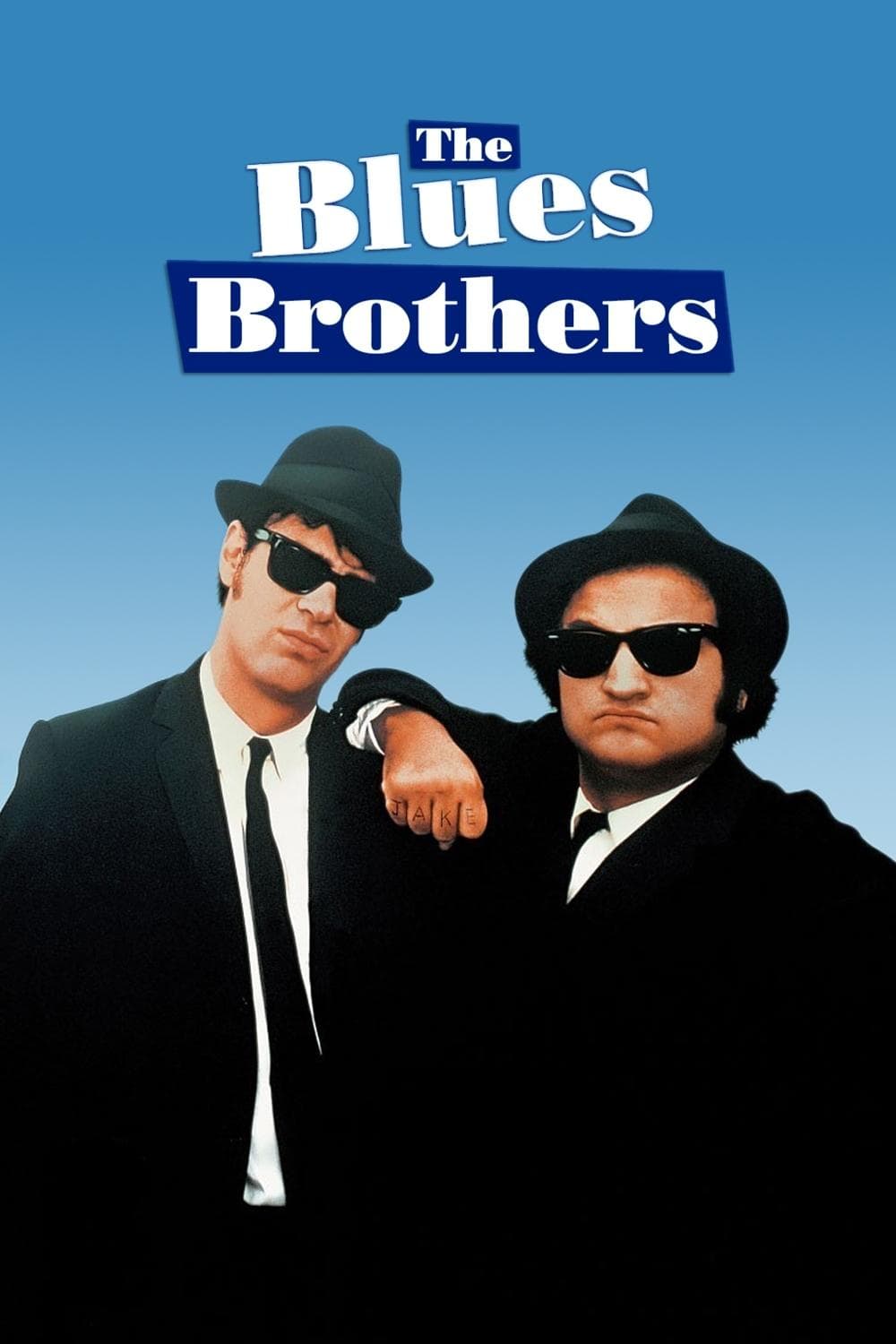

The Blues Brothers

1980

Rate this movie

Average: 2.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

John Landis, with his unmistakable irreverent touch and his predilection for controlled anarchy, directed this lighthearted and inimitable film in 1980, a work that transcends simple comedy to become a true anthem to music and freedom. Leveraging the exuberant comedic talent of John Belushi and the brilliant yet measured madness of Dan Aykroyd – a duo already iconic from Saturday Night Live, from which the characters of Elwood and Joliet Jake Blues had taken form and vigor – Landis sculpts an unprecedented urban epic. The two brothers, disheveled, foul-mouthed, and irreverent, emerge from the mire of imprisonment and precarious existence, ascending to the role of quasi-saints, guardians of a "mission from God." This is not a trivial clerical precept, but rather a divine illumination, a categorical imperative received directly from a reverend with the face of James Brown, which compels them to save an orphanage in their neighborhood from bankruptcy. A Soul Crusade, one might call it, where faith is placed not in dogma, but in rhythm, harmony, and the redemptive power of the blues.

With the urgency of those entrusted with a sacred task, they decide to reform the legendary Blues Band. Their strategy is to recruit the old guard, the former members scattered across Chicago and beyond, ensnaring them with dazzling promises of non-existent gigs, but above all with the undeniable magnetism of a cause greater than themselves. It is in this metropolitan pilgrimage that the film transforms into a true sonic pantheon, a living tribute to the history of African American music.

