Stranger Than Paradise

1984

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Jim Jarmusch in his second film after his debut with Permanent Vacation in 1980. With Stranger Than Paradise, the young Jarmusch not only consolidated his status as an unmistakable voice in the American independent film scene but also defined a stylistic language that would perpetually characterize his filmography: a dry minimalism, a melancholic humor, and a predilection for non-events that paradoxically turn out to be the most significant occurrences.

The talented New York director offers us a grotesque and sardonic work, a road movie where everything happens and where everything unexpectedly returns to its exact starting point after an incredibly convoluted journey. But simply labeling it a "road movie" would be reductive, almost a betrayal of Jarmusch's intent. It is rather an "anti-road movie," a disillusionment of the adventurous rhetoric typical of the genre, where the freedom of the road transforms into aimless wandering, permeated by a sense of existential disorientation. The urban and rural landscapes traversed are not picturesque backdrops for cathartic revelations, but rather extensions of the characters' inner desolation. The grainy black and white, an aesthetic choice as radical as it was economically necessary (the film originated from a thirty-minute short, "The New World," later expanded), amplifies this sensation of timelessness and alienation, stripping America of any mythical luster to reveal a crude and indifferent reality.

The story is that of a young New Yorker, Willie, bored and cynical, who receives an unexpected visit from his sixteen-year-old Hungarian cousin. Eva, an almost alien figure in the American context, brings with her an innocence and curiosity that clash with the apathy of Willie and his friend Eddie. Their dialogues are fragmented, punctuated by awkward silences, a faithful reflection of a generational inability to communicate authentically, to establish meaningful connections. It is in this dance of misunderstandings and small gestures that the film's true drama lies, a drama whispered rather than shouted.

After ten days, the girl moves to Cleveland. Willie, unable to tolerate the void left by her departure, though he would never admit such emotional weakness, decides to act.

To combat boredom, Willie, along with his friend Eddie, returns the visit to his cousin by traveling to Cleveland. A journey not for discovery, but merely as a filler, to escape the cumbersome weight of nothingness that looms over their existence. The characters do not seek answers, but only distraction from the void. Their relationship is woven with unsaid things, with an awkward and almost involuntary affection, a parody of family and friendly dynamics. Eva's arrival in their monotonous apartment is a crack in the routine, but their reaction to it is also an attempt to restore a precarious balance within the monotony.

The journey will mark the beginning of a grotesque slalom through the currents of fate and the road. Fate, in Jarmusch's cinema, is not a transcendent force but rather a series of banal coincidences, illogical detours that lead to no epiphanies, only to new configurations of the same, implacable boredom.

