Se7en

1995

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A dark, bleak work whose semantic pillars are growing anguish and an oppressive sense of persecution. It is not simply a thriller, but a visceral and intellectual exploration of moral decay, a neo-noir that transcends the genre to become a philosophical commentary on the human condition in an era of apathy and despair. Fincher does not merely show us evil; he plunges us into it, making us breathe its stale, rain-saturated air.

Se7en is a film that, while falling within the typical canons of the detective film – a methodical serial killer, two police officers investigating his macabre crimes, an intrinsically symbolic death ritual – deconstructs and reinvents them with disarming ferocity and lucidity. Its strength lies not in the novelty of the premise, but rather in the brutality with which it is developed and, above all, in its relentless, almost nihilistic, conclusion. It is an ode to disillusionment, a disturbing fresco of humanity that has lost its ethical compass, and in which evil is not an aberration but an endemic plague.

What makes Se7en truly interesting, and a turning point for genre cinema, is the masterful use of cinematography, photography, and the narrative structure of a screenplay (Andrew Kevin Walker's pen was excellent, as he managed to resist pressure to soften such a radical ending), all elements subservient with rare coherence to the creation of a dark, uncertain atmosphere, permeated by a sense of dampness and urban squalor. Even the name of the city where the story is set is unknowable, a non-place that reflects a universal, non-geographical existential condition: the metropolis here is merely a container of corruption, an ecosystem of physical and moral filth.

We have spoken of the photography: a tool truly at the service of the narrative, elevated to a genuine autonomous language. Darius Khondji, the director of photography (already a collaborator of Jeunet and Caro in Delicatessen, and later a master of light for directors of the caliber of Wong Kar-Wai and Woody Allen), performs an operation of darkening and filtering the scenic light with rare intensity. Through the skillful use of techniques like bleach bypass, which desaturates colors and intensifies contrast, Khondji creates a palette of dull grays, sickly greens, and earthy browns, visually reverberating the growing sense of anguish that the film instills. It is not just an absence of light, but a corrupted, sickly light that pervades every shot, transforming even daylight into a continuation of a foggy and rainy nightmare.

Two police officers, the cynical but still idealistic veteran William Somerset (Morgan Freeman in a state of grace, an emblem of weary but unyielding wisdom) and the impulsive and idealistic young David Mills (Brad Pitt, who demonstrates a surprising ability to delve into psychological frailties), are on the trail of a serial killer who murders his victims following the path of the seven deadly sins. Each victim represents the sin they excelled in during life and is punished by being made an example, a symbol of rebirth through the purification of death. The killer's modus operandi, John Doe, is not random: it is a perverse form of preaching, a macabre sermon on the decay of a society that has lost all ethical sense, having become blind and indifferent to its own vices. His brutality is not an end in itself, but a means to awaken dormant consciences through horror, a biblical exegesis taken to its extreme and cruellest consequences.

