The Man Who Wasn't There

2001

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

After their splendid early work Miller's Crossing, the Coen brothers return to noir, and they do so in their own way: with a refined style strongly inspired by the fertile 1950s, a decade that, beneath its veneer of prosperity and conformity, already harbored the seeds of a profound existential unease. Their return is not merely nostalgic, but an operation of deconstruction and reinterpretation of a genre that has always captivated their aesthetic.

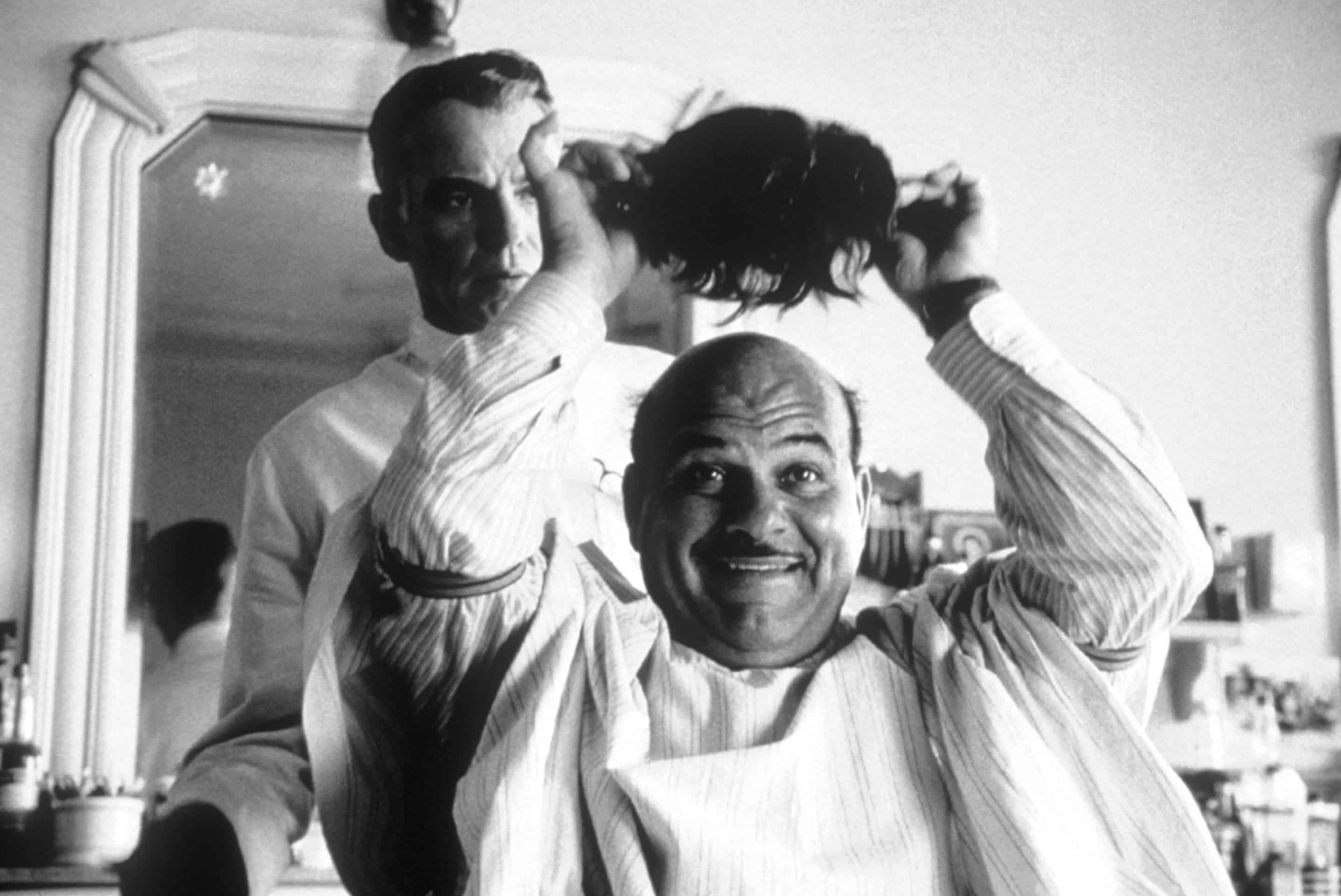

The result is a polished work, but with a sheen that evokes the sickly luster of vintage films, featuring allusions and homages to the hard-boiled genre that go far beyond mere stylistic surface. It is a true dialogue with giants of the caliber of James M. Cain or Raymond Chandler, but filtered through the Coens' idiosyncratic and deeply pessimistic lens. The breathtaking cinematography, crafted by master Roger Deakins – here probably at the apex of his monochromatic art – elevates every shot to an auteur's painting, lending the film an almost pictorial dimension, where light and shadow are not merely visual elements but true silent characters, narrating inner desolation and the inexorability of fate.

