Ran

1985

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Kurosawa’s Ran, a Shakespearean reinterpretation of King Lear, immediately took on the hallmarks of a seminal work. It is not a mere transposition, but a radical reinterpretation, steeped in a nihilism that distinctly sets it apart from the Elizabethan original. Kurosawa, while acknowledging Shakespeare’s genius, pushes the themes of tragedy beyond the point of no return, stripping humanity of any hope or divine intervention, leaving it alone with the consequences of its own atrocities. Ran stands as the director’s last, majestic epic, a definitive testament to his grand and disenchanted vision of history and human nature.

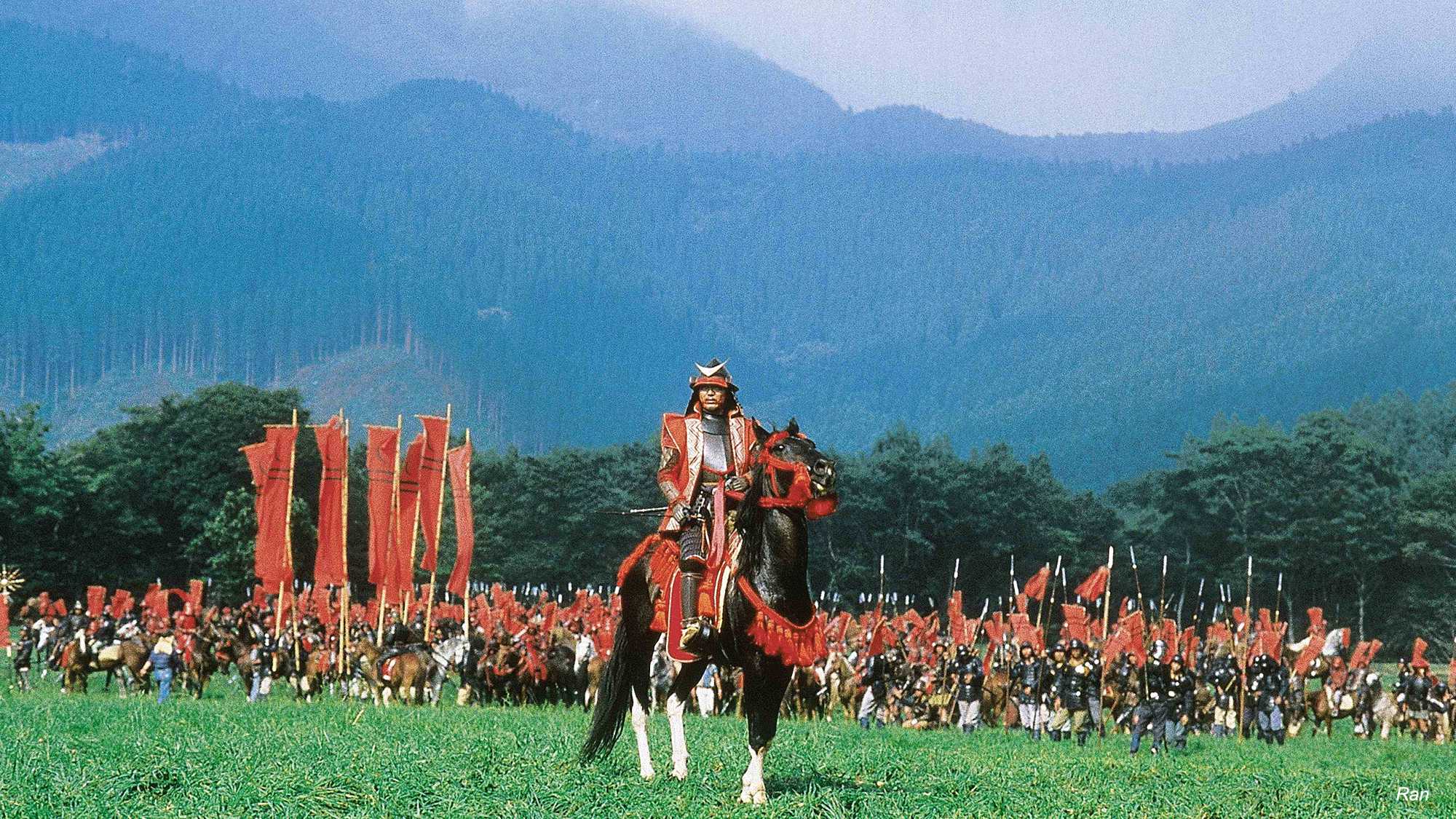

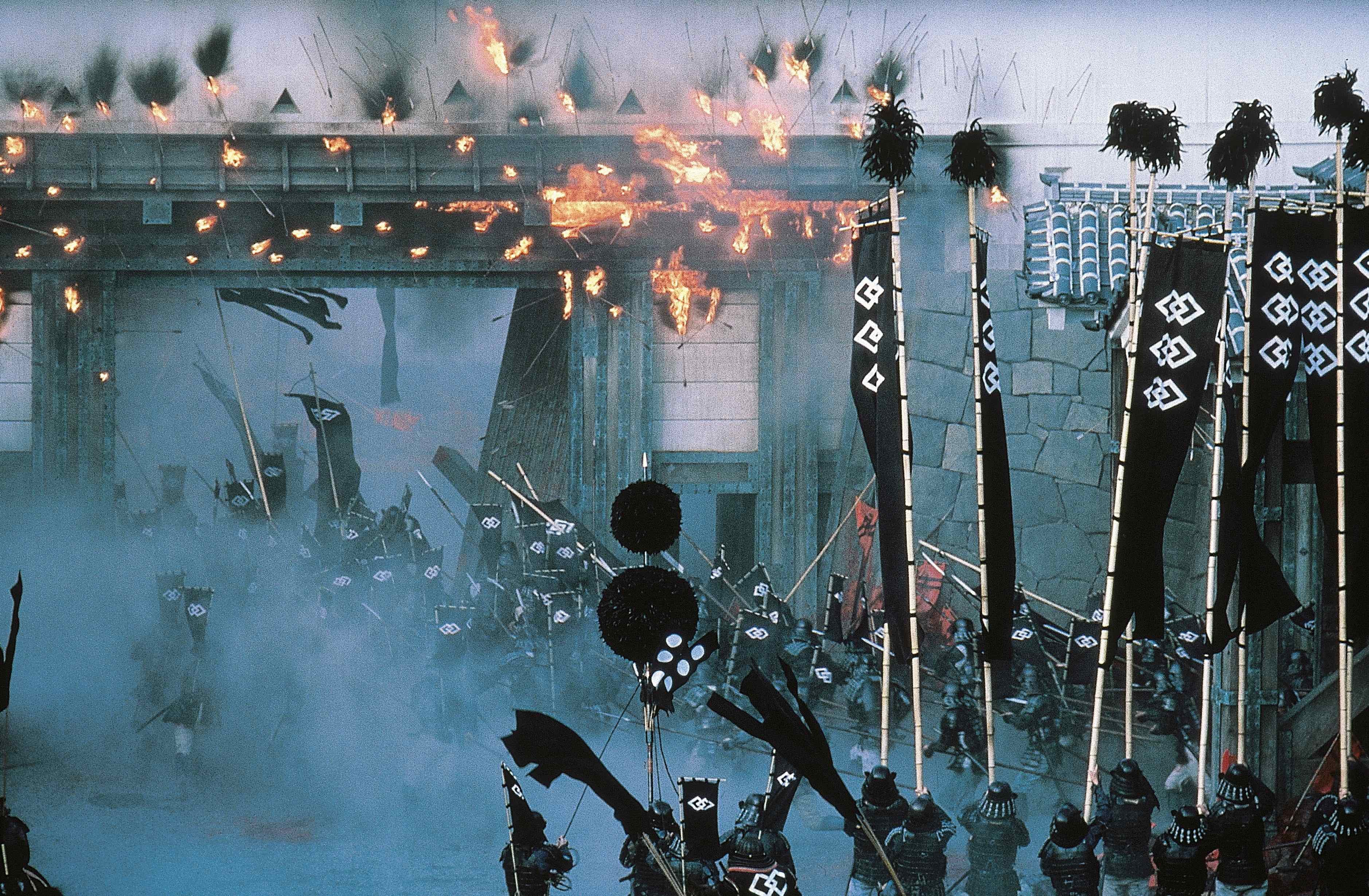

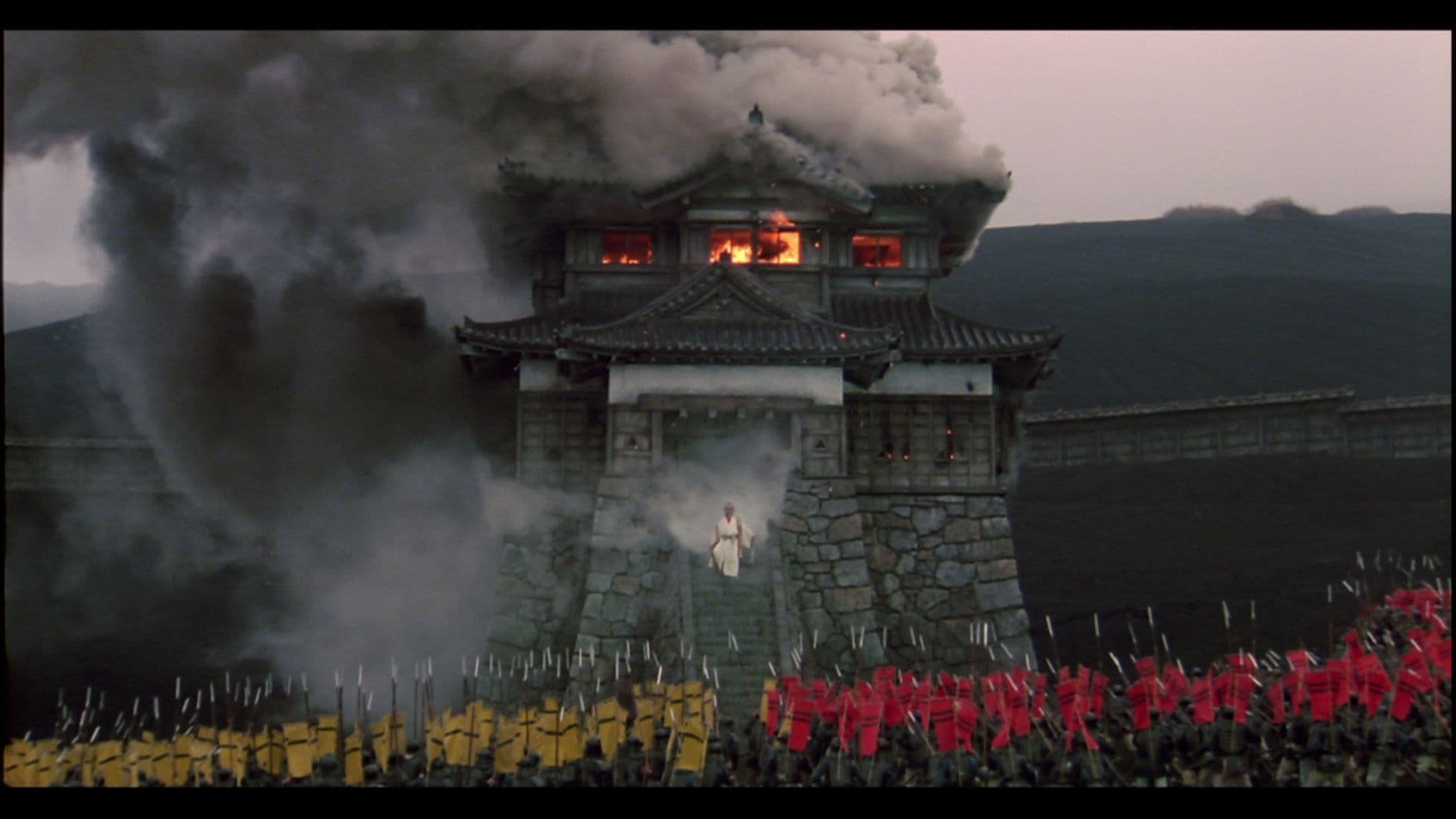

