The Holy Mountain

1973

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a director with an otherworldly, surreal, and mystifying vision. His art does not merely narrate, but rather officiates a rite, a shamanic session that aims to shake the viewer's soul from its deepest foundations. Jodorowsky, a multifaceted figure of Chilean origin, raised amidst the fertile effervescence of the Panico movement – which he co-founded with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor – has always conceived of cinema not as mere entertainment or escapism, but as a vehicle for the expansion of consciousness, a form of collective psychomagic therapy.

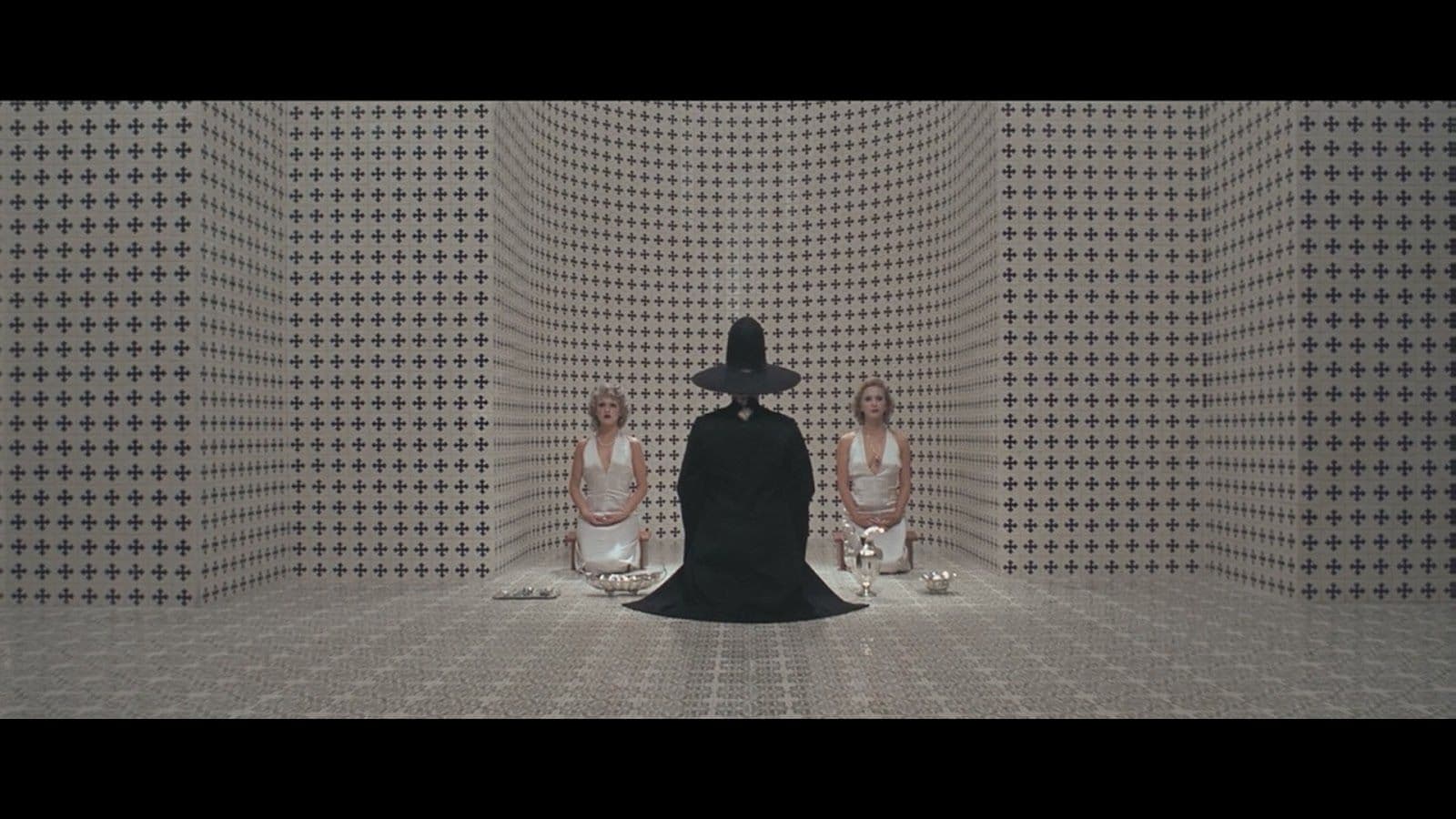

The Holy Mountain, in fact, is a film that strips away every certainty, eliminates every point of reference. It is not a linear narrative, but a dreamlike and disorienting ride through desecrated religious icons, grotesque pagan idols, and cheap miracles. Each sequence is a tableau vivant, a vivid and often jarring fresco that pushes beyond the boundaries of the usual, defying bourgeois logic and morality. The nude bodies, symbolic mutilations, surreal architectures, and saturated, almost hallucinogenic colors are not mere aesthetic whims, but instruments of a visual language that aims to bypass reason to communicate directly with the unconscious. Jodorowsky, in this regard, ideally connects with the surrealist cinema of Luis Buñuel, especially his most provocative works like The Exterminating Angel, while pushing the exploration of the subconscious into even more esoteric and spiritual territories, perhaps recalling the visionary freedom of a Fellini but with a far more declared transformative purpose. The film, imbued with the psychedelic aesthetic and transcendental aspirations of the 1970s counterculture, stands as a monument to rebellious and profoundly philosophical cinema.