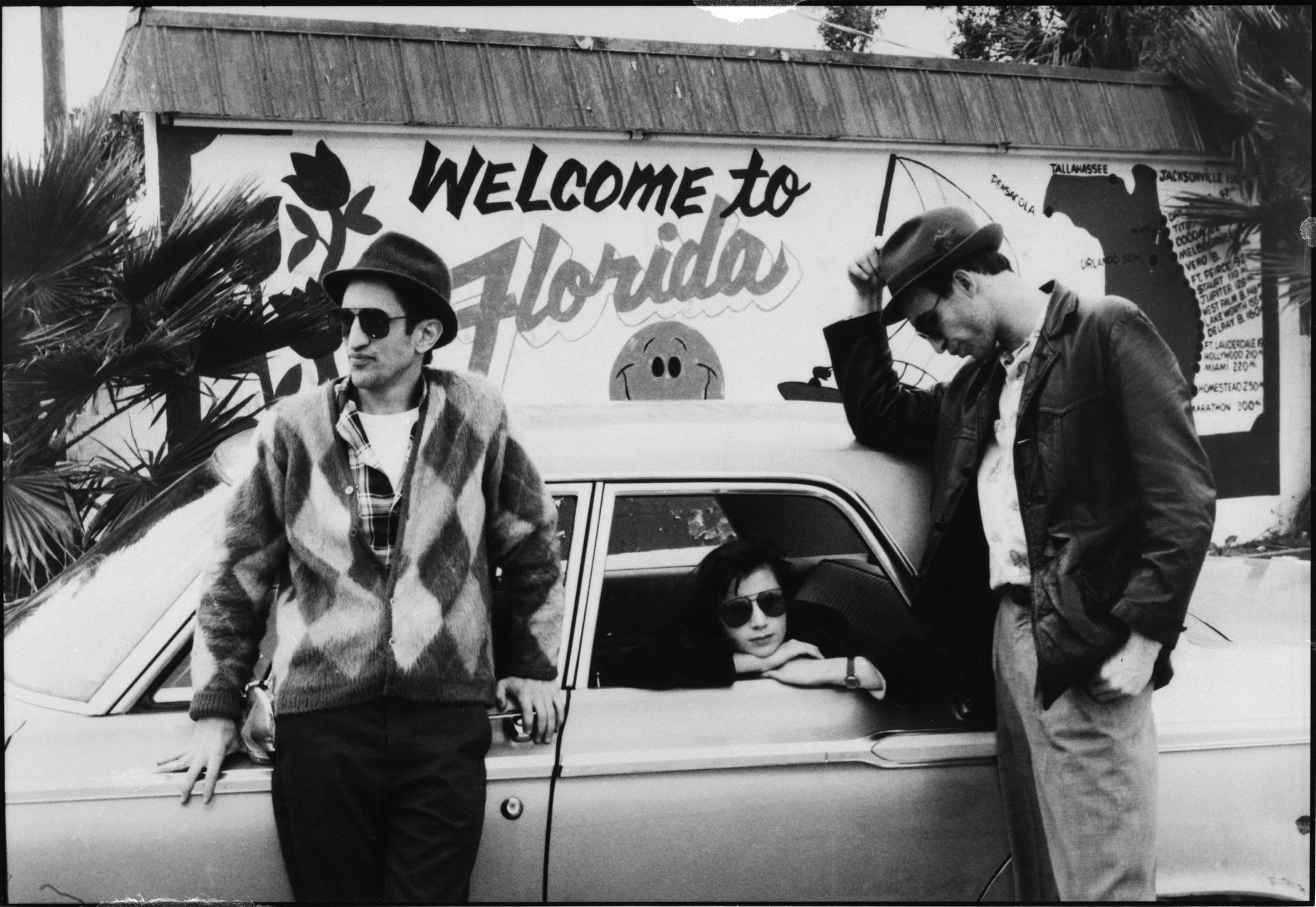

Upon arriving in Cleveland, Willie and Eddie involve Eva in a trip to Florida. A further stage in an odyssey of the absurd, where "paradisiacal" Florida proves to be just as desolate and devoid of promises as the icy streets of Cleveland or the alleys of New York. This systematic disillusionment with the American myth is a leitmotif. The dream of a land of opportunity crumbles in the face of the concrete reality of anonymous motels, faulty televisions, and deserted beaches, confirming that paradise, if it exists, is indeed stranger than reality itself.

The journey as a metaphor for life is a constant in Jarmusch's cinema; we will find it again in Down by Law, in Dead Man (where it takes on the value of a cathartic path). But while in Dead Man William Blake's pilgrimage is a slow and inexorable transformation towards spiritual enlightenment and death, in Stranger Than Paradise the journey is circular, an eternal restart without true progress. It is more akin to a perpetual escape, an unsuccessful attempt to evade themselves and their condition. This poetics of stasis in motion is a Jarmuschian trademark, a keen reflection on modernity and the difficulty of finding meaning in an increasingly disenchanted world. The constant ticking of Screamin' Jay Hawkins' "I Put a Spell on You," the only truly diegetic and recurring musical element, serves as a hypnotic soundtrack to this existential wandering, a spell that traps and fixes the characters in a limbo.

A commendation to the hieratic John Lurie in the role of the protagonist; his undecipherable mask lends credibility and substance to the work. His performance, as well as that of Eszter Balint as Eva and Richard Edson as Eddie, is deliberately anti-acting. Their inexpressive faces, minimal gestures, and lines delivered with an almost Zen-like detachment are not a sign of a lack of talent, but rather a precise artistic choice that reflects the characters' apathy and alienation. This "deadpan comedy" is a cold and subtle humor, not aiming for booming laughter but for a bitter, knowing smile.

Willie and Eddie physically move to Cleveland, but their journey is not a physical transfer from point A to point B, but a kind of intellectual equation, an inference launched into the dark of night. This is the pulsating heart of the film, its boldest insight. The metaphor of the journey is not simply tied to movement in space, but to the activation of a mental process.

The journey, according to the concept of Stranger Than Paradise, must first be caressed in the mind, planned, lived cerebrally, even before being experienced. It is not the destination that matters, nor the path itself, but rather the anticipation, the mental construction of the event. This pre-lived experience, this "heuristic experience" as the critic defines it, is the only true act of freedom and creation possible for the characters.

