The Battle of Algiers

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The Battle of Algiers is one of those rare gems set in the diadem of Italian cinema from the magical decade of the sixties, capable of garnering unanimous public and critical acclaim not only in Italy but especially internationally. A decade, the 1960s, that saw Italy as the protagonist of an extraordinary cinematic flourishing, from Commedia all'italiana to masters like Fellini and Antonioni, but Pontecorvo stands out for his ability to infuse historical narrative with vibrant topicality, transcending mere chronicle to embrace a universal epic of the struggle for self-determination. Its global resonance was no accident, but the result of a staging as aesthetic as it was ideological, capable of speaking to the heart of post-colonial liberation movements and, at the same time, questioning Western democracies about the shadows of their own colonial past.

A work commissioned by the Algerian government that sparked considerable controversy in France, with a large part of French institutions branding it as having too partial a view of the facts. This accusation of partiality, far from unfounded in the eyes of a nation that still struggled to acknowledge the true nature of its presence in Algeria, reveals the incendiary power of a work that, while adopting a rigorous quasi-documentary style, dared to show the brutality of colonial repression with disarming frankness. The film thus became a cultural and political casus belli. It was for this reason that the film was censored and had to wait five years before it could be released in French cinemas, in a re-edited version, a sanitized version that sought to attenuate the impact of a message deemed too subversive, too uncomfortable. Paradoxically, this very ostracization fueled its myth, making it a counter-culture icon and a reference text for the study of guerrilla and counter-guerrilla techniques even in Western military circles, including the Pentagon itself.

