The Incredible Shrinking Man

1957

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A small gem, indeed, a true rough diamond that in the hands of a skilled craftsman like Jack Arnold was transformed into a jewel of rare quality, shining brightly in the often crude and sensationalistic pantheon of 1950s science fiction. In a decade dominated by atomic paranoia and anti-communist hysteria, where UFOs and giant creatures proliferated on the big screens like radioactive mushrooms – a reflection of the anxieties of an America poised between economic boom and nuclear terror – The Incredible Shrinking Man (alas, that Italian title!), while stemming from the same fermenting fears, distinguished itself with a thematic depth and narrative sophistication that elevated it well above average, almost anticipating the philosophical turns the genre would embrace decades later.

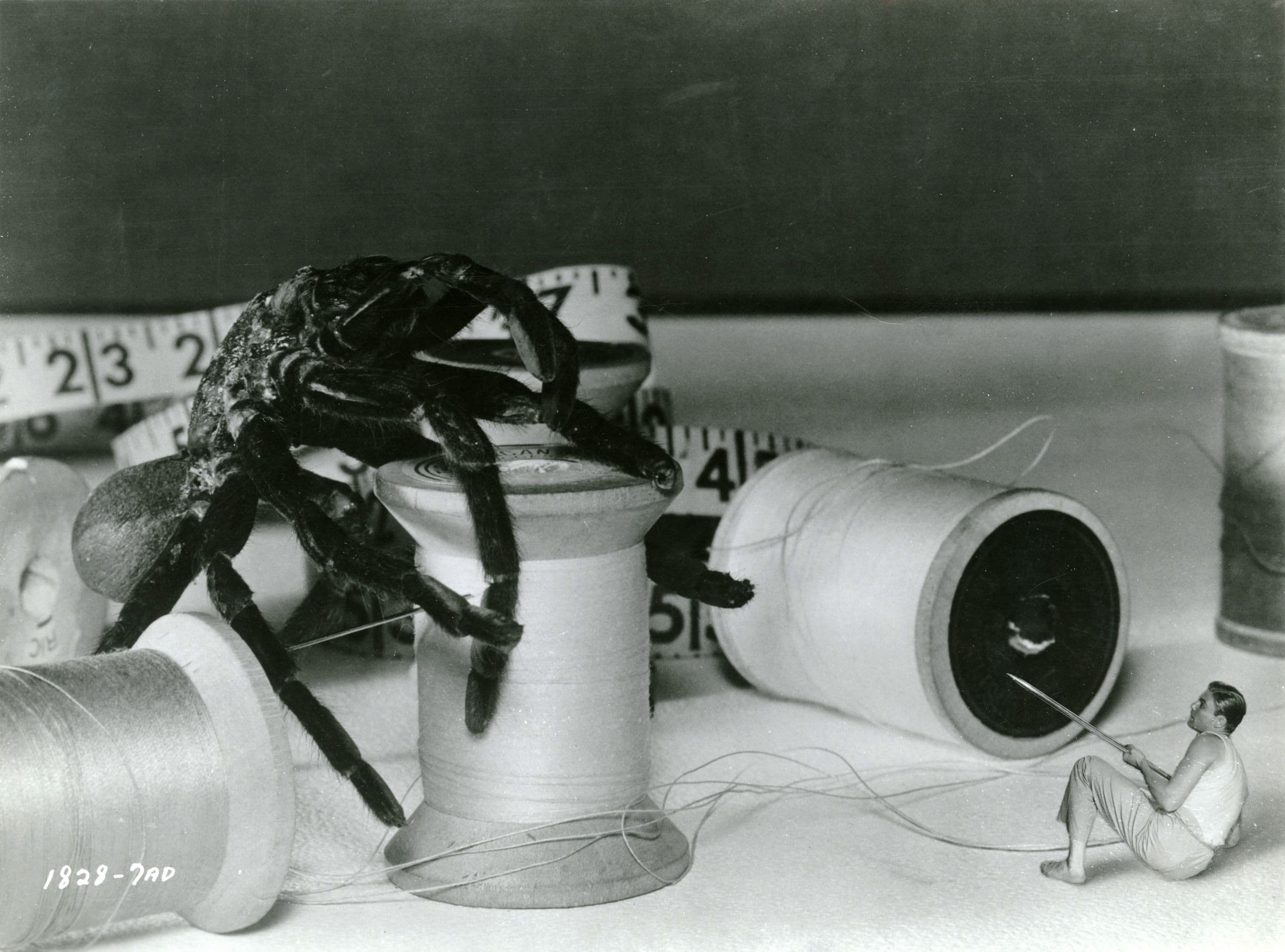

Produced with a budget that today we would consider negligible for special effects, but which at the time was managed with the ingenuity typical of Hollywood's golden age, the film was elevated by an intense and compelling screenplay, a true tour de force of psychological suspense and existential reflection. It was not a mere adaptation, but an almost perfect embodiment of Richard Matheson's genius, who from his own novel, The Shrinking Man (1956), distilled a cinematic work that retained the original text's disquiet and lucid despair. Matheson, an undisputed master of fantasy and psychological horror – one only needs to recall I Am Legend, Duel, or his memorable contributions to the television series The Twilight Zone – imbued the story with a sense of inevitability and a merciless analysis of human fragility, of its insignificance in the face of the unknown. To this solid foundation was added the creative and shrewd direction of Jack Arnold, a visionary craftsman capable of elevating the B-movie to an art form, as already demonstrated with Creature from the Black Lagoon and It Came from Outer Space. Arnold knew how to surprise the viewer with innovative technical solutions – the masterful use of forced perspective, the construction of oversized sets that transformed common objects into imposing mountains, and the integration of cutting-edge visual effects for the era like matte painting and rear projection – succeeding in making tangible the idea of the overwhelming immensity of the perceptible world, which progressively manifests itself around the protagonist. It was not just a visual trick, but a vehicle for anxiety, an expression of ontological terror that lurks in the loss of every point of reference.

Scott Carey, an ordinary man, a symbol of the reassuring American middle-class normality of the 1950s, is struck by a mysterious radioactive cloud, perhaps the long and invisible shadow of the Cold War and nuclear experiments that loomed over the collective consciousness, transforming atomic fear from an external threat into internal corrosion. From that moment, his irreversible descent begins, a physical and psychological ordeal: he gradually starts losing weight and stature, an inexorable process that tears him away from his world, his role, his very definition of 'human being'.

The horizon of his world does not shrink, paradoxically, but expands immeasurably, transforming domestic familiarity into a hostile and incomprehensible expanse. Soon, the house, a sanctuary of bourgeois everyday life, becomes a true survival field, a primordial arena where every object, every element, assumes menacing and titanic proportions. The struggle with the spider, one of the film's most iconic and claustrophobic sequences, is not a mere suspense device; it is the perfect metaphor for modern man's regression, reduced to his barest and most vulnerable essence, forced to confront a nature no longer dominated, but wild and indifferent, even in his own living room. It is the primacy of biology over civilization, a reminder of the most ruthless Darwinism, but also an allegory of cosmic solitude and the absurd in the face of a predetermined destiny.

