Salvatore Giuliano

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

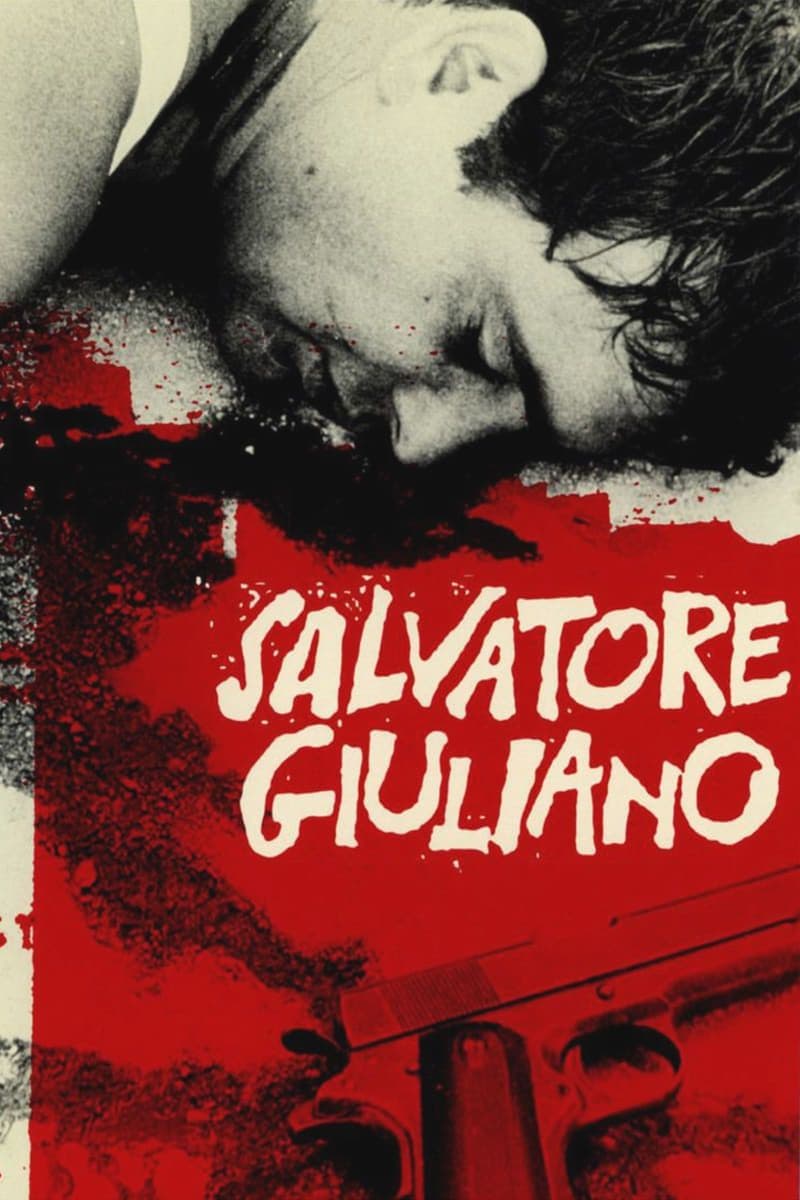

A body lies like a horrid trophy in a courtyard in Castelvetrano, province of Trapani, while the anaffective voice of an official describes its squalid details with taxonomic precision. This disarming opening, almost an incipit from a medico-legal report, immediately sets the disenchanted and implacable tone of Francesco Rosi's work. There is no romanticism, no pity, only the raw exposition of a truth that purports to be objective, but which will reveal itself to be layered and multifaceted, much like a forensic investigation into the mysteries of a nation.

Covered in blood, his proud face is discernible; it belongs to a man who populated the imagination of every Sicilian for over thirty years: the bandit Salvatore Giuliano. The image, powerful in its static violence, evokes an almost mythological iconography of the "King of Montelepre," but Rosi is here to deconstruct it, to expose violence as a symptom of a deeper evil, not as a mere individual manifestation. Giuliano, far from being the "Robin Hood" of Sicily or the romantic hero depicted by certain popular narratives, becomes, under the director's keen gaze, the crossroads of occult powers, of interests that far exceed his own, albeit bloody, epic. The film is not so much about Giuliano the man, as it is about Giuliano the catalyst, the pretext for unveiling a greater, more uncomfortable truth.