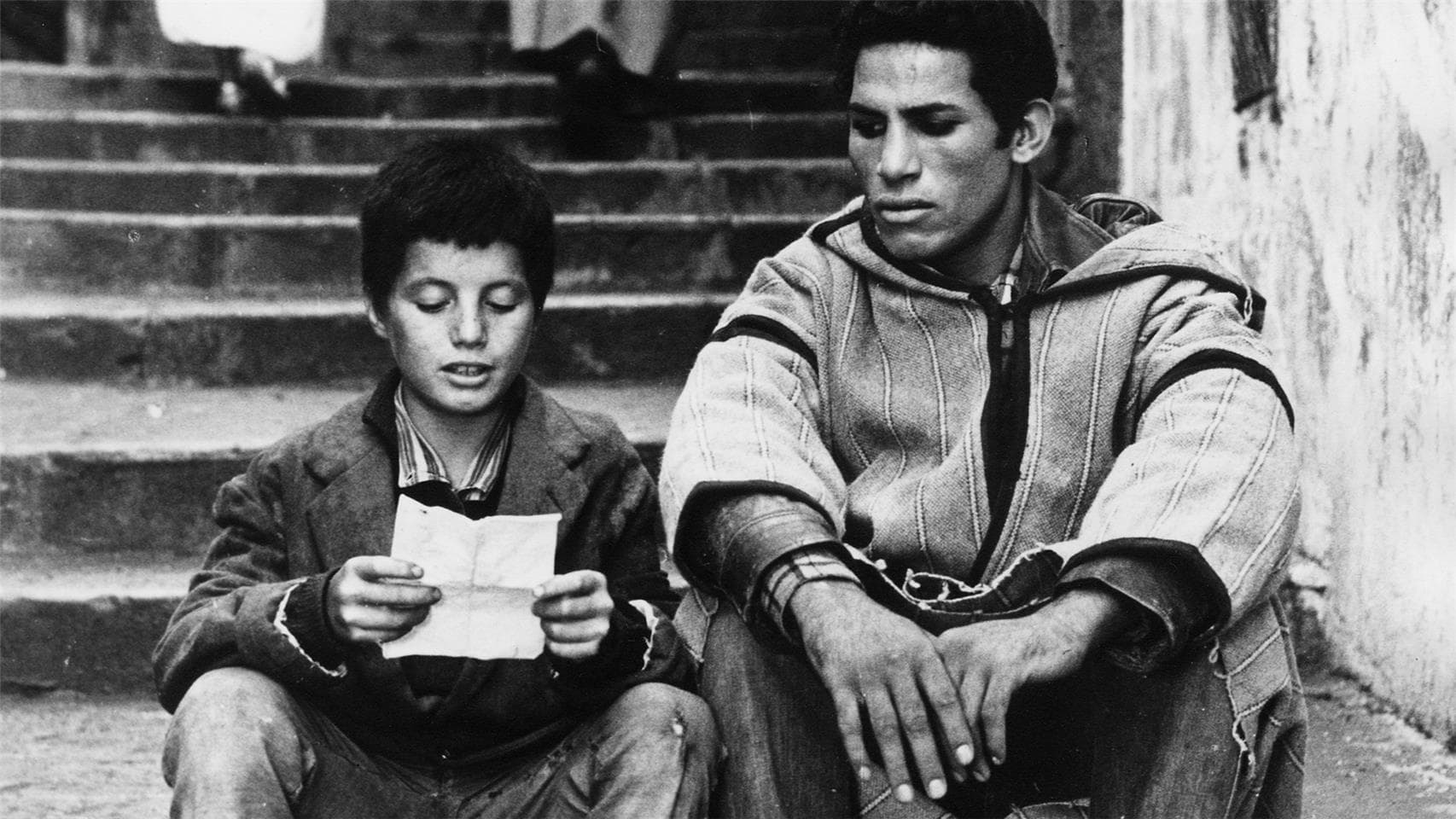

Gillo Pontecorvo, thanks also to the fervent pen of a Solinas at the height of his powers, paints an ethereal and teeming Algiers, where the French army bloodily suppresses the 1957 independence revolt. Pontecorvo's mastery, forged in the crucible of neorealism but projected towards a unique synthesis of documentary starkness and epic breadth, manifests in his ability to bring out the pulsating tension of the city, transforming the alleys of the Casbah into a Shakespearean theatre of freedom and oppression. Solinas, for his part, does not merely reconstruct events; he chisels the dialogues, imbues characters with psychological depth, and structures the narration with surgical precision, elevating chronicle to universal drama. His screenplay is a model of balance, capable of representing the ethical complexity of a conflict where right and wrong intertwine with disarming clarity.

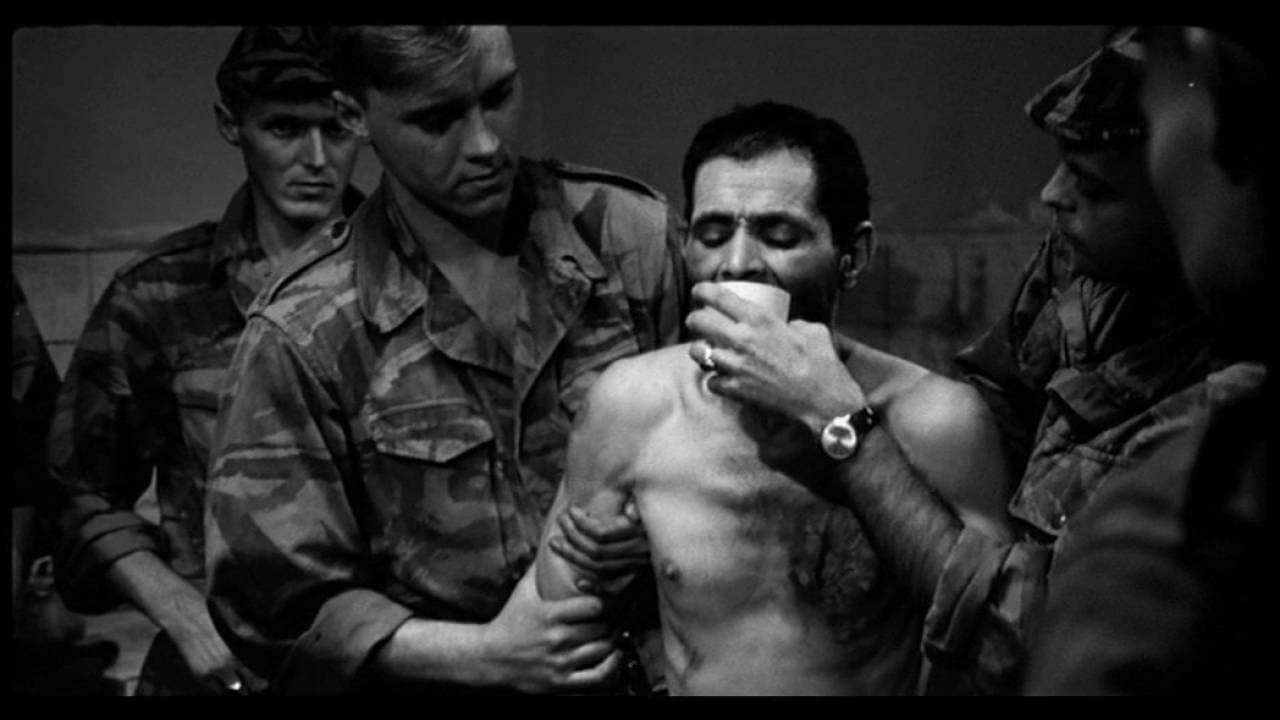

It is precisely thanks to one of the leaders of that revolt, Ali La Pointe, who became a martyr in those bloody days, that three years later the Algerian people managed to fulfill that yearning for liberty. But the work does not merely celebrate the figure of the revolutionary hero; it probes with relentless acuity the psyche of the colonizer and the colonized. On one hand, the intransigent idealism of Ali La Pointe, a man of the people drawn into History; on the other, the glacial yet intellectually fascinating figure of Colonel Mathieu, portrayed with sober intensity by Jean Martin, who embodies the implacable logic of raison d'état and psychological warfare. The film is a moral labyrinth, questioning the legitimacy of violence in the name of freedom and the intrinsic brutality of counter-insurgency. There is no Manichaeism: Pontecorvo shows us how the spiral of violence deforms the humanity of both sides, laying bare the atrocious cost of decolonization and the paradox of freedom gained through means often no less cruel than those fought against.