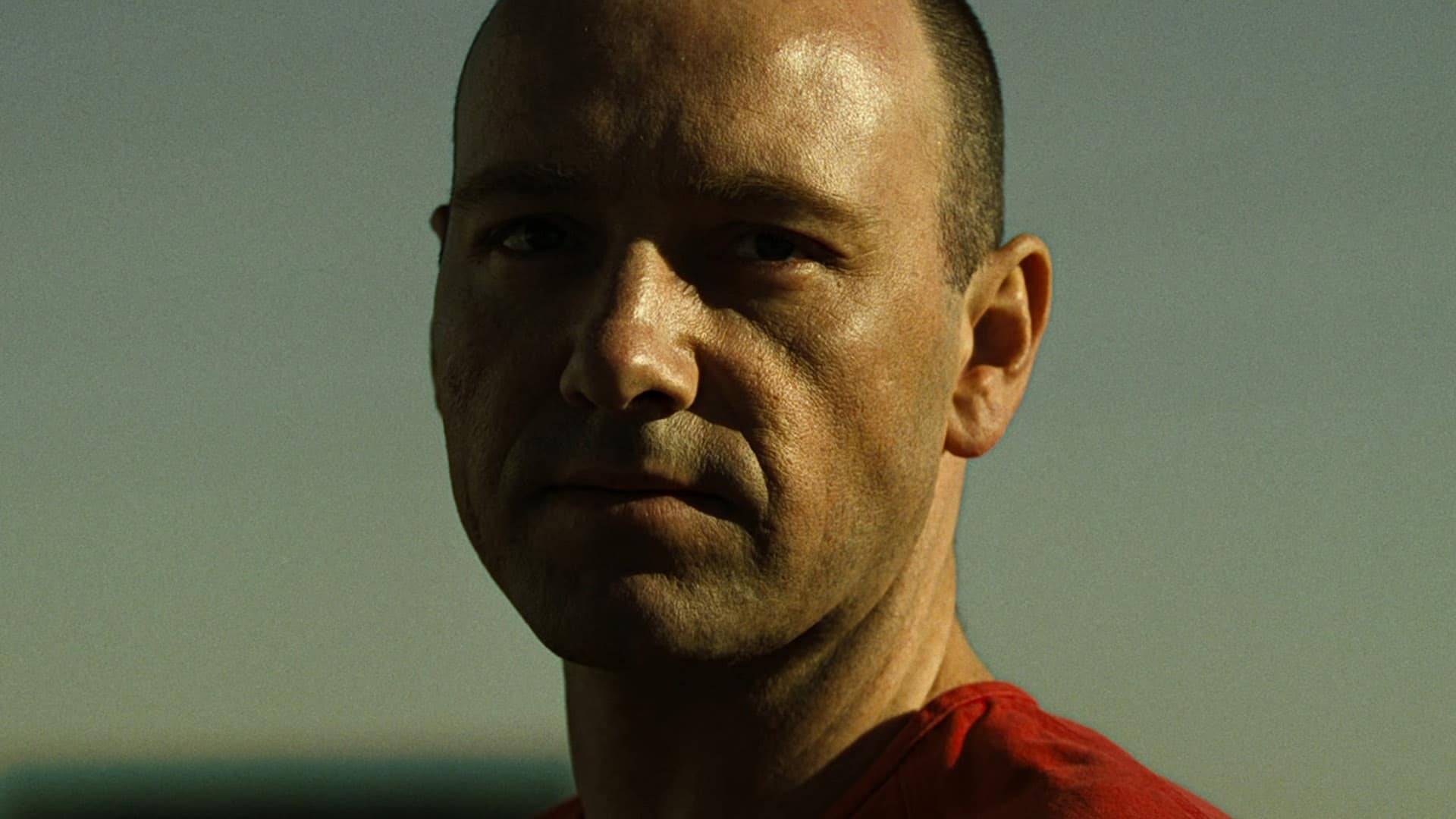

The two police officers, each holding diametrically opposed worldviews, soon realize that their investigation is also part of the killer's diabolical plan. John Doe is not a mere assassin to be caught, but an architect of destiny, a director of tragedy, who manipulates events and the lives of the protagonists with surgical precision. His glacial intelligence and his monastic dedication to his “work” elevate him above the common criminal, making him almost a force of nature, a dark prophet of a distorted divine justice. The game between hunter and prey constantly reverses, revealing an intricate web of manipulation in which Mills and Somerset are, unknowingly, the final, and perhaps most significant, pieces on Doe's mortal chessboard.

Special and due mention must be made of the final scene, a sequence that has become a cinematic icon and crystallizes the film's philosophy. In that arid and sun-drenched desert, Fincher masterfully manages the suspense and tension that grow exponentially with the unfolding of events, leading up to the plot twist that overturns all expectations. The emotional escalation is palpable, an ineluctable progression towards horror and despair, orchestrated with almost sadistic precision. The deafening silence, broken only by the wind and the distant sound of a helicopter, amplifies the emotional claustrophobia. The revelation of the box's contents, "What's in the box?!", is not just a plot twist, but the materialization of the inevitable triumph of John Doe's nihilistic vision. The ending offers neither catharsis nor redemption, but a punch to the gut that leaves the viewer with a sense of profound desolation. It is the victory of evil not as an isolated event, but as an ineluctable destiny in a world that has stopped fighting, and which demonstrates how the deepest darkness resides not in the monster, but in its ability to instantly shatter any lingering hope in order and justice.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...