First and foremost, it is a majestic work involving thousands of extras, costumes, filming locations, historical reconstructions, years of shooting, and post-production work for nearly three hours of running time. This titanic ambition is not merely a stylistic flourish, but the beating heart of the narrative, an element that bestows an almost operatic gravitas upon the drama. It is said that Kurosawa dedicated a decade to pre-production alone, hand-painting every single storyboard like actual paintings, an obsessive meticulousness that testifies to the director’s absolute vision and artistic intransigence. The battles, though orchestrated on an epic scale with hundreds of horses and thousands of samurai, retain a tangible rawness, devoid of the aseptic stylization typical of modern digital productions. Every collision, every arrow whistling through the air, resonates with a physical weight and a painful veracity that only the use of real means, mastery in mass choreography, and the choice to often film in long shots can confer, making Ran a monument to handcrafted cinematic art, a logistical and creative undertaking almost unthinkable today.

Kurosawa is said to reinterpret Shakespeare, but he does so by accentuating the tones of madness and cruelty in every character involved. Where Shakespearean Lear might find a kind of catharsis in his madness and a glimmer of redemption in his bond with Cordelia, Kurosawa’s Hidetora is condemned to an agony with no escape, wandering in a desert of ruins he himself created. His madness is not merely mental derangement, but the naked exposure of a soul stripped of all illusion, forced to confront its own hubris and the inexorable, blind decline of an order. It is a madness that leads not to wisdom, but only to a deeper and more painful awareness of chaos.

