A Matter of Life and Death

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

The award-winning team Powell Pressburger strikes again. And they do so in the most original way with a groundbreaking work that breaks from the pre-packaged cliché of postwar Hollywood, an audacious foray into the fantastic that transcends genre boundaries to touch the deepest chords of human experience. Stairway to Heaven – or, in its more evocative original title, A Matter of Life and Death – is not simply a film, but a true cinematic manifesto, a sublime demonstration of the genius of directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, whose artistic union, known as "The Archers", redefined British cinema with a bold, often psychedelic, and always profoundly humanistic vision.

English airman Peter Carter, returning from a bombing mission, is hit by anti-aircraft fire and realizes his parachute is unusable. Sending out an SOS on the radio, he has the chance to speak with June, a girl serving in the USAF, who convinces him to take a chance. Jumping from his plane, he falls into the fog and miraculously wakes up unharmed on a beach. His time should have been up, but a mix-up occurred in Heaven, and the man survived death. Now, in the Celestial Headquarters, a debate rages over whether the man should live or die, given that he has found love with June. This premise, which in itself defies all logical convention, becomes fertile ground for one of the most ingenious and touching allegories about life, death, and cosmic bureaucracy ever conceived. The film, conceived during a critical period of the Second World War and even commissioned by the British Ministry of Information to improve Anglo-American relations, transcends its initial propaganda purpose to transform into a universal ode to love and the resilience of the human spirit. The Peter-June dichotomy, in fact, becomes the vehicle not only for a compelling romance but also for a witty and slightly ironic exploration of the cultural differences between the two nations, playfully celebrated and staged in the phantasmagorical celestial court.

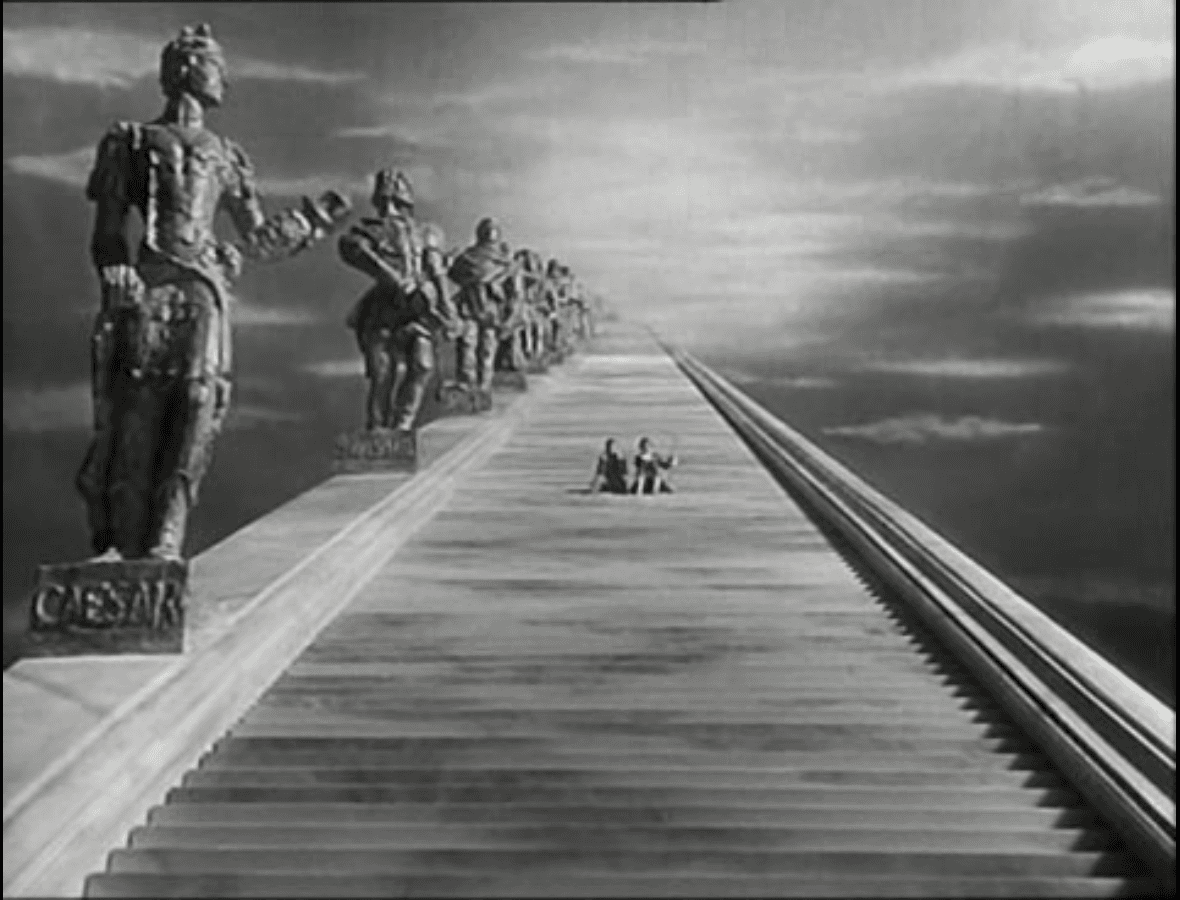

It is precisely in this otherworldly context that Powell and Pressburger reveal their mastery, pushing the technical and expressive possibilities of the cinematic medium to previously unexplored limits for the era. Thanks to astonishing technical innovations – the filming of the assembly of souls is extraordinary, a kaleidoscope of eras and characters, from ancient warriors to extinct poets, all united in a single, surprising post-mortem community – and a pulsating screenplay, the filmmaking duo delivers to history a new way of making cinema. Their lesson remains undiminished in its freshness to this day, precisely for its ability to merge the sublime with the everyday, the fantastic with the profoundly human. The transition from the flamboyant Technicolor of Earth to the severe and stylized monochrome of Heaven is not merely a visual virtuosity, but a witty reflection on the nature of perception and reality: earthly life, with its imperfection and chaos, is rich in colors and passions, while the afterlife, though orderly and rational, is by definition devoid of the sensory vitality that distinguishes existence. This aesthetic choice, a kind of "Wizard of Oz" in reverse, elevates the film's central philosophical debate: is what we see with our eyes more real, or what we perceive with our heart and mind?

The architecture of the "otherworld" is a triumph of design and concept: endless moving staircases, celestial waiting rooms where the deceased converse with the nonchalance of someone waiting for a train, and a tribunal where a man's life is put to a vote with irreverent formality. The judge, played by the magnificent Marius Goring, is a French doctor guillotined during the Revolution, who perfectly embodies the wit and intellect that permeate every dialogue. His brilliant cynicism and hidden humanity are the perfect counterpoint to Peter and June's pure, disarming faith in their love. The film goes beyond the simple juxtaposition of life and death, exploring the power of will, the boundary between lucidity and madness (with the brilliant figure of the surgeon Conductor 71, played by Roger Livesey, whose destiny is linked to Peter's), and the conviction that love can be a force so powerful as to alter even the course of cosmic destiny. The final sequence, with June's desperate dash towards the escalator that takes Peter away, is a moment of pure cinema that condenses the anguish of loss and indomitable hope. Stairway to Heaven is not only a masterpiece of technique and narration, but a joyous and moving hymn to life, a reminder that even in the greatest absurdity, love and human connection can find a way to prevail. A film that, decades later, continues to shine with its own eternal and unique light.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...