At the heart of this epic, nine of the most powerful men on Earth, embodying cardinal vices and archetypes of worldly power – the bloodthirsty general, the arms magnate, the doll maker, the lady of beauty – embark on a quest for the Holy Mountain, where the source of Immortality is hidden. Each of them is a living allegory of spiritual failure masked by material success, an exaggerated caricature of the fixations and perversions of a Western society obsessed with consumption and appearance. Theirs is a search for immortality understood in the crudest and most material sense, an egoic prolongation of their earthly power, which will be systematically dismantled.

They will be guided by a sort of wandering messiah, an alchemist with enigmatic powers, played by Jodorowsky himself, who leads them through mystical trials and secrets to overcome to reach their goal. This master, a true cinematic demiurge, imposes upon his disciples not only an exhausting physical journey through hallucinatory landscapes and bizarre encounters, but an initiatory path that progressively strips them of their worldly identities, material possessions, and inner certainties. The entire process is a metaphor for the alchemical work: the nigredo (putrefaction), the albedo (purification), the citrinitas (solution), and the rubedo (perfection), which do not concern the transformation of base metals into gold, but the transmutation of the crude ego into pure consciousness. Jodorowsky applied these same transformation methodologies to his actors as well, subjecting them to diets, meditations, and spiritual exercises to make them "be" their characters, not just portray them.

Along the way, they will realize that true immortality does not reside in a physical elixir or a geographical location, but consists of (re)discovering their true self, stripped of all social trappings and purged of all human constraints. It is a journey of necessary disillusionment, a cathartic process through which the individual must dismantle their egoic superstructures to reveal their authentic essence. This theme of inner quest and liberation from the chains of materialism resonated deeply with the demands of the 1970s counterculture, for which The Holy Mountain, partly funded by John Lennon and Yoko Ono (who were ecstatic about the preceding El Topo), became a true cinematic and spiritual manifesto, albeit a niche one.

The film contains numerous references to the Kabbalah, the Zodiac, the Tarot (on which Jodorowsky has written several books), and naturally, Alchemy. These are not mere scholarly references, but conceptual pillars that structure the entire narrative and visual symbolism. Jodorowsky, as a diligent scholar and practitioner of the Tarot of Marseille – whose symbolism he has explored in numerous books and seminars, even overseeing its restoration – uses them as an esoteric map of the human soul, with characters sometimes embodying the archetypes of the Major Arcana. Likewise, Alchemy is not just a theme, but the operative principle of the film: to transmute the raw material of existence, represented by the protagonists' weaknesses and illusions, into spiritual gold, meaning awareness and enlightenment. Every scene is saturated with symbols, often layered, inviting the viewer to an active, almost meditative decoding, transcending mere passive reception.

A splendid work where reality often agonizes, giving the impression of a constant disorientation, of being continuously challenged by the narrator through the creation of parodic parables, in an infinite swirl of subconscious states. The biting satire against institutionalized religion and spiritual consumerism is sharp: we witness the mass production of religious idols, the crucifixion of a Christ-tourist taking photos, gurus dispensing wisdom for a fee. Everything is reduced to merchandise, including the quest for transcendence, and Jodorowsky fiercely unmasks this commercialization of the sacred, staging a world in which every ideal has been emptied of meaning and transformed into a mere product to be consumed.

The culmination of this disorientation arrives in the finale, one of the most audacious and memorable sequences in cinema history. After an exhausting and revealing journey, when the disciples are finally ready to reach the summit of the Holy Mountain and receive the secret of immortality, the alchemist breaks the fourth wall. The camera pulls back, revealing the entire scene as a film set, complete with crew, lights, and Jodorowsky himself addressing the viewer directly. "It is not true that truth is hidden in a place or an object," he admonishes, "truth is what you make of it. The Holy Mountain is not what you believed." This meta-cinematic gesture is not a simple breaking of fiction, but the ultimate expression of the film's message: enlightenment is not a passive destiny or an external revelation, but an active understanding and an inner construction. The film itself, like the protagonists' journey, becomes a mere tool to induce transformation in the viewer, a catalyst for their own personal "Holy Mountain." It is a long daydream that dissolves into the realization that the true journey, the only true quest, is within us, and that the canvas of cinema, however fascinating, is merely a means to illuminate the path.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...