All the events in Ran are haunted by violent passions that culminate in titanic conflicts. It is a drama where dignity and honor, pillars of the samurai code, give way to an atavistic thirst for power, an escalation of violence and betrayal that offers no escape. The film portrays humanity corrupted by its own greed, destined for cyclical and inevitable self-destruction, a recurring theme in Kurosawa’s work (e.g., Throne of Blood), which here reaches its apogee of despair and fatalism.

Ran, which in Japanese has the ambivalent meaning of chaos and madness, is set in 16th-century feudal Japan. This period, known as Sengoku Jidai (the era of warring states), was an age of political instability and incessant conflict, fertile ground for the most atrocious manifestations of human nature. The title itself is a key to interpretation and not merely a plot summary: it is not just about civil war, but the disintegration of every structure, moral and social, an entropy that engulfs everything, from family relationships to the integrity of the realm, perfectly mirroring the inherent anarchy of the historical period.

A local warlord, on the verge of death, divides his domain among his three ambitious sons. However, the division of the domain unleashes a fratricidal war that will escalate into a bloody civil war. Old Hidetora, blinded by his own desire for rest and by his past tyranny – having himself seized power with extreme violence – fails to discern the true loyalty of his youngest son, Saburo, and underestimates the treachery of the other two, Taro and Jiro, unleashing a chain reaction of vengeance and betrayals he can no longer control.

Memorable then is the Lord’s condemnation of base passions culminating in the lust for power, a monologue imbued with a bitterness and cynicism from which there is no escape. His descent into madness is a visual and psychological epic: we see him wander, mute and distraught, amidst the smoldering remains of his ambitions and his burned fortresses, a king stripped of everything but his despair. The images of Hidetora, once a powerful warlord, now merely an empty shell in a desolate world, remain imprinted for their desolate beauty, almost as if they were scenes from an ancient Greek tragedy set amidst the ruins of a mad world.

Among the many scenes, one resurfaces with particular persistence: Kurogane, an officer in Jiro's army, confronts Lady Kaede, Jiro's lover, who has driven him to ruinous war by manipulating him at will. He demands an explanation from the woman for the downfall of the house and receives a scornful reply: “it was precisely my intention to bring down Jiro's house to avenge my father's death.” The woman utters the phrase, looking at the soldier with contempt and defiance. Lady Kaede is not simply a vengeful figure or a manipulator; she is the embodiment of an ancestral fury, an elemental force that, like war itself, knows neither pity nor human logic, driven by an implacable thirst for justice for the wrongs suffered by her family. Her glacial beauty conceals a keen mind and a heart of stone, making her one of the most memorable and disturbing antagonists not only in Kurosawa’s cinema but in the entire history of film. Her violent and sudden death is an almost ritualistic act of purification and, at the same time, a seal on the ineluctable fate of the Hidetora dynasty. Kurogane then lowers his katana onto her snowy neck, streaking the room’s wall with scarlet, but Kaede’s vengeance is now complete. The echo of that cut, the contrast between the whiteness of the skin and the red blood, is an image of pure pictorial art, a visual haiku of brutality and fatalism, a moment of chilling stasis in the maelstrom of madness.

A film dense with somber events, cruel figures, and epic narration interspersed with refined psychological investigation that enriches every single frame. Kurosawa does not merely tell a story, but constructs a visual and auditory universe of rare power, using color with almost symphonic precision and stratified symbolism: the gold of the main house, Jiro’s fiery red, Taro’s icy blue, Saburo’s vibrant yellow. These vibrant hues are not just military insignia, but symbols of the primary forces in conflict, clashing in a tapestry of impressive violence and baroque beauty. His direction, which alternates extreme long shots that annihilate the human figure with close-ups of inner desolation and deafening silences (as in the battle sequences devoid of music, dominated only by wind and the clang of steel), transforms the Shakespearean drama into a universal meditation on the futility of war, the fragility of power, and the inexorable cycle of violence. Ran is not just a film, but a cathartic experience, a work that transcends time and cultures to question the very essence of human nature, leaving the viewer with a sense of admiration and an unsettling awareness of our intrinsic, tragic madness. It is a timeless masterpiece, the culmination of the genius of a director who managed to fuse Eastern epic with Western tragedy into an unsurpassed unicum, destined to resonate for generations.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...