene immediately proves to be clumsy, embarrassing, tinged with a dark humor that anticipates the chaos and absurdity that will follow. It is a stroke of narrative genius that immediately disarms genre expectations, presenting the protagonists not as tough criminals, but as pathetic amateurs, almost tragic clowns. Al Pacino's expression of bewilderment at that moment is a compendium of vulnerability and despair, immediately immersing us in the fragmented psychology of his character.

Pacino's masterful work in sculpting the protagonist completes the rest of the film and makes it an indispensable cornerstone in the crime movie genre, tightly intertwining it with the critique of media overreach. His portrayal of Sonny Wortzik is a gem of intensity and complexity: a desperate, vulnerable man, at times comical and at times enraged, whose motivations are, surprisingly, sentimental and even progressive for the era (raising funds for his partner's gender reassignment surgery). Pacino, at the peak of his 1970s career, delivers a layered character, an anti-hero who evokes both pity and a bizarre admiration, transforming from an improvised robber into an improbable folk hero, acclaimed by the crowd chanting his name. It is precisely thanks to Sonny that the film transcends mere genre, transforming into a keen examination of identity crisis, the disillusionment of the American dream, and the search for acceptance in a world that seems incapable of embracing diversity. His is a cry of pain and defiance that still resonates today with disturbing force.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...