Splendid, indeed, indispensable for their emotional and psychological resonance, are some intermediate scenes that punctuate the dramatic process of “de-growth”. Impotence, both physical and metaphorical, is a common thread that runs through the narrative with an unexpected sensitivity for the genre: the sexual failure with his wife, emblematic of the progressive erosion of his masculinity and his role as head of the family, is a moment of raw and disarming truth, which demolishes the image of the omnipotent man. The relationship, almost a bittersweet illusionary parenthesis, with the female dwarf, a kindred spirit in her deviation from social norms, is a desperate attempt to cling to a glimmer of normality and human connection, also destined to dissolve with the inexorable advance of his fate. These moments are not mere interludes, but narrative pillars that show the devastating impact of the transformation on Scott's identity, relationships, and psyche, painting a picture of ever-deepening isolation, an alienation reminiscent of the Kafkaesque individual, trapped in an incomprehensible metamorphosis, or the Camusian Sisyphus who continues to push his boulder towards the inevitable fall.

A work that is not lacking in speculative insights; indeed, it is imbued with them to the core, elevating itself to a philosophical parable. Human impotence in the face of progress, or rather, in the face of its uncontrollable and unexpected consequences, is just the tip of the iceberg. The film goes far beyond a simple warning about runaway science, touching deep existential chords. It is an exploration of the fragility of identity: what remains of a man when his body, his environment, his perception of reality are subverted to the point of rendering him a living paradox? The deafening silence of the cosmos, the indifference of physical laws, the vanity of social conventions in the face of the inevitability of dissolution – these are Scott Carey's true antagonists. The protagonist's inner narration, at times almost Beckettian in its lucid despair and its final acceptance of an inconceivable fate, transforms his odyssey into a meditation on transcendence and man's place in the universe. From insignificant dimensions, Scott arrives at an almost mystical understanding of his new, infinitesimally small, yet in some way grandiose, place. His disappearance is not a defeat, but a dissolution into the infinite, a reunification with the primordial atom, an acceptance of the fact that his existence is part of a much vaster cycle indifferent to meager human perceptions, an enlightenment that nullifies fear and culminates in a lyrical, almost poetic, transcendence. It is Stoic philosophy meeting quantum physics, with surprisingly lyrical and profound results, which still resonate today for their intellectual audacity.

A film, unfortunately, marred by an Italian title – Radiazioni BX Distruzione Uomo – worthy of the most unrefined and superficial B-movie, a crude label that blatantly betrays the depth and elegance of a work which, instead, deserves to be counted among the masterpieces of science fiction of all time. A marketing error that for decades perhaps prevented many from approaching a film that is in reality a moving and cerebral journey into the unknown, an intimate and universal epic that continues to resonate powerfully in its examination of identity, perception, and man's place in an ever-expanding cosmos, or, in Scott Carey's case, an ever-miniaturizing one. A classic that, beyond its tricks, reveals the rawest and most fascinating truth: we are not at the center of anything, but part of everything, infinitesimal yet indispensable, in a universe whose grandeur is only limited by our capacity to perceive it.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...