The use of black and white, therefore, is but a natural complement to this artistic project, a structural pillar that transcends mere aesthetic choice to become a stylistic and conceptual signature. It imbues the narrative fabric with disquiet and beauty, transporting the viewer into a suspended, almost dreamlike atmosphere, where morality becomes ambiguous and truth hides in a labyrinth of chiaroscuro. The infinite and nuanced shades of grey mirror the scale of moral grays that defines the existence of Ed Crane, protagonist of this tragic and bizarre epic. It is a black and white that takes up the expressionist lesson, borrowed from classic 1940s noir, but transfigures it, purifies it, imparting a luminosity that, rather than reassuring, sharpens the sense of alienation.

The story is that of Ed Crane, a sad barber with a perennial suspicion of being betrayed by his wife, Doris, portrayed by Frances McDormand, who imbues the character with a desperate ordinariness. Ed embodies the archetype of the Coenian anti-hero, a passive, almost transparent man who seems to slip through life without leaving a trace. His apathy is not indolence, but a form of existential defense, the response of an emptied soul to a world that seems intrinsically absurd to him. This "man who wasn't there" moves in a world that ignores him or overwhelms him, and his lack of initiative makes him not so much an agent of his own destiny as a pawn in a cosmic game whose outcome is already written.

To escape these bleak thoughts, or perhaps to confirm his own invisibility even to himself, he will embark on a reckless initiative, but to do so, he will extort a sum of money from his wife's lover, a businessman with a mellifluous air and an elastic conscience. The spiral of events that follows is a classic example of the Coens' narrative mechanics: a single, albeit serious, deviation from the norm triggers an unstoppable chain reaction. Ed will kill the lover in a fit of rage, a moment of violence that, far from being cathartic, plunges him into an abyss of even darker consequences. A vortex of grim consequences will forever overturn his life, plunging him into an odyssey of misunderstandings, deceptions, and plot twists that seem orchestrated by a mocking fate. It is a bleak and disturbing film, with a watermark of bitter cynicism that envelops every narrative turn, an unsettling danse macabre on the stage of human existence. The narrative proceeds with an almost mathematical linearity, yet permeated by surreal deviations, such as the inexplicable, and brilliantly Coenian, incursion of a hypothetical alien invasion that turns out to be a hoax, but which adds an additional layer of absurdity and paranoia to Ed's already fragile reality. This bizarre subplot, seemingly unrelated, actually reinforces the film's central theme: the desperate search for meaning in a universe that refuses to provide it.

Ed's rarefied disenchantment as he faces the electric chair makes the final sequence a "cult scene" to be archived and preserved in the pantheon of most memorable cinematic conclusions. The man walks down a long corridor escorted by two police officers; his face is relaxed, almost serene, a mask of resignation that is not surrender, but almost transcendence. Billy Bob Thornton's performance here reaches its peak, conveying a calm that is deeper than despair, an acceptance of his own intrinsic non-existence. The corridor, a symbol of passage and inevitability, is lit by wall lamps that cast a skewed and symmetrical light, creating a play of perspectives that seems to dilate time and space. Ed walks through it, reflecting on his life, and wondering, with an inner voice that is the quintessence of his detachment, if he should regret anything. His inner monologue is an echo of many noir anti-heroes, but with a peculiar note of cosmic fatalism that makes it unique.

A door suddenly opens, revealing a blindingly white room: everything is white, the boundaries between walls, ceiling, and floor are indistinguishable. It is a timeless, almost platonic space, where matter dissolves and nothingness manifests in its purest and most blinding form. It is a 'non-place' that evokes both the idea of an aseptic afterlife and that of a definitive annihilation, a void that reflects Ed's very soul. A blinding beam, almost divine in its intensity, is interrupted only by the grim electric chair, in the center, awaiting its guest. There is no theatrical drama, no pleading, only cold, geometric inevitability. This final image is a stroke of genius: the almost mystical whiteness of a space that precedes judgment or oblivion, which elevates death to an almost transcendental experience, yet devoid of all consolation. It is the perfect ending for a parable about the man who wasn't there, and who, in the end, disappears into a final, dazzling absence. A hymn to absurdity and nihilism that only the Coens could conceive with such elegance and visual power.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...