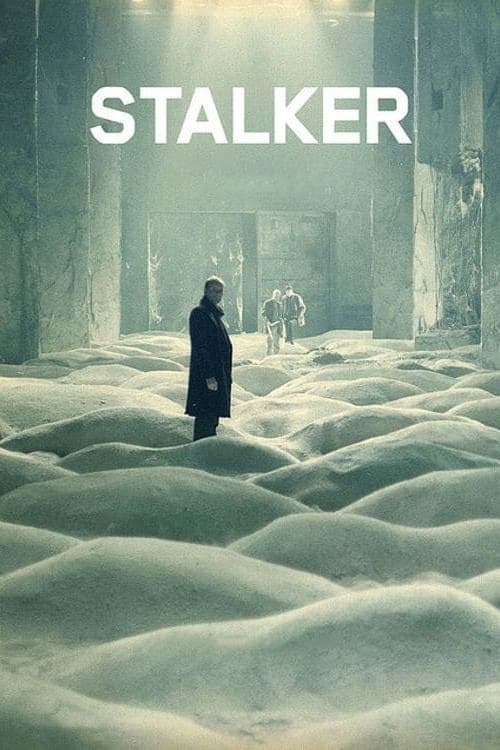

Stalker

1979

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A man stealthily climbs over a fence in the night.

He is a Stalker, one who knows the way and guides visitors into the Zone, a place forbidden by the Authorities after inexplicable events occurred within it. His role transcends the mere function of a guide, rising to that of an officiant in a secular rite, a priest of an undefined creed that holds the Zone as its profane sanctuary. He is not a hero in the conventional sense, but rather an archetype of the modern pilgrim, a contemporary Charon ferrying lost souls towards a limbo where hope is not guaranteed, but only the possibility of confronting one's innermost core.

Within the Zone exists the Room, the place where dreams can turn into reality, where questions receive answers. The Room, the epicenter of this mystical Zone, is not a mere dispenser of dreams, but rather a merciless mirror of the soul. It is said to grant the most recondite and sincere desires, not those superficial ones expressed in words or even those processed by the rational mind. It is precisely this unsettling honesty, this brutal absence of filter between the depths of being and its manifestation, that terrifies visitors more than the Zone itself. Man is confronted with the ultimate truth of himself, not with the illusion he constructs daily. This fear of authentic desire, of the unfiltered self, is a recurring theme in Tarkovsky's work, an urgent invitation to introspection that allows no compromise.

Traveling with him are the Professor and the Writer, two men adrift in life's turmoil, seeking a turning point. They embody universal archetypes: science and disillusioned intellect confronting ineffable mystery, faith and intuition as the sole compass in a world without coordinates. Their journey is a metaphor for the thirst for knowledge; the more reference points are lost along the way, the harder it is to attain ultimate wisdom. The Zone itself reveals itself not so much as a physical place but as a liminal space of the psyche, an interior desert dotted with traps that are not material, but existential. Every misstep is dictated not by a tangible danger, but by a metaphysical uncertainty, by the fear of confronting an authentic desire that the Room, paradoxically, might reveal with too much brutality.

The landscape they traverse is desolate, abandoned, ravaged by something indefinable. An indolent languor envelops everything, depositing the spores of abandonment, solitude, poisoning. Here, the landscape is not merely a backdrop, but an extension of the protagonists' state of mind: industrial ruins, stagnant water, wild vegetation reclaiming its domain—everything cries out for the abandonment not only of human structures but of certainties themselves. The chromatic palette, or rather its near absence – with the almost monochromatic tones of the initial sequences giving way to bursts of color only when the characters enter the Zone, an explosion of saturated greens and browns – is not a mere aesthetic flourish, but a language to distinguish the sterile and oppressive external reality from the vibrant, albeit dangerous, interiority of the Zone. Tarkovsky's direction is an immersion, a slow unfolding of meditative sequences that compel the viewer to slow their perceptive rhythm, to attune themselves to the slow and deep breathing of the work, amplified by a sound design that elevates every drop of water and every rustle to a symphonic element.

Another great film by Andrei Tarkovsky, adapted from a story by the Strugatsky brothers, "Roadside Picnic": obscure, shadowy, diaphanous, expansive, and imperceptible, like a verse by Dylan Thomas whispered in the night. Tarkovsky, while starting from the narrative core of the Strugatskys, profoundly deviates from it, sublimating science fiction into a metaphysical parable. Where the novel focuses more on the artifacts and material mysteries of the Zone, the Soviet director strips the narrative of any facile sensationalism to concentrate on the inner odyssey, transforming the genre into pure visual philosophy.

A headlong dive into the darkest recesses of human feeling, of a hostile and unknowable reality, of a pervasive and inescapable malaise. The genesis of Stalker is itself a Tarkovskian odyssey. The film was shot under grueling conditions, plagued by technical problems and a tormented production that saw entire sections discarded and reshot due to the destruction of the original negative. This "second birth" of the film, in which Tarkovsky decided to start almost from scratch, is not just a production anecdote but a sign of his relentless pursuit of perfection, an obsession reflected in the meticulousness of his shots and the depth of his themes. It is said that the very water in which the protagonists are immersed was polluted, a tangible metaphor for the malaise permeating the film and perhaps Soviet society itself at the time, even before the premonitory echo of the Chernobyl disaster, with which many critics have erroneously – or perhaps intuitively – associated the desolation of the Zone.

But also an attempt to provide an explanation: "What resonates within us in response to noise elevated to harmony? And how does it transform for us into the source of immense pleasure?" One cannot help but sense in this aimless wandering an echo of Kafkaesque labyrinths, of Beckettian vain waiting, but here the absurd merges with a palpable spirituality, even if not dogmatic. The disquiet is existential, but the search is transcendent. The final question is an almost mystical invitation to perceive the unheard, to translate the chaos of existence into a comprehensible melody, a search for beauty and meaning despite everything.

Tarkovsky continues his journey into the Monad Man: what moves us, what drives us to continue, what goals can we set for ourselves? Stalker is the ideal complement to Solaris; man is alone before his nightmares. But if in Solaris the origin of the nightmare was emotional, projected by a sentient ocean that materialized the characters' guilt and repressed desires, a cosmic entity that mirrored the unconscious, in Stalker it is exclusively intellectual. Here the Zone is not a sentient entity in the same way, but a catalyst, a filter through which "neuronal waste" – those stratifications of fears, false objectives, intellectual self-deceptions – are laid bare. Man does not fight against an external enemy or an alienation that transcends him, but against his own intrinsic fallibility, against the snares of his own mind that lead him astray from true desire. The Zone is the secular purgatory where the soul, stripped of all superstructure, must confront its own emptiness or its most uncomfortable truth, the neuronal waste with which man must contend to be able to reach the ultimate goal, if indeed it exists, or perhaps to accept that the goal itself is the arduous path, the endless search.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...