Thus begins this extraordinary film by Rosi, perhaps the culmination of his art and his directorial trajectory. And indeed, it is here that Francesco Rosi's cinema, in a black and white of dazzling photographic precision that recalls both documentary rigor and the stark beauty of the best neorealism, achieves unmatched formal and thematic maturity. If neorealism had taught us to look at reality with an unadorned and empathetic eye, Rosi reclaims its legacy to transcend it, transforming chronicle into "investigation," narrative into a social and political anatomy. Salvatore Giuliano is not just a film about the Mafia or banditry; it is a meticulous investigation into the nature of power, its ability to corrupt, manipulate, and ultimately annihilate anyone who stands in its path, be it a bandit or an innocent farmer.

Through flashbacks, the bandit's life is reconstructed, closely overlaid with the life of Sicily from the 1930s to the 1950s: the Mafia's relationship with institutional power, state repression of the weakest, the connivances and contradictions of a magnificent land infested with undignified parasites. The narrative structure, fragmented and non-linear, proves to be a stroke of genius, reflecting the elusive and manipulated nature of "truth" in a context where reticence and omertà are law. Rosi does not present us with a linear biography, but a mosaic of events, testimonies, and backstories that interlock to paint a dark and disenchanted fresco of post-war Sicily. The editing, tense and relentless, guides the viewer through the meandering paths of an island where the wild beauty of the countryside and mountains serves as a backdrop to endemic, almost geological violence. The landscape itself becomes a silent character, accomplice and spectator of centuries-old tragedies, whose aridity is not only physical but moral. This "magnificent land infested with undignified parasites" is a diseased living organism, and Giuliano's banditry is merely one of its most conspicuous symptoms, not the ultimate cause. Rosi reveals how the Mafia, far from being a parallel organization, is woven into the very fabric of the state, an "anti-state" that feeds on its weaknesses and collusions, a theme that Italian cinema would later explore in depth with directors like Elio Petri or Damiano Damiani.

Memorable are the scenes of the bloody massacre of peasants at Portella della Ginestra, on May Day of forty-seven, an indelible stain on Italian history. The dramatic, and perhaps moral, climax of the film is undoubtedly the reconstruction of this massacre. Rosi does not merely show us the carnage; he makes us feel the despair, the terror of those peasants celebrating May Day, their naive trust in a future of social redemption, brutally shattered by lead. The sequence is shot with breathtaking visual and sonic power: the echo of gunshots fading into the wind, bodies falling, the chilling silence that follows the fury. It is a moment of pure cinema, of documentary force that elevates the tragedy to a universal warning, a warning about the fragility of democracy and the persistence of dark powers capable of sacrificing innocent lives on the altar of their interests. Rosi's skill lies in making the horror palpable without ever resorting to sensationalism, maintaining that critical distance which is the stylistic hallmark of the entire work.

Rosi never expresses moral judgments; his is a cold work of documentation, almost a chronicler hidden in the folds of history who reports the facts to us in their ruthless rawness. This stylistic choice, that of a "hidden chronicler," is what distinguishes Rosi from many other directors who have tackled social or historical themes. There is no didacticism, no preconceived thesis, other than to expose the complexity of facts and their interconnections. It is an approach that anticipates and defines Italian "civil cinema," of which Rosi would become the undisputed master, influencing generations of filmmakers. Consider films like Hands Over the City or Illustrious Corpses, where the same implacable investigative logic dismantles the mechanisms of corrupt power. Rosi does not judge, but shows; does not condemn, but reveals. He leaves it to the viewer to draw their own conclusions, to confront an uncomfortable reality that has too often been sweetened or mystified. For this reason, Salvatore Giuliano is not just a historical film, but a visual essay, a work of applied political philosophy, which investigates collective and individual responsibilities in a chain of fatal events. His "coldness" is in reality a searing lucidity. The performances of the actors, many of whom were non-professionals recruited on site, such as the imposing Frank Wolff in the role of Carabinieri agent Gaspare Pisciotta (who acts with impressive naturalness), or professionals of Salvo Randone's caliber, contribute to this almost documentary authenticity, blurring the line between fiction and reality and reinforcing the illusion of being faced with an authentic journalistic investigation.

A film that violently shakes consciences and remains one of the highest points of Italian cinema. Sixty years after its release, the work maintains its shocking power intact, revealing layer upon layer of uncomfortable and interconnected truths. It is a cinematic monument that does not age, a beacon that continues to illuminate the shadows of a country that still struggles to come to terms with its past and with persistent power dynamics. In a cinematic landscape often prone to easy storytelling or spectacularization, Salvatore Giuliano stands as a bulwark of critical intelligence, moral rigor, and aesthetic inquiry. It is a masterpiece that does not merely narrate a story, but invites reflection, methodical doubt, and the unveiling of those hidden truths that underpin every exercise of power. An indispensable film, not only for those studying Italian history or cinema, but for anyone seeking in the big screen a mirror capable of reflecting, without filters, the complex and often painful human condition.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...