The Naked Island

1960

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

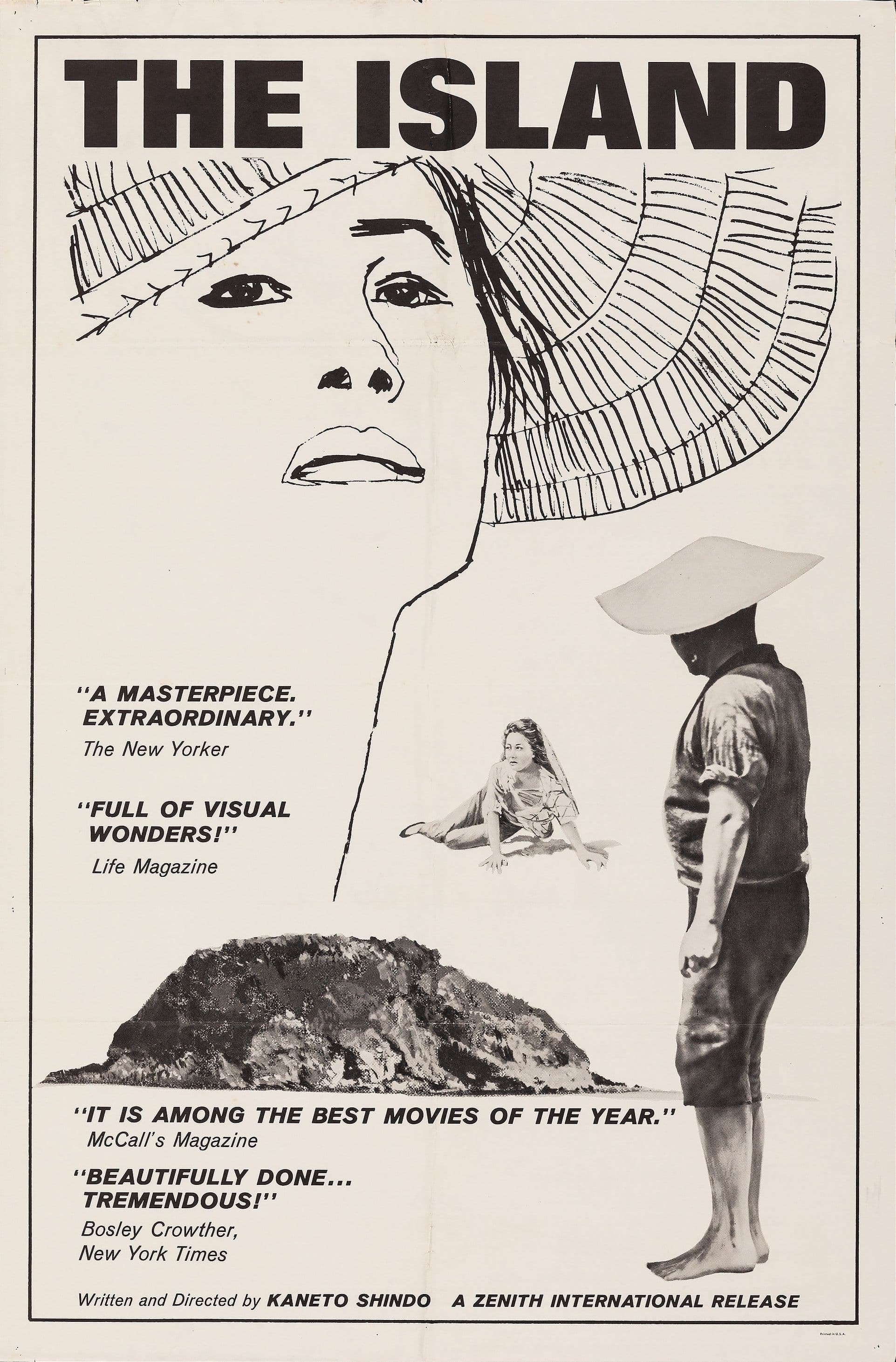

Sometimes we are confronted with works that strike us with the sheer power of images, a kind of inescapable iconic energy capable of overwhelming and captivating us. Kaneto Shindô's film is perhaps the clearest example of this. A work that needs no words, it stands like a monolith against the horizon and grips us with its imposing dark mass. This supremacy of image over word, an almost radical stylistic hallmark, elevates the film to a form of pure cinema, perhaps indebted to the glories of the silent era or the bolder explorations of the avant-garde, where meaning springs directly from visual composition and the rhythm of gestures. The Naked Island, or rather Hadaka no Shima in its original title, is indeed an almost anomalous work in the sound cinema landscape, an essay in minimalist yet monumental aesthetics. Its 'nakedness' refers not only to the harshness of the place, but also to its bare narrative essence, the emotional nudity of its protagonists, the raw and unmediated truth it reverberates. From the very first striking images that unfold, one experiences a sense of suspension, an aesthetic estrangement that projects us into this microcosm where Kaneto Shindo moves his characters.