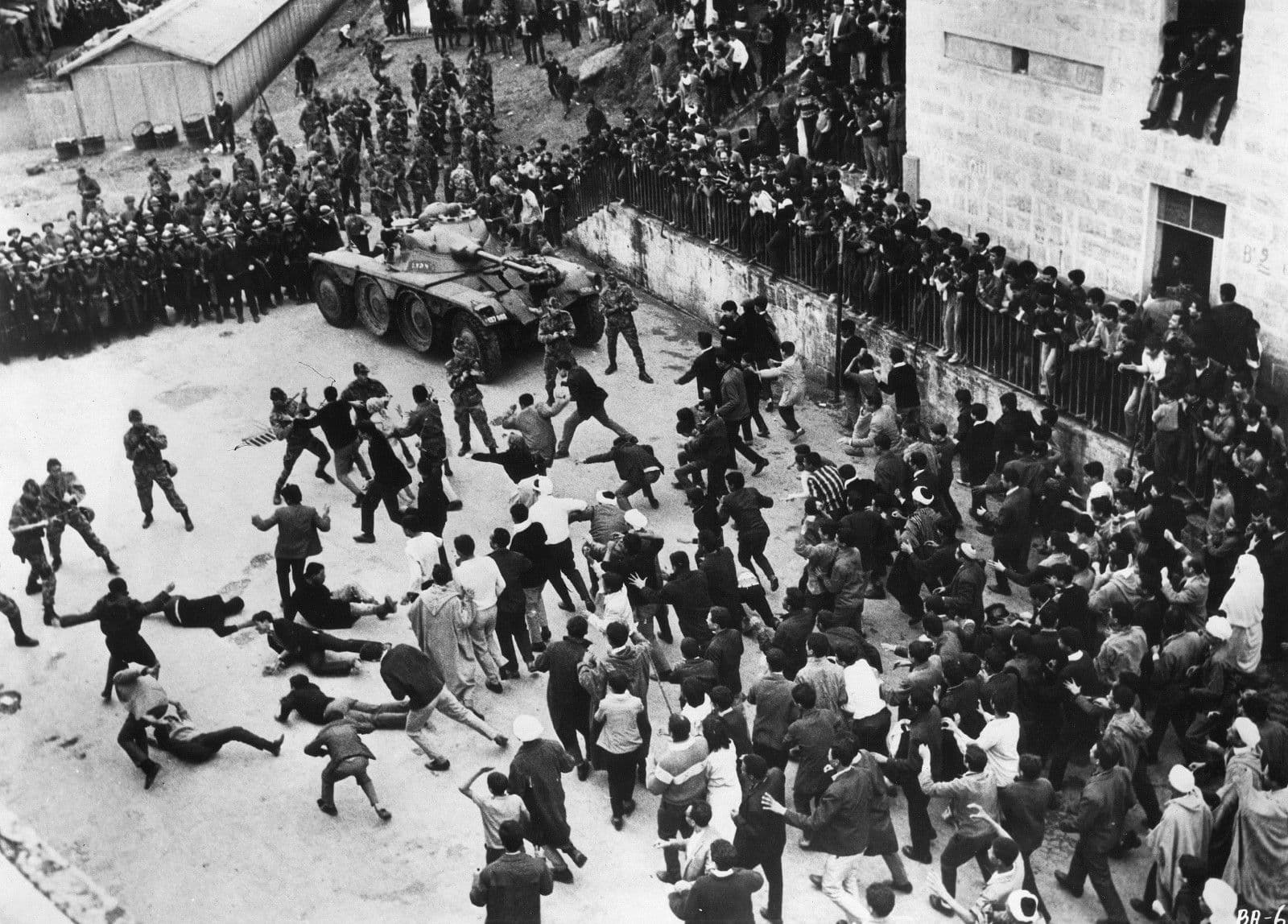

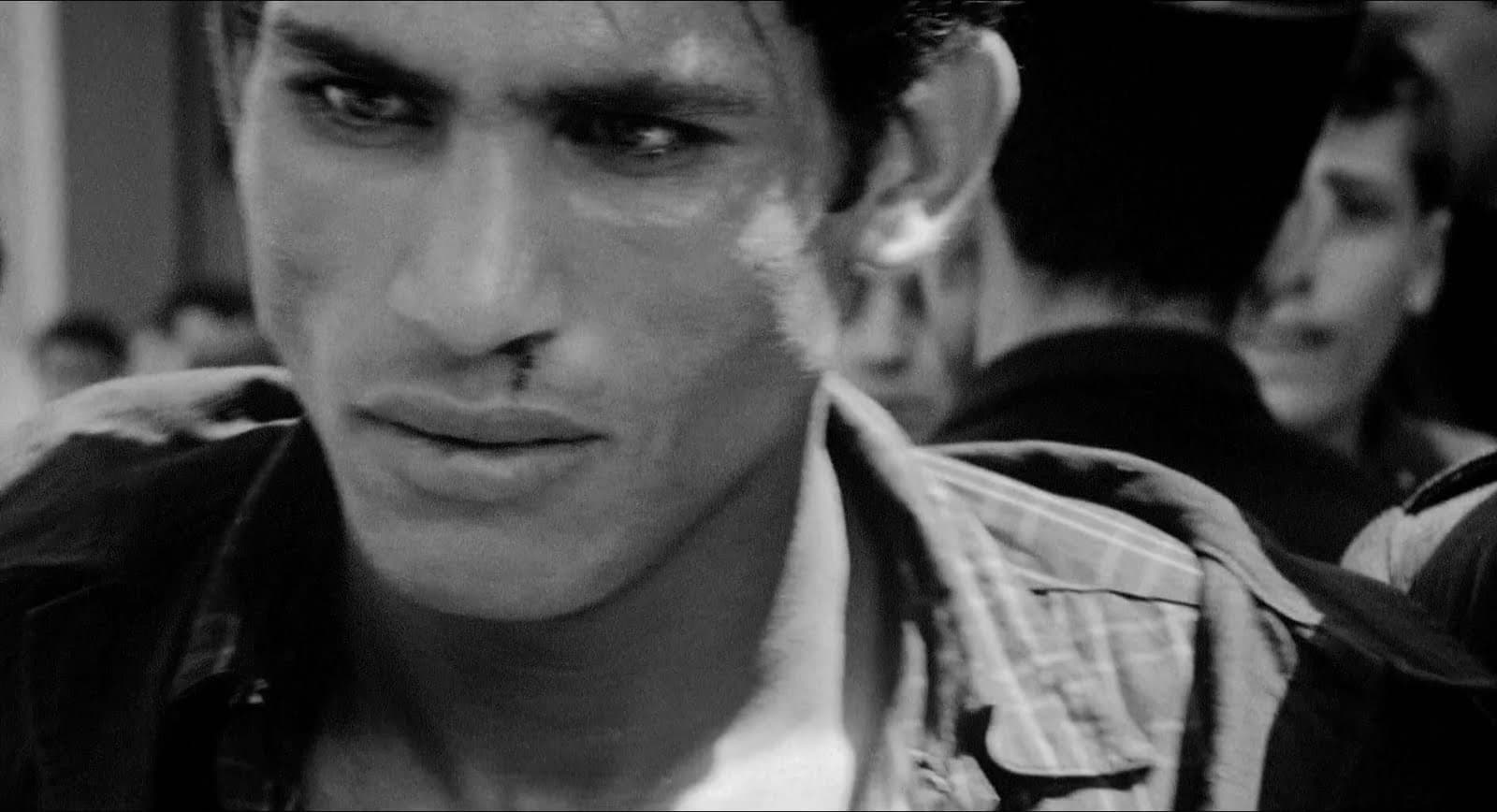

A work entirely shot in an exceptionally elegant black and white, featuring epic scenes of urban guerrilla warfare, with a stunning soundtrack by Ennio Morricone. The black and white, far more than an aesthetic choice, is a declaration of intent: it lends the film the grainy, authentic patina of a historical newsreel, blurring fiction with historical documentation and enhancing the sense of immediacy and truth. Marcello Gatti's cinematography is sublime in capturing the severe beauty of the Casbah and the controlled chaos of the clashes. The urban guerrilla scenes, shot with breathtaking realism, are the result of meticulous reconstruction work and the skillful use of a handheld camera, which immerses the viewer in the heart of the action, lending a palpable urgency to every sequence. Ennio Morricone's soundtrack, with its pounding percussions and poignant melodies that merge with traditional Algerian chants and the deafening noise of the clashes, is another fundamental piece of this sensory mosaic. It does not merely accompany the images, but becomes an integral part of the narration, amplifying the pathos and tension, and helping to indelibly sculpt the images and sounds of a troubled era into the collective memory. "The Battle of Algiers" is not just a film; it is a cinematic monument to the tenacity of freedom, a universal warning about the complexity of armed struggle, and an inexhaustible source of debate on history, politics, and ethics, whose resonance shows no signs of diminishing, establishing itself as an enduring classic that continues to question our present.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...