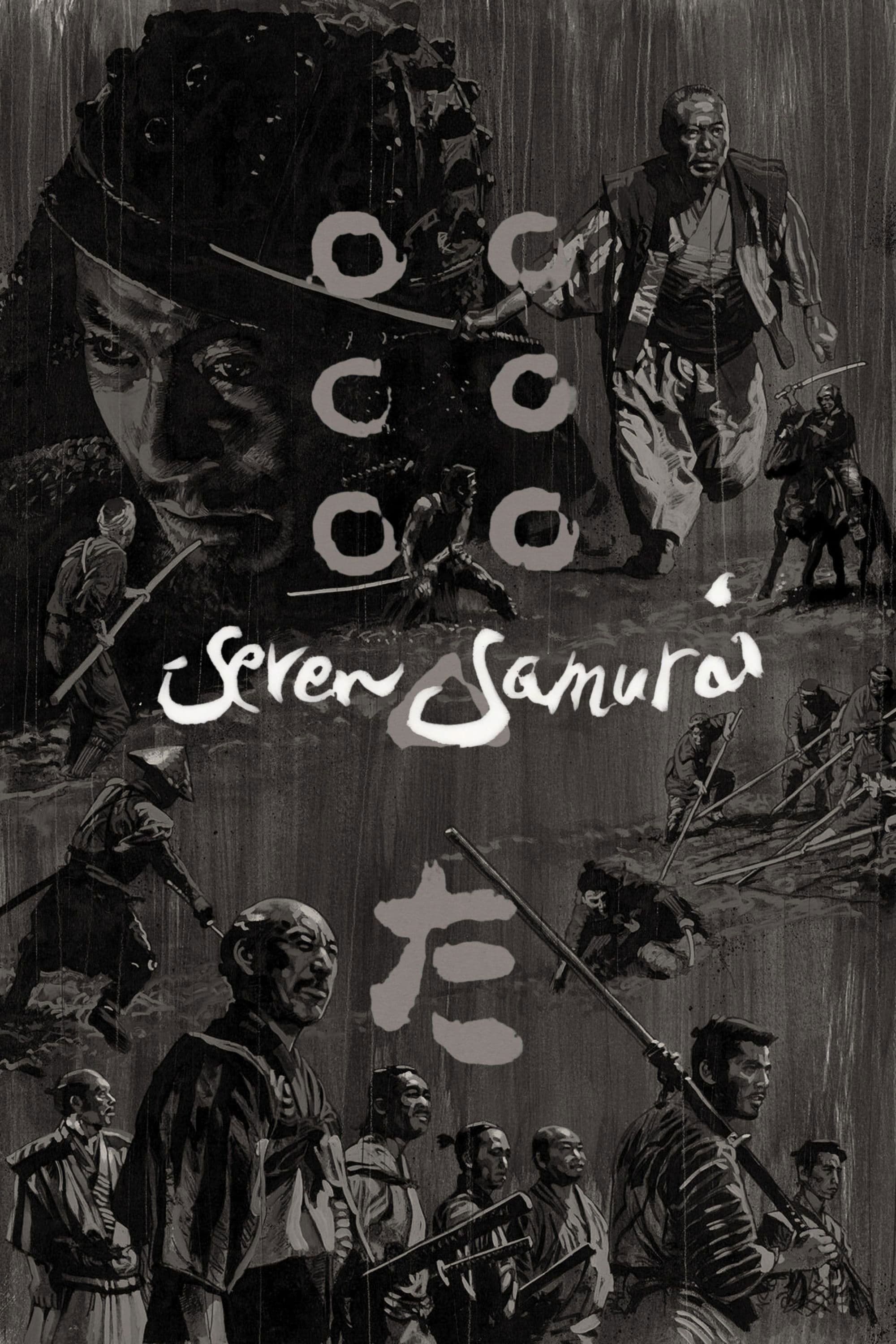

Seven Samurai

1954

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Akira Kurosawa once again sets his camera in medieval Japan, but it is a Japan of transition and ferment, the chaotic and bloody Sengoku period, to tell us the story of a handful of daring unemployed samurai who find employment with a village frequently attacked by bands of marauders. It is not mere unemployment, but the symptom of an increasingly anachronistic warrior class, the ronin, masterless samurai, whose very existence is threatened by a changing world where the loyalty and honor of bushido clash with the harsh reality of survival.