A woman laboriously ascends a slope of a small island, carrying a yoke with two enormous buckets of water. The effort expended is so palpable that it becomes a physical entity in the foreground. Hers is a daily Calvary, a reiteration of titanic efforts that elevate the mundane act of fetching water to a sacred ritual, an existential metaphor. Not coincidentally, the film, despite being sound-engineered with almost maniacal precision that highlights every creak and every breathless gasp, almost entirely foregoes dialogue. Words would be superfluous, redundant, even offensive in the face of the eloquence of the bent body, tense muscles, and sweat beading on the forehead. This stylistic choice, far from being a limitation, becomes Shindô's propulsive force, compelling us to read the souls of his characters through action, tacit expression, and the relentless wear of toil. Camus's Sisyphus would find in this woman a cinematic alter ego, condemned to an eternal ascent, yet possessing a silent dignity that transcends pure suffering. Following her Calvary, the director reconstructs the harsh life of a four-person Japanese family (Father, Mother, and two children) living on this Pacific islet where, defying an atavistic Nature, they struggle to survive. This glimpse of life on an uninhabited rock in the Seto Inland Sea, in a post-war Japan seeking its rebirth also through a return to the most basic forms of subsistence, becomes a universal fresco on the human condition. Nature, here, is not a stepmother in the romantic sense of the term, but a primordial and indifferent force, to which humanity adapts with an almost desperate resilience. The terraces painstakingly carved into the rock, the winding paths sculpted by time and effort, the boats cutting through the metallic blue of the sea, are not merely scene details, but silent testimonies to a stubborn struggle for bare survival, a mute drama unfolding between the infinite vastness of the sky and the implacable harshness of the earth. Due to the lack of water, to irrigate crops cultivated on steep terraces overlooking the sea, they are forced to shuttle by small boat to a nearby island. Every day they transport water and goods they barter with the produce of the land, taking their two children to study on the nearby island.

But a terrible event seems to tear through this life of hardship and sacrifice: the eldest son falls ill and dies due to lack of adequate care. The wife, a key character in the story, experiences a surge of rebellion and seems to cry out her bitter frustration against her husband who led her to that remote, God-forsaken place, a desperate uprising against a harsh Nature, against the cruelty of a mocking and cynical Fate. The wife's silent cry, her shaking her husband with a sudden, almost atavistic violence, is the most lacerating breaking point of the entire film. It is not an audible scream, but a surge of rage and pain that manifests in disjointed gestures, in a physical explosion that shatters the rigidity, the austere composure maintained until then. It is the culmination of an accumulation of suffering, an emotional point of no return that, for a fleeting moment, threatens to collapse the entire fragile balance of their existence. Yet, precisely in this apparent rebellion, the tragic grandeur of the film manifests: the inevitability of fate allows no deviations. Her rebellion, however, is nothing more than an infinitesimal discord, a microscopic subversion that dissolves into the infinity of the Ocean, into the receding marine Blue intertwined with a cobalt Sky. That surge of rebellion, potent as it is in its visual expression and emotional impact, resolves itself into a return to order, to the very routine it seemed to have shattered. Then everything resumes, immutable, eternal, inescapable: without a shadow of hope, of pale redemption. The hand that begins to hoe the earth again, the body that resumes the incessant rhythm of toil, are the seal of a resignation that is not weakness, but the highest form of human resilience in the face of the implacable and cyclical dance of life and death. It is a bitter fatalism, certainly, but imbued with indomitable dignity.

The intimate realism of this film is wonderful in depicting the daily life of the family in its stubborn cultivation methods, in its daily chores made of self-built tools, ingenious water storage, a continuous and laborious compromise between Soul and Nature. This 'intimate realism' is never documentary in the cold sense of the term, but is imbued with a profound and moving humanity. Shindô's direction is of an almost choreographic precision; every movement, every gesture, from food preparation to the meticulous irrigation of plants, is orchestrated with a meticulousness that elevates the mundane to the sublime. Kiyomi Kuroda's black and white cinematography, with its sharp contrasts and its ability to capture the texture of the rock, the fluidity of water, and the power of the landscape, contributes to creating a timeless, almost mythical atmosphere. The almost total absence of non-diegetic music amplifies this effect, allowing ambient sounds – the rustling of the wind, the lapping of waves, the clanging of buckets – to build the soundtrack of this elemental existence. With this work, Shindo proves to be not only one of the greatest and most prolific screenwriters in Japanese Cinema (his collaboration with Mizoguchi became legendary), but a complete and sensitive man of Cinema, a great artist who managed to carve out a prominent place in the history of Japanese cinematography. Shindô, a complex and prolific figure in Japanese cinema, capable of ranging from the brutal realism of this work to the almost horror and supernatural tones of subsequent masterpieces like Onibaba or Kuroneko, reveals himself here in his purest and most radical aspect. The Naked Island is not just a film about survival, but a universal meditation on toil, loss, and the stubborn continuity of life, a masterpiece that remains etched in memory for its ability to speak to the soul without uttering a single word, and to transcend its specific setting to touch deeply human and timeless chords.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...