The Mission

1986

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Written and with screenplay by Robert Bolt, based on an original story, the film is set in South America in 1750, in the rainforest located above the Iguazu Falls, in a portion of land that today is divided into three states: Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. The historical context is not a mere picturesque backdrop, but a silent and pervasive character: we are on the eve of the Treaty of Madrid (1750), an infamous agreement between the crowns of Spain and Portugal that redrew the South American colonial borders according to the principle of "uti possidetis", completely disregarding human realities and fragile indigenous communities, including the celebrated Jesuit reductions. These latter represented a unique social and spiritual experiment, an attempt to create a model of society based on equality, self-governance, and the protection of the Guarani Indios from the rapacity of the Portuguese bandeirantes and the Spanish encomenderos.

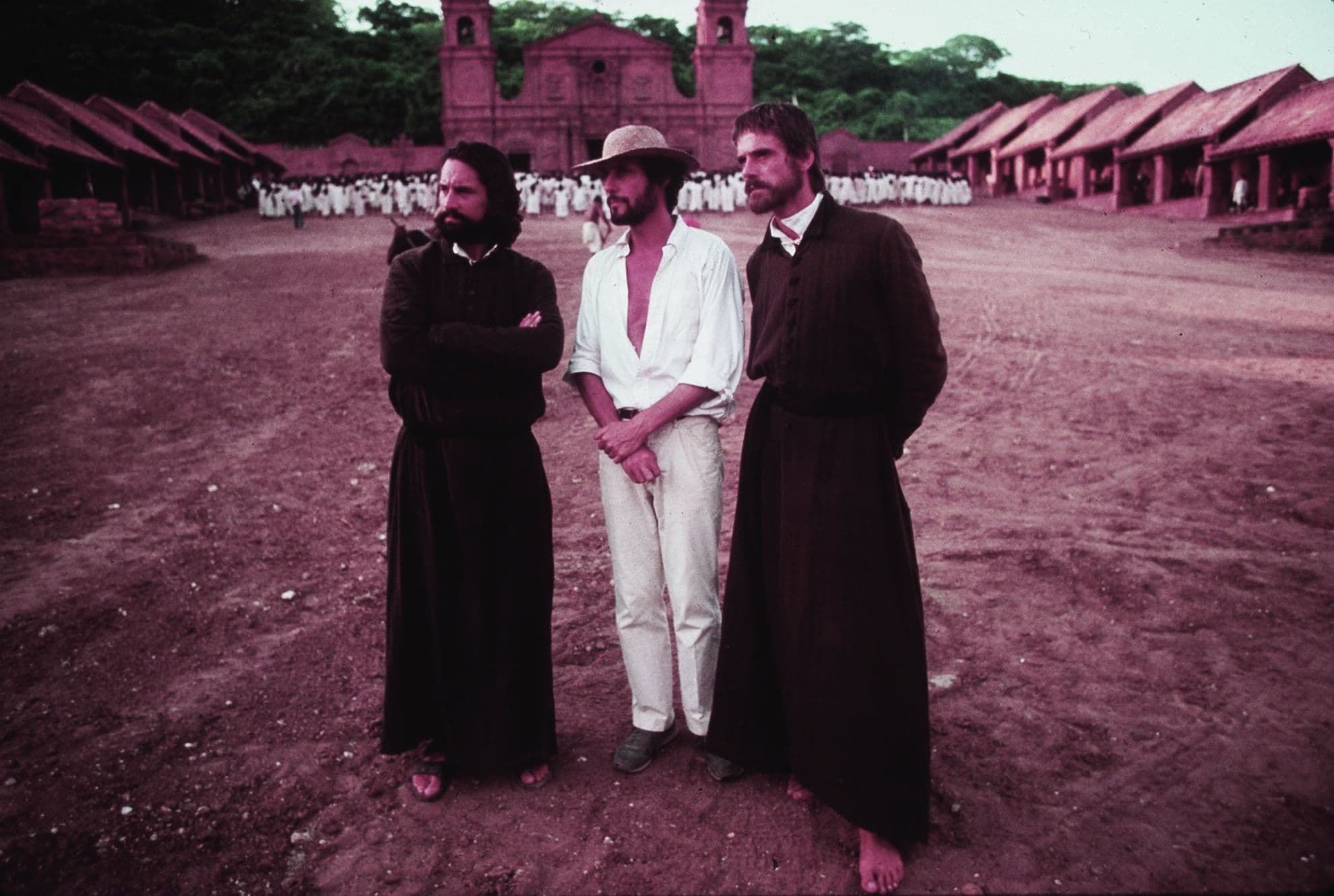

The film follows the events of a Jesuit missionary, Father Gabriel (an archetypal figure of spiritual dedication), who ventures into that wild land to make contact with the Indios and attempt to convert them to Christianity. His approach is diametrically different from all others who had attempted before him, from any form of coercive proselytism or colonial violence. Gabriel plays his oboe, enchanting the Indios with the melody, who welcome him into their village, allowing him to build a church, the focal point of the new mission. This opening scene is already a programmatic manifesto: music, a universal and pure language, stands as a bridge between cultures, a vehicle for a message of peace and mutual respect, in stark contrast to the weapons and subjugation that marked the history of conquest. The choice of the oboe, an instrument with a melancholic and spiritual voice, is not accidental: it symbolizes the fragility of an ideal of harmony destined to clash with the harsh reality of power.

