Taxi Driver

1976

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Travis Bickle is a Vietnam veteran repurposed as a taxi driver, a flayed soul bearing the invisible yet lacerating marks of a conflict that expelled him from normality and cast him into a post-war wasteland, where heroism is just a faded memory and disillusionment the current currency. He lives as a misfit on the fringes of society, his agonizing solitude reverberating between the four walls of his apartment, a suffocating cubicle that reflects the prison of his mind. It’s an existence on the fringes, almost monastic in its deprivation of meaningful human connections, which makes him a prototype of urban alienation, a theme so dear to 1970s American cinema, from Midnight Cowboy to Serpico, in which the city itself becomes a character, a sprawling, sick megalopolis.

His only contact with the outside world is when he drives, during those interminable nocturnal hours that see him navigating the wet streets of New York. Before his eyes, the city nights unfold in a gallery of rot and indecency so profound as to saturate him, to deeply sicken him. It's not just the visible dirt or the sweat of bodies, but a moral miasma that infiltrates, accentuated by Michael Chapman's livid cinematography, which transforms the alleys and neon lights into a palette of sickly greens and infernal reds, almost expressionistic. Travis's New York is a modern Dantesque hell, a decadent Babylon that he, in his messianic delusion, feels an urgent need to purify.

He falls in love with a political activist, Betsy, a luminous and unreachable figure who embodies the purity and idealism of a world from which Travis is irremediably excluded. His clumsy attempt to court her, culminating in taking her to see a pornographic film, is not just a social gaffe, but a chilling symptom of his total communicative dysfunction, of his inability to decode the elementary rules of human interaction. It is proof that his inner compass is broken, irremediably faulty.