On their path, which is simultaneously an itinerant stage, names of the caliber of Aretha Franklin, with her unparalleled interpretation of 'Think' in a dilapidated restaurant; Ray Charles, who transforms a musical instrument store into a gospel temple with 'Shake a Tail Feather'; the legendary Cab Calloway, who, with the elegance of another era, brings 'Minnie the Moocher' back to life; and the ecumenical James Brown, preacher and performer, whose 'Old Landmark' is an explosion of spirituality and funk, pass through and perform. These are not mere guest stars or musical cameos; they are full-fledged show numbers, integrated into the narrative with such fluidity that they become key plot points themselves. The film acts as an essential cultural vehicle, bringing these giants of music to a younger audience, honoring their legacy and demonstrating their eternal vitality.

And while music is their creed, chaos is their language. The Blues Brothers' journey is marked by a sequence of apocalyptic events that defy all physical logic, transforming Chicago's urban landscape into a playground for calculated anarchy. Amidst colossal chases that stage the destruction of hundreds of vehicles – a true kinetic ballet reminiscent of both early slapstick and the car choreography of Chuck Jones cartoons, in a riot of metal and smoke that cost the production mind-boggling sums – soul-stirring blues ballads, the unexpected intervention of surface-to-air missiles, homemade flamethrowers, phone booths blowing up in a parade of surprising practical effects, and entire shopping malls devastated by the mythical Bluesmobile, their unstoppable steed, the film unleashes a hyperbolic comedy that isn't afraid to dare. Even an improbable platoon of Illinois Nazis, grotesque and absurd figures who serve as antagonists as ridiculous as they are tenacious, joins the chase, representing yet another surreal obstacle on a path already beyond all imagination. The two Blues brothers, Elwood and Joliet Jake, with their impassive determination behind dark glasses, must evade all these unleashed forces to reach their final destination before the predetermined deadline: the County tax office, the bureaucratic altar where they must deposit the payment that will save the institution where they grew up, their only true home.

This monumental work was evidently born with the primary intention of honoring and, in a sense, eternalizing Black American music, an intention ennobled by a soundtrack that is not only explosive but intrinsically narrative. It could not have been otherwise, given the project's musical pedigree. The music is not a mere accompaniment, but the pulsating heart and propulsive force of the entire film, a true auditory script that guides and comments on every action. Likewise, the pyrotechnic screenplay, written collaboratively by Landis and Aykroyd with a verve that alternates the wildest nonsense with moments of acute social observation, is a perfect mechanism of cause and effect, or rather, chain reactions. Every device is fatally linked to the next, in an unstoppable crescendo of absurdity and comedic genius, just as every musical piece fits into the plot, sometimes pausing it for a moment of pure performative ecstasy, sometimes accelerating its rhythm. The narration is damnably effective precisely because of this relentless progression, granting no respite to the viewer and dragging them into a whirlwind of events as unpredictable as they are inevitable.

The film is a true catalog of memorable scenes, each worthy of analysis and applause, and choosing a favorite is an arduous, almost unfair task. Yet, if we were to venture a selection, the instant when Jake takes off his dark glasses and, with his magnetic and almost melancholic gaze, ensnares for a single, fatal moment a fiercely armed ex-girlfriend with a submachine gun (the unforgettable Carrie Fisher, in a role that is pure caustic fun), remains etched in memory. It is a moment of rare vulnerability for Jake's otherwise unmovable character, a glimpse of the man beneath the icon, a surreal pause in the blind fury pursuing him. Fisher, here, is an almost mythological figure of comedic revenge, a mini-skirted Erinys, whose vengeful determination is as terrifying as it is hilarious.

Beyond the aforementioned music giants, the gallery of cameos is a true hidden treasure, a who's who of pop culture and music of the era. Many well-known faces, each with a fleeting but incisive presence: John Candy, in the role of the amiable but unfortunate investigator who follows their tracks with an almost touching dedication; Steven Spielberg, in a brief but iconic appearance as a tax clerk, a symbol of the relentless bureaucracy the brothers must appease; and the authentic, unmistakable John Lee Hooker, who gives the film an even deeper immersion into the roots of the blues, playing on a Chicago street. Every cameo is not a mere exercise in style, but a piece that enriches the mosaic of this incredibly dense universe, lending it further authenticity and charm.

Landis, with his bold vision and impeccable direction, is credited with shaping not only a film, but a lasting cultural icon: the men in black, with their dark suits, fedora hats, and sunglasses that conceal all emotion, save for a perennial, ironic imperturbability. They will impress themselves upon everyone's imagination with their eccentric obsessions, their irreverent manner, and that impossible mission which, in the end, proves to be the most sacred of endeavors. The Blues Brothers are much more than two comedians; they are archetypes of the rebel with a cause, of the winning underdog, of the indomitable force of music and the human spirit that refuses to bend to conventions. They remain a beacon of comedic genius and a sonic monument, a work that, decades later, continues to 'shaking its tail feather' with undiminished energy.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...