Right from the opening scenes, the elements that would define the film's success are introduced, elevating it to a sublime visual and sonic epic: the pristine and lush nature, brought to life by Chris Menges' splendid cinematography (already a collaborator of Joffé in the excellent "The Killing Fields" of 1984), cinematography that does not merely document, but elevates the landscape to a sacred entity, a refuge of primordial purity. The twilight light filtering through the dense canopy, the vivid textures of the vegetation, the almost terrifying majesty of the waterfalls: everything contributes to creating a sense of grandeur and vulnerability, a paradisiacal Eden on the verge of being profaned. It is an ode to wild beauty, a warning about its intrinsic fragility in the face of the blind logic of profit and conquest. This vision is blended with Ennio Morricone's hypnotic score, featuring the theme "Gabriel’s Oboe", which becomes a kind of cathartic mantra within the narrative and indeed one of the most renowned and beloved cinematic melodies of all time. It is not merely background music; it is a polyphonic chorus that expresses pain, hope, spirituality, and impending tragedy. Morricone, with his mastery, interweaves sacred sonorities, melodic themes that evoke lost purity, and the dramatic urgency of events, culminating in an orchestra that amplifies every emotion, every sacrifice. His ability to make music "speak", to render it a driving force and a narrative vehicle, reaches unparalleled heights here, making the oboe theme almost a character in itself, a vibrant soul that permeates the film. Completing this triumvirate of artistic excellences is the superb acting performance by Jeremy Irons, in a state of grace, whose austerity and quiet determination embody the unshakeable strength of faith and the tragic awareness of the inevitable.

In parallel, a second character is introduced: the Spaniard Rodrigo Mendoza (Robert De Niro), a slaver and man-at-arms who, having committed a terrible crime – the murder of his brother out of jealousy and passion – yearns for a seemingly impossible redemption. He atones for his guilt by physically carrying its burden through the forest, a sack containing his heavy armor.

The central scene of the film is undoubtedly this modern-day Sisyphus, struggling through nature's obstacles, under the initially scornful gaze of the Indios and then the compassionate gaze of Father Gabriel, dragging the weight of his armor, a tangible symbol of a life of violence, sin, and oppression. It is a sequence of extraordinary intensity, a true secular via crucis and, at the same time, profoundly spiritual, reminding us of the labors of biblical and mythological figures, yet situated within a dimension of personal redemption. Once that tremendous metallic weight sinks into the waters of Iguazu – a ritual baptism in the pure and violent waters of the waterfall, a visceral and liberating catharsis – Rodrigo will finally be free from his old life as a man-at-arms and will be able to join the missionaries as a fervent servant of God, demonstrating through his journey the possibility of a radical transformation and a rediscovered faith. His is a repentance expressed not only in prayer, but in action, dedication, and ultimately sacrifice.

Meanwhile in Europe, the Spanish commit to ceding part of their South American possessions to the crown of Portugal, and Father Gabriel's mission is among these. A tough negotiation will begin between the Church, Spain, and Portugal for the fate of the mission, a cold diplomatic dance in which the lives and culture of thousands of people are reduced to mere pawns on a geopolitical chessboard. The Church, divided between the protection of the reductions and the political and economic pressures from the Roman Curia, finds itself in an impossible position of compromise, revealing its internal fragilities and hypocrisies.

As often happens, the purity of the Indios will be trampled upon by the overbearance of European colonialism. The tragedy is inevitable, a Greek drama disguised as a historical epic, where the highest virtues clash with the lowest of covetousness. In Joffé's vision, human passions, their thirst for power and wealth, encounter and brutalize God's purity through the unspoiled existence of indigenous populations. His position is clear, and his criticism of the fierce partitioning of South American lands is all too evident, a desperate cry against the destruction of an earthly and spiritual paradise. "The Mission" is not just a historical film; it is a powerful allegory about the collision between idealism and political realism, between faith and raison d'état, leaving the viewer with a deep, burning melancholy for what has been lost and for the countless times history has repeated the same painful lesson of overbearance and destruction. It is a work that, decades later, continues to resonate for its aesthetic beauty and the timelessness of its moral warning.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...