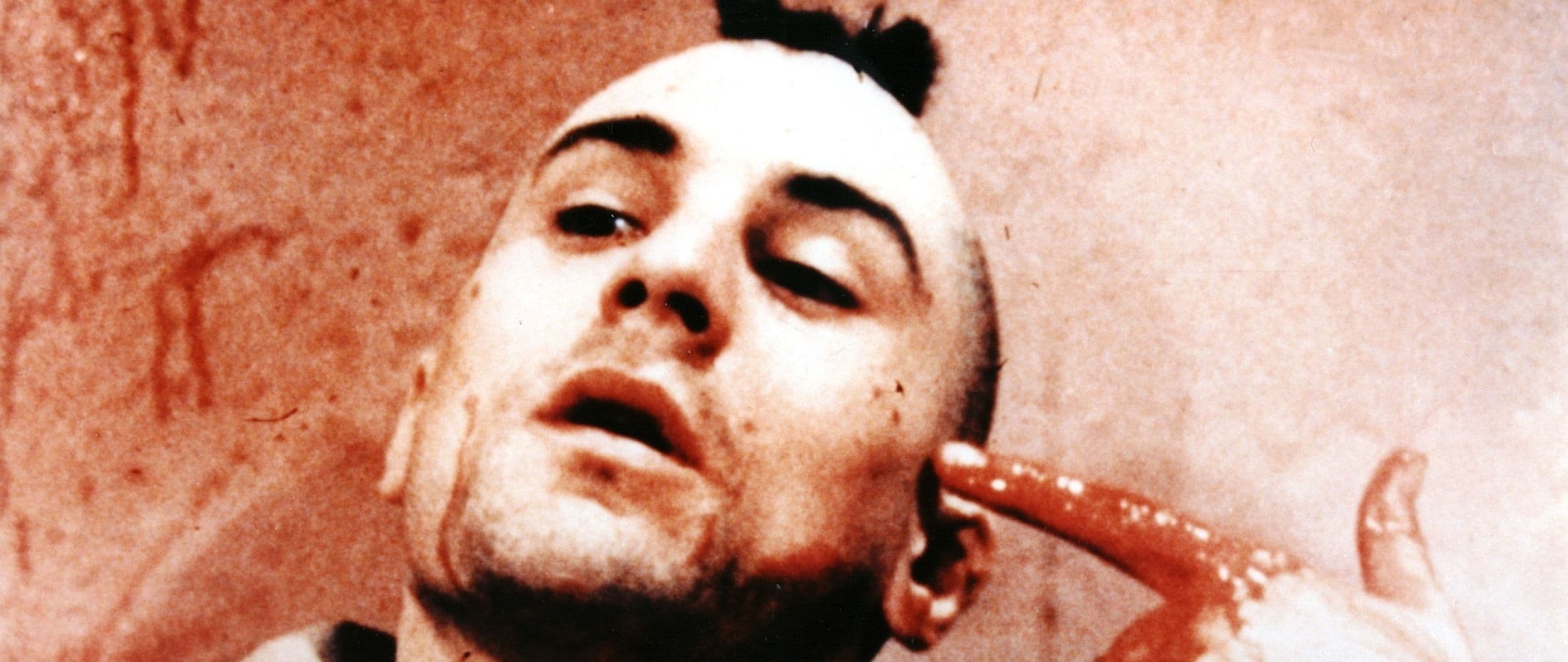

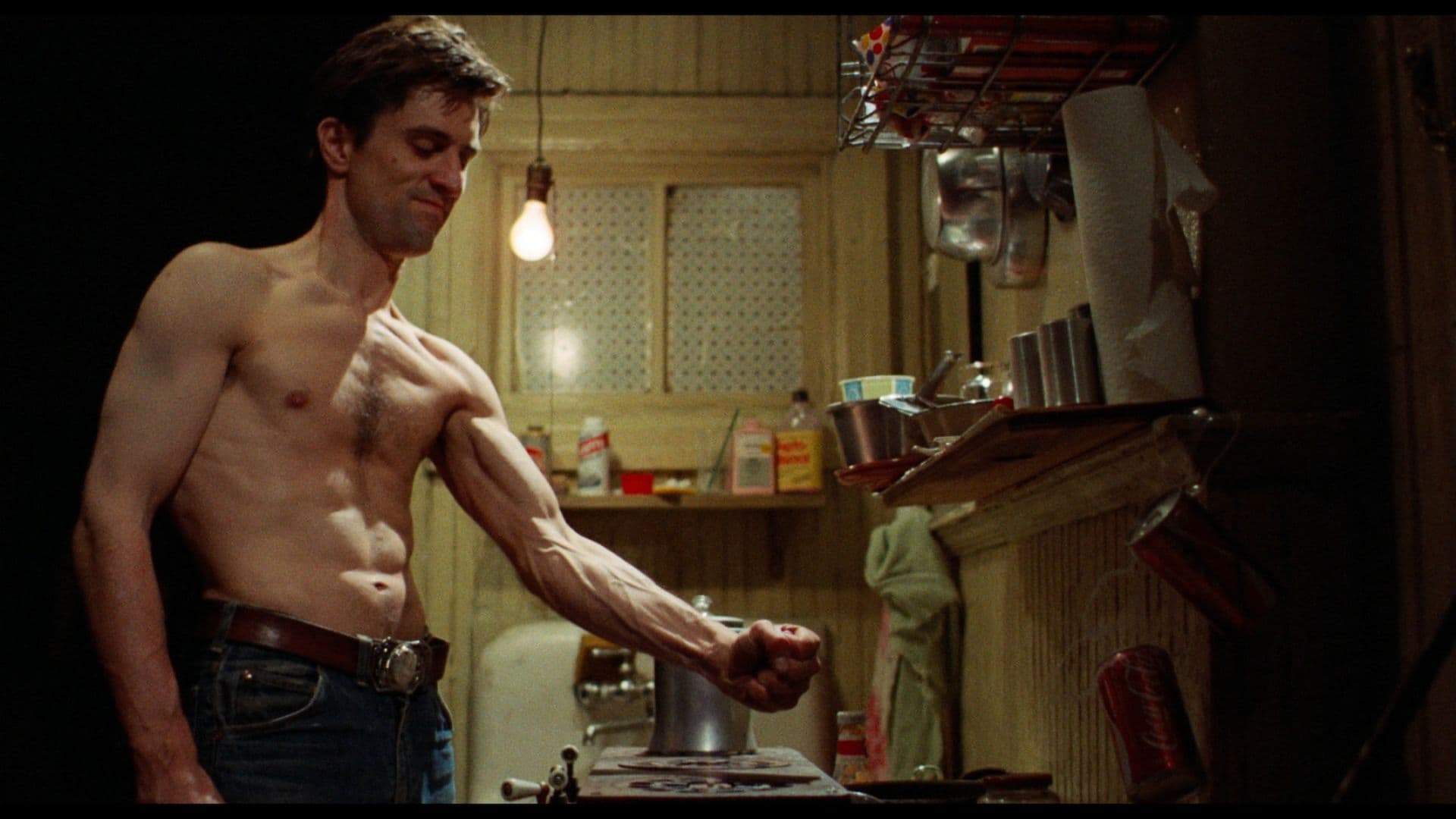

The continuous injustices the man witnesses – sordid violence, rampant corruption, generalized indifference – not least the mistreatment of a minor prostitute, Iris, will plunge him into a state of total denial, where external reality deforms and collapses under the weight of his inner torment. The scum surrounding him, that moral mud he perceives everywhere, will osmically merge with his inner anguish until it envelops the world around him, making it explode. He is no longer just an observer but transforms into an agent, his personal avenger of justice, in a gesture reminiscent of a Dostoevskian character's descent into moral abjection, a kind of American Raskolnikov without the possibility of intellectual redemption. His physical metamorphosis, the obsessive training, the mohawk haircut, are ritualistic steps towards a self-anointment that culminates in the paroxysm of violence.

Through Iris's redemption, or rather, through his determination to snatch her from the clutches of her exploiter, Travis glimpses a hope of salvation, an opportunity to shake off the filth that covers him. This personal crusade, though bloody and delusional, offers him a momentary purification, a way out of his unbearable solitude. However, the ambiguous, almost mocking ending, which sees him acclaimed as a hero, leaves the viewer with a bitter aftertaste and the persistent question: was it true redemption or just another collective hallucination, yet another proof of the blindness of a society incapable of recognizing the pathology behind the violence?

The cornerstone of this work remains the psychological X-ray of the protagonist and his inexorable descent into madness. Scorsese, with Paul Schrader's visceral screenplay (deeply influenced by Camus, Sartre, and Robert Bresson's Pickpocket), immerses us into Travis's psyche with such intensity that the line between reality and distorted perception becomes blurred. Robert De Niro's performance is legendary: his dedication to method acting, having driven a taxi for weeks in New York to immerse himself in the character, his iconic improvisations, gave birth to a cinematic icon of despair and paranoia.