It will be the occasion for an epic where courage and a sense of honor will constantly be in the spotlight, but not in a simplistic sense. Kurosawa, with his unparalleled psychological depth, explores the nuances of these ideals: courage is not merely the absence of fear, but the ability to act despite it, often dictated by desperation or an almost romantic sense of duty, destined to clash with prosaic reality. Honor is a burden, a chain, a value that must be constantly redefined in the face of hunger, fear, and mutual distrust between classes. The initial distrust between the samurai and the peasants, who see the warriors as predators as much as the bandits, is one of the film's first acute observations on human nature and social barriers.

A superb sense of direction and a captivating storyboard make this work a monument of cinema and a benchmark for every industry professional. Kurosawa doesn't merely frame the action; he sculpts it. His camera is a dynamic entity, capable of long panoramic tracking shots that reveal the immensity of the landscape and the smallness of man, but also of intense close-ups that delve into the characters' souls. His audacious use of the telephoto lens, rare for the time, compresses space and intensifies movement, making the battles not only spectacular but visceral, almost claustrophobic despite the vastness of the settings. The meticulousness in planning, with extremely detailed storyboards that were then shown to actors and crew, allowed for an almost pictorial precision in every shot. No less masterful is his direction of actors, in particular the antithesis between Takashi Shimura's contained wisdom (Kambei) and Toshiro Mifune's wild, almost primordial energy (Kikuchiyo), who would become his cinematic alter ego par excellence. The mud and pounding rain of the final battle, filmed for weeks under extreme conditions, are not mere atmospheric elements, but characters in their own right, contributing to a narrative physicality rarely equaled.

“Seven Samurai” is not just a great film in its own right, but the source of a genre, the ultimate archetype, that would influence the genre for the rest of the century. Critic Michael Jeck suggests that this was the first film in which a team is assembled to carry out a mission, and instantly this narrative theme became a true pattern, a model for inspiration. One only needs to consider its direct re-elaboration in John Sturges' classic Western, The Magnificent Seven, but the influence extends far beyond: from the character dynamics in The Dirty Dozen to the construction of teams for impossible heists in films like Ocean's Eleven, up to sci-fi sagas where a group of heroes with different abilities unites to face a galactic threat. Kurosawa provided the universal grammar for every "band of brothers" or "fellowship" story.

And speaking of patterns, the film is literally permeated by them; repeated viewings of “Seven Samurai” indeed reveal recursive narrative patterns that have returned in works of decades to come. This is not just a narrative structure, but a worldview that permeates every scene. Consider the irony, for instance, in two emblematic sequences that reveal Kurosawa's acute, and sometimes cynical, view of human nature and the "mob."

In the first, the villagers have heard the bandits approaching, and run around in a panic, an almost grotesque image of collective terror. Kambei orders his samurai to calm and contain them, and the Ronin shuttles between groups (the villagers always run in groups, not individually) to round up the herd and order them to stay in their places. It is the archetype of the hero who must save humanity not only from external enemies, but also from its own self-destructive despair.

Later, after the bandits have been repelled, a wounded bandit falls in the village square, and now the villagers, with a surge of courage that is as belated as it is boastful, rush forward with torches and farming tools to kill him, a vengeful horde almost fiercer than the marauders themselves. This time, the samurai push them back with ill-concealed contempt, not because they feel pity for the bandit, but for the cowardice and opportunism of that posthumous courage. It is a sharp revelation of relative morality and the pragmatic, almost animalistic, nature of survival.

A true pattern of irony towards the herd-people, the human "herd," that would return in countless other works and that Kurosawa himself would further explore in films like Ran or Throne of Blood. This disenchanted gaze upon the masses, capable of opportunism and cruelty as much as resilience, is what elevates "Seven Samurai" beyond a mere adventure story. The final victory is bitter, melancholic, underscored by Kambei's words: "Once again, we have lost. It is the farmers who have won." The fields flourish, life continues for the villagers who adapt and prosper, while the remaining samurai are once again alone, their mission accomplished but their identity still precarious, their sacrifices almost forgotten in the inexorable cycle of peasant life. It is an epilogue that consecrates the film as a profound meditation not only on heroism, but on the loneliness of the hero and history's indifference to individual greatness.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...