When the car devours the kilometers separating it from the final destination, the journey is actually already complete; it is merely about carrying out the heuristic experience. It takes shape as an act of mere formality, a reproduction of a path already drawn in the mind. Life, from this perspective, is not a sequence of unpredictable events, but a series of rituals, of predefined paths, where surprise is banished and boredom reigns supreme. Stranger Than Paradise thus stands as a manifesto of cinema that rejects spectacularization and excess, embracing instead the intimacy of the everyday, the poetry of the unsaid, and the unsettling beauty of routine. A masterpiece that redefined the aesthetic of American independent cinema, demonstrating that to explore the depths of existence, special effects are not needed, but only a keen gaze and a profound understanding of the human soul.

Genres

Countries

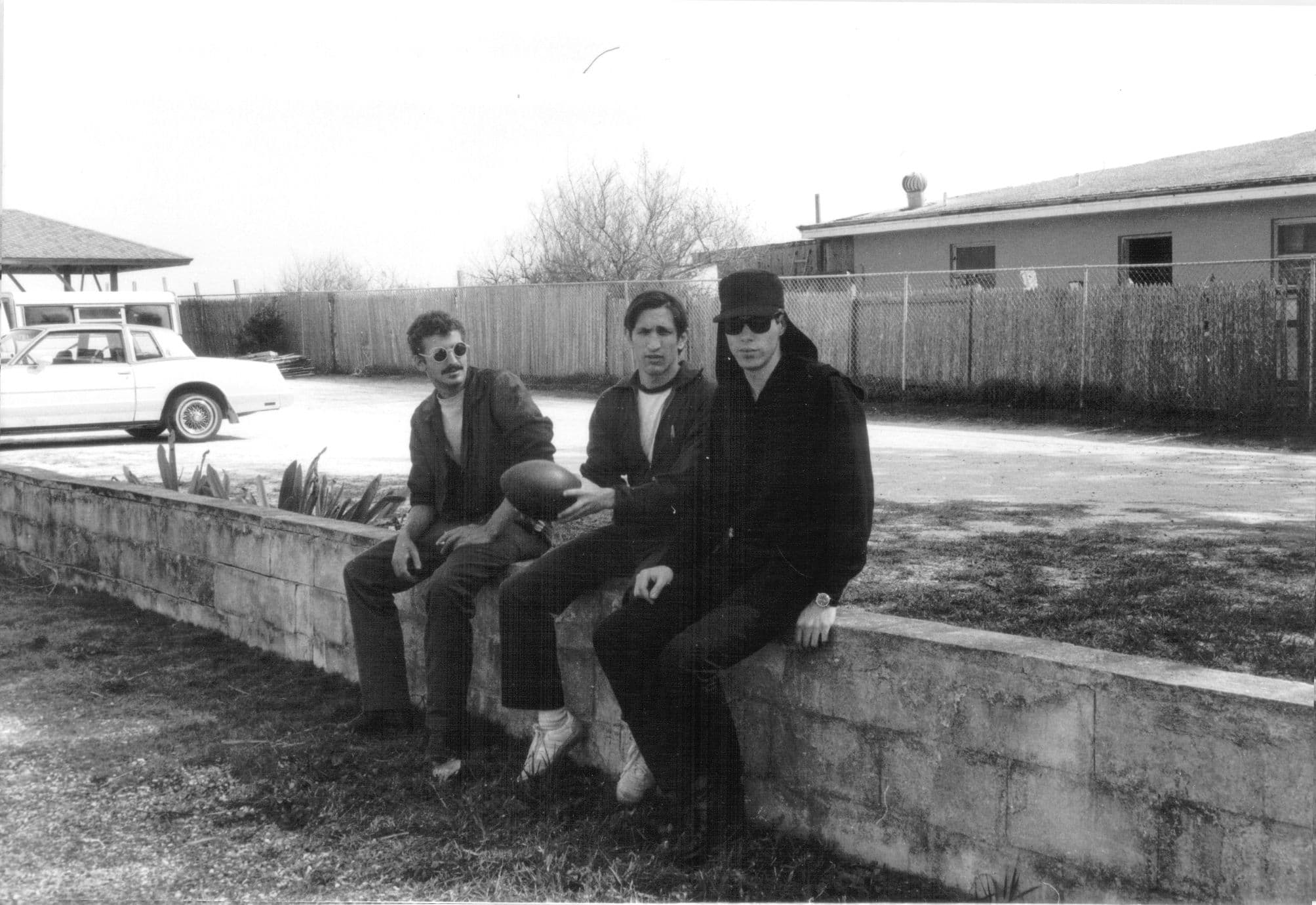

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...