The memorable scene, etched into our collective imagination with the force of an archetype, is the one where Travis confronts his reflection in the mirror with weapons in hand, addressing it with a menacing: “You talkin' to me?” It is a moment of pure schizophrenia, an externalized inner dialogue, a dress rehearsal for his imminent, inevitable violent collapse. That monologue, the result of De Niro's improvisation, has become the battle cry of every desperate soul who feels at war with the entire world.

The beauty and disquiet of Taxi Driver lie precisely in its metamorphosis of the concept of violence. First, a tangential vision of violence: glimpsed fleetingly in the streets, through the dirty windows of Travis's taxi, a background noise of the metropolis. Then, a violence that crackles like a fire under the ashes in Travis's soul, repressed and resurfacing at times in his bewildered and paranoid behaviors, in his feverish gazes. Finally, violence in all its ruthless power erupts, engulfing all Reality, a bloody catharsis that, far from purifying, leaves a veil of horror and ambiguity. Bernard Herrmann's soundtrack, his last, is a masterpiece in itself, a jazz-noir accompaniment that with its strident and melancholic notes, almost a suite of torments, amplifies every tremor of Travis's soul.

Almost a clinical document, then, which the director compiles with ruthless cinematic lucidity, almost a chronicler who follows a man's descent with glacial professionalism, without explicit moral judgment, but with surgical precision in investigating the depths of a troubled mind. Taxi Driver is not just a film about violence, but a disturbing exploration of solitude, mental illness, and the absence of meaning, projected against a backdrop of post-Vietnam social unease that made America fertile ground for the birth of anti-heroes and borderline figures. Its influence has been enormous, a beacon in the psychological thriller genre and a model for generations of filmmakers, a timeless work that continues to question us about the dark side of the human soul and the violence inherent in society.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...