The Last Laugh

1924

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Murnau, in a turnabout as audacious as it was brilliant, abandons the Gothic stylings and dark atmospheres of masterpieces like Nosferatu to immerse himself in a crackling realism, in which every frame is dynamic iconography of a narrative subservient to images, expressions, and people's faces. Yet, in some way, he goes beyond mere veristic realism, penetrating the protagonist's soul and representing his emotions in a visceral and intense manner. It is no longer just about depicting external reality, but about making its internal resonance tangible, an approach that fully inscribes him into the Kammerspielfilm genre, the German "chamber film," devoted to intimate psychological inquiry and drama focused on a few characters and settings. The German director, through this story of ordinary downfall, looks at his Germany and draws a merciless social picture, fiercely criticizing its growing individualism, obsession with status, and the massification of ideas, a true mirror of the neuroses of the Weimar Republic, torn between industrial progress and adherence to rigid social hierarchies. The story, not by chance, is inspired by Gogol's tale "The Overcoat," a literary archetype of the man annihilated by bureaucracy and social indifference, and entrusted to the screenplay by Carl Mayer. The latter, a key figure in German cinematic Expressionism and already a collaborator of Murnau's for The Last Night, transposes its surreal atmospheres and bitter fatalism, fitting them with almost surgical clarity into post-war German reality, imbuing the story with a universal resonance while simultaneously grounding it specifically in its own time.

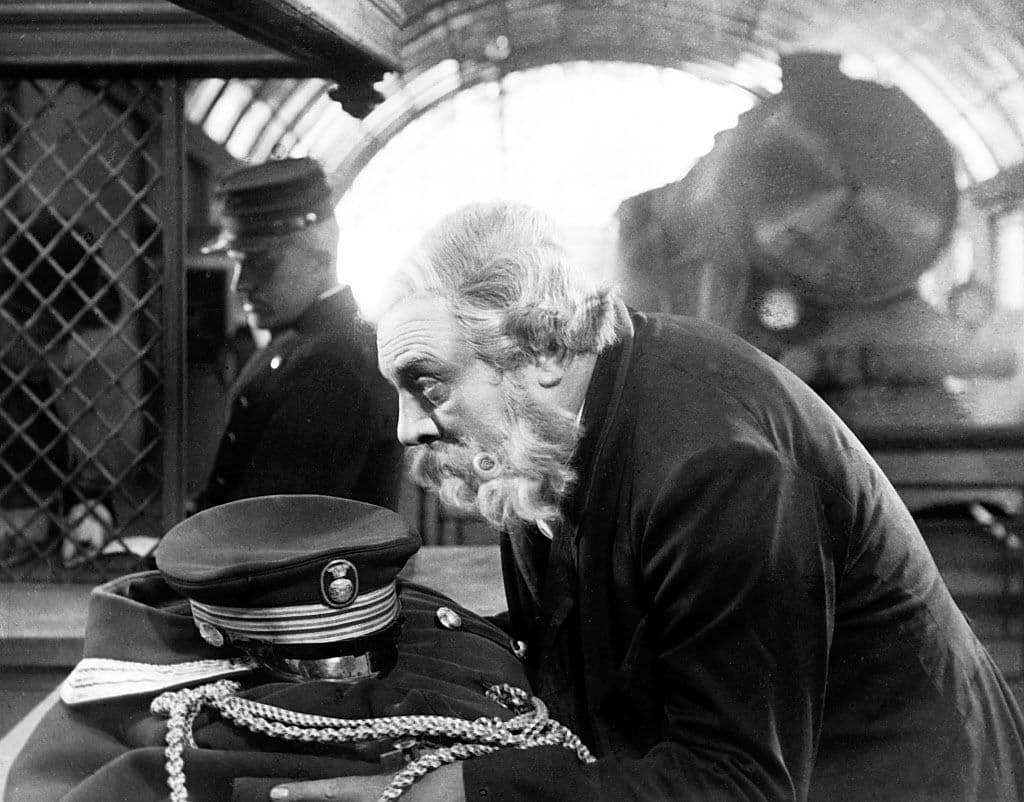

An hotel porter, majestic in his impeccable uniform, reigns over a world of bellhops, taxi drivers, and delivery boys, a social microcosm where hierarchy is dictated by uniforms and functions. Murnau tells his tragic parable: the story of a man proud of his uniform, a symbol of his social status, a bulwark against anonymity, and a means to elevate himself above the rabble surrounding him. When he is demoted to cleaning bathrooms, thus losing every vestige of his dignity and his very social "skin," his world collapses around him. The loss of the uniform, which for him represented far more than a mere garment—it was his shield, his identity, and his reason for being within the established order—deprives him of any foothold and relegates him to the margins of an unforgiving society. Contrary to a traditional use of flashbacks, which would have broken the narrative flow, the film explores his inner world not through didactic recollections of the past, but with a revolutionary use of the camera. Murnau deploys his celebrated "entfesselte Kamera" (unfettered camera) here, which moves with unprecedented freedom, following the protagonist in confined spaces, ascending and descending stairs, even penetrating his mind in dreamlike and hallucinatory sequences that reflect his turmoil, his shame, his psychological downfall. This technical innovation allows the director to express the character's subjectivity without the aid of intertitles, making his emotions palpable and his despair contagious. The protagonist's fall is recounted with a merciless magnifying glass, underscoring the often cruel importance society attaches to appearance and social status, elements that can define or annihilate the individual. The film concludes with a scene that, despite its poignant and bitter immediacy, does not fail to generate debate. The famous fake and ironic "happy ending," often interpreted as a studio imposition to soften the story's dramatic intensity, ends up transforming into a further mockery, a "last laugh" not of the protagonist but of fate itself or of cosmic irony, leaving the viewer with a deep sense of melancholy and disillusionment, made even more bitter by that forced, almost sarcastic, final redemption.

Murnau inherits from Gogol the theme of social alienation and humiliation suffered by an individual on the margins of society, but he amplifies and enriches it with visual and symbolic elements characteristic of German Expressionism. The film's dark and oppressive atmosphere, the almost imperceptible but pervasive distortion of figures and spaces—through skillful use of set designs, lights, and shadows, which tighten around the protagonist like a noose—are all elements that recall the Gogolian poetics of the grotesque and existential unease, but which are reinterpreted and reinvented through the lens of Expressionist aesthetics. Here, urban spaces are not mere backdrops, but actual characters that interact with the human drama. The city becomes a tentacular entity, with its imposing buildings and crowded streets that amplify the individual's alienation and solitude, swallowed by his own environment. Ultimately, The Last Laugh is not a mere cinematic transposition of "The Overcoat," but an autonomous work that dialogues profoundly and complexly with the original text, offering the public a new and original interpretation of a universal theme: the fragility of identity in a world that commodifies human dignity. With this film, Murnau stages the obliteration of the individual by forces overwhelming and unreachable to him—social judgment, impersonal bureaucracy, the crushing weight of conventions—a narrative articulation that would later be taken up by numerous other directors, from Chaplin to Kafka, from Fritz Lang in M to Italian Neorealist cinema which also investigated the fate of the humble, even influencing dystopian and allegorical works like Terry Gilliam's Brazil. Murnau's work, therefore, is not limited to being a masterpiece of its time, but stands as an authentic archetype of cinematic narration about the common man against the social Leviathan, making it a beacon for entire generations of filmmakers.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...